Les administrateurs de sociétés doivent être beaucoup plus informés des conséquences que les fonds activistes peuvent avoir sur la conduite des entreprises publiques (cotées).

Il plane un air de mystère, et un certain mutisme, sur la nature des opérations et sur les objectifs poursuivis par les investisseurs activistes.

Pourtant, même si le phénomène est de plus en plus répandu, on constate un manque flagrant de formation des administrateurs de sociétés sur les types d’arrangements recherchés par les activistes.

Les pionniers de la recherche dans ce domaine, Lucian Bebchuk* et ses collègues, viennent de publier un billet sur le site de Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, qui fait la lumière sur le comportement des investisseurs activistes.

Que recherchent les activistes ? Ils veulent convaincre les directions et les conseils d’administration que leurs préconisations conduiront à une meilleure valorisation de l’entreprise.

Ils souhaitent tirer parti des faiblesses de certaines organisations dans le but premier de faire profiter leurs investissements, tout en améliorant la rentabilité des entreprises qui ont des problèmes de gouvernance, de leadership et de vision stratégique.

Quels sont les résultats de la recherche des auteurs eu égard aux motivations, à la nature des arrangements ainsi qu’à leurs conséquences ?

L’étude montre que les négociations sur les modifications organisationnelles souhaitées, reliées au renouvellement du leadership et à la remise en question des opérations, sont difficiles à convenir.

Les fonds activistes préfèrent de loin arriver à des ententes sur la composition du conseil d’administration susceptible de favoriser les changements escomptés.

L’étude indique que les modifications à la constitution du CA mènent souvent :

- au remplacement du PDG (CEO) ;

- à des paiements accrus aux actionnaires ;

- à une plus forte probabilité de vente ou de privatisation de l’entreprise.

Finalement, l’étude montre que les avantages obtenus par les actionnaires activistes ne se font pas au détriment des autres investisseurs. Également, le prix des actions est généralement à la hausse à la suite des négociations sur les arrangements.

Les auteurs dévoilent aussi les moyens utilisés par les fonds activistes pour arriver à leurs fins (« a look into the black box »).

Je suis personnellement convaincu que certaines conséquences non anticipées se produisent et que cette étude doit être mise en relation avec d’autres recherches, notamment celles du professeur Yvan Allaire**.

Afin de mettre en valeur de bonnes pratiques mises en places par des conseils d’administration des sociétés québécoises, le journal Les Affaires, en collaboration avec l’Institut des administrateurs de sociétés (IAS), le Collège des administrateurs de sociétés et l’Institut sur la gouvernance (IGOPP), a tenu le 1er avril dernier une Grande soirée de la gouvernance. Durant cette soirée, le professeur Yvan Allaire, président exécutif du conseil d’administration de l’IGOPP a dévoilé en primeur une étude sur l’enjeu des investisseurs activistes et leurs conséquences pour les conseils d’administration.

Conclusions préliminaires de cette étude :

(1) Les fonds de couverture activistes ne sont pas des « super‐cracks » de la finance, ni de la stratégie, ni des opérations, comme certains semblent le croire (et eux s’évertuent à le faire croire) ;

(2) Leurs recettes sont connues, convenues et prévisibles et ne comportent jamais (ou presque) de perspectives de croissance ;

(3) Leur succès provient surtout de la vente des entreprises ciblées (ou de « spin‐offs ») ;

(4) L’appui important qu’ils reçoivent des fonds institutionnels est surprenant et malencontreux ;

(5) La gouvernance fiduciaire pratiquée depuis Sarbanes‐Oxley et la perte de confiance dans les conseils qui en a résulté leur ouvre toute grande la porte des entreprises.

Bonne lecture. Vos commentaires sont les bienvenus.

Dancing with Activists

We recently released a study, entitled Dancing with Activists, that focuses on “settlement” agreements between activist hedge funds and target companies. Using a comprehensive hand-collected data set, we provide the first systematic analysis of the drivers, nature, and consequences of such settlement agreements.

Our study identifies the determinants of settlements, showing that settlements are more likely when the activist has a credible threat to win board seats in a proxy fight. We argue that, due to incomplete contracting, settlements can be expected to contract not directly on the operational or leadership changes that activists seek but rather on board composition changes that can facilitate operational and leadership changes down the road. Consistent with the incomplete contracting hypothesis, we document that settlements focus on boardroom changes and that such changes are subsequently followed by increases in CEO turnover, increased payout to shareholders, and higher likelihood of a sale or a going-private transaction.

We find no evidence to support concerns that settlements enable activists to extract significant rents at the expense of other investors by introducing directors not supported by other investors or by facilitating “greenmail.” Finally, we document that stock price reactions to settlement agreements are positive and that the positive reaction is higher for “high-impact” settlements. Our analysis provides a look into the “black box” of activist engagements and contributes to understanding how activism brings about changes in its targets.

Below is a more detailed account of the analysis and findings of our study.

In August 2013, Third Point, the hedge fund led by Daniel Loeb, disclosed a significant stake in the auction house Sotheby’s, criticized the company for its poor governance and its failure to take advantage of a booming market for luxury goods, and called for the ouster of the company’s CEO. Third Point launched a proxy fight for board representation and both sides prepared for a contested election at the company’s upcoming annual meeting. However, the day before the scheduled annual shareholder meeting, the company’s board of directors and the activist fund entered into a settlement agreement in which Sotheby’s agreed to appoint three of the Third Point director candidates and Third Point agreed to discontinue the proxy fight. The settlement terms did not require the company to make any of the operational and executive changes that Third Point was seeking. However, ten months later, Sotheby’s announced the hiring of a new CEO, the appointment of a new board chairman, and a plan to return capital to its investors.

While such settlements used to be rare, they now occur with significant frequency, and they have been attracting a great deal of media and practitioner attention. Understanding settlement agreements is important for obtaining a complete picture of the corporate governance landscape and the role of activism within it. Using a comprehensive, hand-collected dataset of settlement agreements, we provide in this study the first systematic empirical investigation of activist settlements. We study the drivers of settlements, their growth over time, their impact on board composition, their consequences for the operational and personnel choices that targets make, and the stock market reaction accompanying them. We further study the aftermath of settlements in terms of CEO turnover, payouts to shareholders, M&A activity, and operating performance.

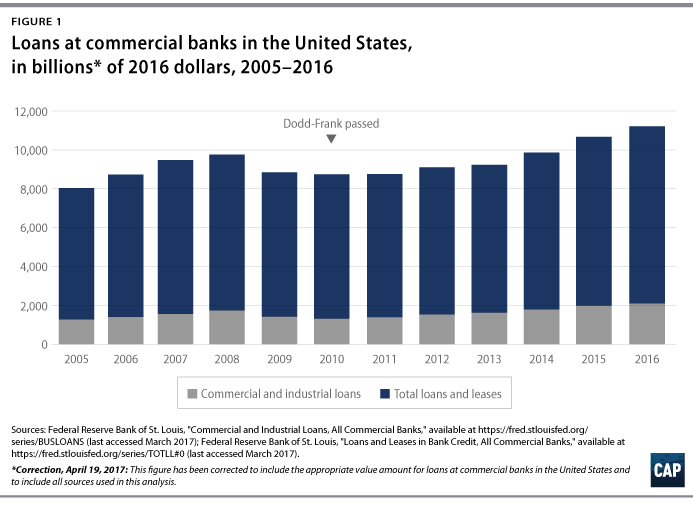

With the growing recognition of the importance of hedge fund activism, a large empirical literature on the subject has emerged (see Brav et al. (2015b) for a recent survey). This literature has studied the initiation of activist interventions—the time at which activists announce their presence, usually by filing Schedule 13(d) with the SEC after passing the 5% ownership threshold, and the stock market reactions accompanying such announcements. This literature has also studied extensively the changes in the value, performance and behavior of firms that take place during the years following activist interventions; among other things, researchers have studied the changes in Tobin’s Q, return on assets (ROA), payouts to shareholders, capital structure, likelihood of an acquisition, and accounting practices that ultimately follow activist interventions. But there has been limited empirical work on the “black box” in between—the channels through which activists’ influence is transmitted and gets reflected in targets’ economic outcomes. In particular, the determinants, nature and role of settlement agreements—and the cooperation between activists and targets that they introduce—have not been subject to a systematic empirical examination. We attempt to help fill this gap.

We begin by investigating the factors that determine the likelihood that an activist will be able to obtain a settlement agreement. Building on insights from the economics of settlements, we hypothesize that an activist will need to have a credible threat to win seats in a proxy fight to be able to extract a settlement agreement. Consistent with this hypothesis, we find that the likelihood of a settlement agreement in general, and a “high-impact” settlement agreement involving a substantial change in company leadership, covaries with several factors that are associated with improved odds for the activist in winning board seats in a proxy fight.

We quantify the upward trend in activist settlements. In particular, we show that the unconditional likelihood of a settlement increased threefold from the time period 2000-2002 (3%) to the period 2003-2005 (9%), increased by another 56% during 2006-2008 (14%) and by 29% during 2009-2011 (18%). These results hold when controlling for target and activist characteristics. Consistent with the view that settlements require activists having a credible threat to win board seats in a proxy fight, we argue that the increase in the settlement rate was driven by the growing willingness of institutional investors and proxy advisors to support activists, which in turns strengthened the credibility of the activist’s threat to win seats in a contest.

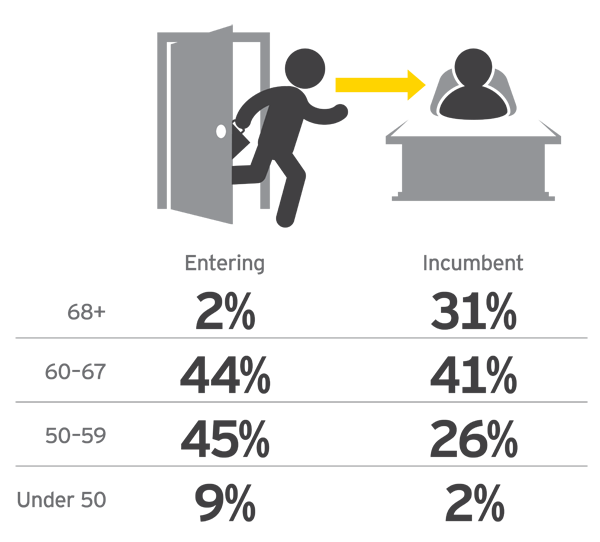

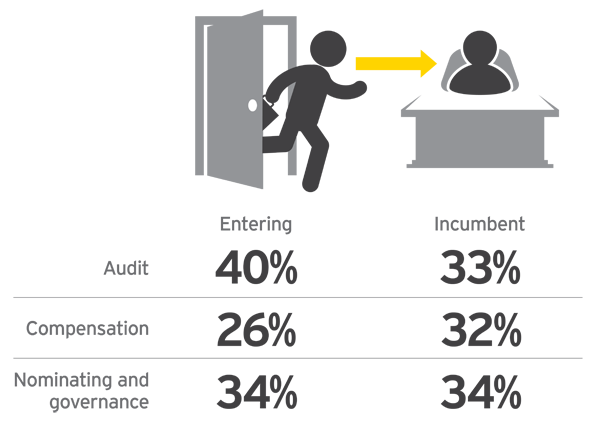

Turning to the terms of settlements, we explain the cost and difficulty of entering into contractual agreements that specify ultimate outcomes—the types of changes in operations, strategy, payouts or executive personnel that activists often seek. We document that settlements indeed rarely stipulate directly such outcomes. Rather, activists commonly settle on changes in board composition. We demonstrate that settlements are a key channel through which activists bring about board changes and we investigate the nature of these changes, showing that they bring about an increase in the number of activist-affiliated and activist-desired directors, well-connected directors and decrease the number of old and long-tenured directors.

Why do activists settle on changes in board composition if their ultimate goal is in bringing about operational or personnel changes? We argue that introducing individuals into the boardroom who are sympathetic, or at least open to the changes sought by the activist, is an intermediary step that can facilitate and bring about such changes. Consistent with this view, we show that, while settlements generally do not specify an ouster of the CEO, settlements are followed by a considerable increase in CEO turnover and in the performance-sensitivity of CEO turnover in the years following the settlement. Thus, settlements often plant the seeds for a subsequent CEO removal that is more face-saving to the CEO and the incumbent directors than an immediate ouster would be. Similarly, while settlement agreements generally do not specify operational changes, we document that such changes do follow in subsequent years. Settlements are followed by increased payouts to shareholders, a higher likelihood of target firms being acquired, and improvements in ROA.

We also investigate concerns raised by practitioners and the media that settlements between activists and targets enable activists to extract rents at the expense of other shareholders who are not “at the table” when the settlement is negotiated. We examine two suggested channels for such rent extraction and find little evidence that settlements provide activists with significant rents at other shareholders’ expense. First, we find no evidence that settlements enable activists to put directors on the board who are not supported by other shareholders. Directors who enter the board through settlements do not receive less voting support at the following annual general meeting than incumbent directors or those activist directors who get on the board without a settlement. Second, we find little evidence that settlements produce a significant incidence of “greenmail” by getting the target to purchase shares from the activist at a premium to the market price; buybacks of activist shares occur in a very small fraction of settlement agreements and, when they do occur, they are typically executed at the market price.

Finally, we analyze the stock market reactions accompanying the announcement of a settlement agreement. Settlements are accompanied by positive abnormal stock returns. Furthermore, we find that the positive abnormal returns are especially large when the settlement is “high impact” in terms of introducing two or more new directors or providing for an immediate CEO turnover. This pattern is consistent with the view that the market welcomes the boardroom and leadership changes that activist settlements produce and inconsistent with the view that such changes can be expected to be disruptive and detrimental to other shareholders.

Our study is available for download here.

*Lucian Bebchuk is Professor of Law, Economics, and Finance, and Director of the Program on Corporate Governance, at Harvard Law School; Alon Brav is Professor of Finance at Duke University; Wei Jiang is Professor of Finance at Columbia Business School; and Thomas Keusch is Assistant Professor at the Erasmus University School of Economics. This post is based on their study, Dancing with Activists, available here. This study is part of the research undertaken by the Project on Hedge Fund Activism of the Program on Corporate Governance. Related Program research includes The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Bebchuk, Brav and Jiang (discussed on the Forum here); and The Law and Economics of Blockholder Disclosure by Lucian Bebchuk and Robert J. Jackson Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

**Yvan Allaire, Voir la publication « L’IGOPP dévoile une étude sur l’enjeu des investisseurs activistes et leurs conséquences pour les conseils », site de l’IGOPP.