Quelle est la rémunération globale des administrateurs canadiens ?

C’est une question que beaucoup de personnes me posent, et qui n’est pas évidente à répondre !

L’article ci-dessous, publié par Martin Mittelstaedt, chercheur et ex-rédacteur au Globe and Mail, apporte un éclairage très intéressant sur la question de la rémunération des administrateurs canadiens.

Les études sur le sujet sont rares et donnent des résultats différents compte tenu de la taille, de la nature privée ou publique des entreprises, du secteur d’activité, des différentes composantes de la rémunération globale, etc.

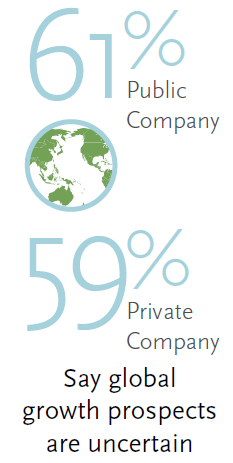

De manière générale, il semble que les rémunérations des administrateurs canadiens et américains soient similaires et que les postes d’administrateurs des entreprises publiques commandent une rémunération globale d’environ quatre fois la rémunération offerte par les entreprises privées.

Une étude montre que la base médiane de la rémunération des administrateurs de sociétés privées au Canada est de 25 000 $, avec un jeton de présence de 1 500 $ et quatre réunions annuelles. Le nombre d’administrateurs est de six, incluant trois administrateurs indépendants et une femme ! La somme de la rémunération globale s’établirait à environ 31 000 $ US. Mais on parle ici de grandes entreprises privées…

Le montant de la rémunération dépend aussi beaucoup des plans de distribution d’actions, des privilèges, des bonis, etc.

Évidemment, pour toute entreprise publique, il est facile de connaître la rémunération détaillée des administrateurs et des cinq hauts dirigeants puisque ces renseignements se retrouvent dans les circulaires aux actionnaires.

Je vous encourage à lire cet article. Vous en saurez plus long sur les raisons qui font que les informations sont difficiles à obtenir dans le secteur privé.

Bonne lecture !

How much is a director worth ?

Determining director compensation at private companies is more of an art than a science, with a wide range of practices and no one-size-fits-all formula.

Unlike publicly traded companies, where detailed information about director remuneration is as close as the nearest proxy circular, compensation at private boards is like “a black box,” according to Steve Chan, principal at Hugessen Consulting, who says retainers, meeting fees and share-based awards “are all over the map.”

Not much is known about private director compensation “for good reason,” observes David Anderson, president of Anderson Governance Group. “There is not a lot of data out there.”

PRIVATELY UNDERPAID?

Private company directorships can be prized assignments because they don’t involve the heavy compliance and regulatory burdens that occupy increasing amounts of time at public company boards.

But what private boards should be paid is difficult to determine, when there is little research to guide individual directors or companies. Some of the available data suggest private directors are being underpaid, at least relative to their public counterparts. But this information does not include the fact that the work may be different and much of the compensation at public boards may not ultimately pay off because it is linked to share price performance.

It is difficult to benchmark best practices with so little hard data, making it unsurprising that how best to set private company directors’ compensation is the most frequently asked question made by members to the ICD.

One of the few ongoing attempts to analyze compensation indicates remuneration is far higher at public boards, about four times higher in fact, although the amounts are skewed by the heavy use of stock-linked awards at publicly traded companies.

The private company survey, by Lodestone Global, was based on a questionnaire posed to members of the Young Presidents’ Organization, an international group of corporate présidents and CEOs, including many from Canada.

The Lodestone survey looked at medium-sized family or closely held firms, companies that are more established than early-stage startups, but smaller than large global corporations.

“The survey is not casually designed. The data is pretty rigorous and it’s global,” says Bernard Tenenbaum, managing partner at Princeton, N.J.-based Lodestone.

Tenenbaum says he started investigating private company board compensation because of the paucity of data on the subject. No one seemed to know what was going on. “People kept asking me, ‘Well how much should we pay directors?’ I’d say: ‘I don’t know. How much do you pay them now?’ And I started surveying.”

The firm’s most recent survey, based on 2014 data, had responses from more than 250 private companies, including 19 from Canada. The median revenue at the Canadian companies was $100-million, with the median number of employees at 325.

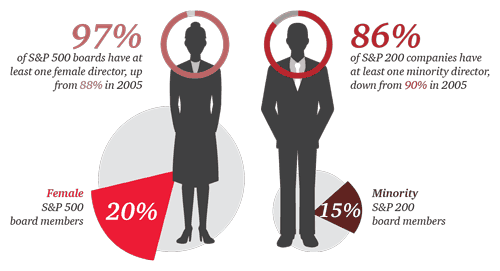

According to Tenenbaum, the median Canadian retainer was $25,000, with a $1,500 meeting fee and four meetings annually. The median number of directors was six, with three independent and one woman. The total of fees and retainers came to $31,000 (all dollar figures U.S.)

Interestingly, the overall U.S. compensation figure matched the Canadian one, but with a different composition. The median U.S. retainer was lower at $21,000, but the meeting fee was higher at $2,500. Including a few other miscellaneous items, like teleconference fees, U.S. compensation was $33,000, compared to $32,250 in Canada, a closeness that Tenenbaum termed “a kissing distance.”

The Lodestone figures give an indication of director compensation, although it is worth cautioning that the sample size is small, the figures are based on the median or middle-ranked firm, and there was a wide variety in size among the companies, given that they included a few smaller tech and industrial firms.

To benchmark private company director compensation, it is worthwhile to look at what comparable publicly traded companies are paying. One useful comparator is the smaller companies embedded in the BDO 600 survey of director compensation at medium-sized public companies. It has access to highly accurate data based on shareholder proxy circulars.

BDO’s 2014 survey found that among firms with revenue between $25-million and $325-million, cash compensation through retainer and committee fees averaged $54,000, while directors typically received another $65,000 in stock awards and options for a total of $119,000.

There is a small amount of information available in Canada on private board compensation, but the amount of data isn’t large enough to make generalized statements on remuneration and involves larger companies.

For example, in its director compensation, Canadian Tire Corp. breaks out amounts paid to the company’s non-publicly traded banking subsidiary, Canadian Tire Bank. In 2014, three directors on both boards were paid about $55,000 each for retainers and meeting fees for serving at the bank. Similarly, Loblaw Companies Ltd. paid $58,000 to a director who also served on President’s Choice Bank, a privately-held subsidiary.

The amounts are relatively low for blue-chip Canadian companies, but both banks are far smaller than their parent companies, with Canadian Tire Bank at $5.6-billion in assets and PC Bank at $3.3-billion.

Hugessen’s Chan says that in his experience, the larger, family-run private companies that have global operations compensate directors at roughly the same amounts as similarly sized public firms.

“Among the larger public companies versus the private companies, they’re comparable,” Chan says.

PUBLICLY EXPOSED

Tenenbaum says that based on his research and the figures from BDO, directors are being paid about $20,000 annually for taking on the added hassle of serving on a public company. He discounted the value of the stock-based compensation because it is conditional on share-price performance.

“There is a premium that you pay a director for taking the risk” of public company exposure, Tenenbaum says.

Directors also need to take into account some of the non-monetary factors of the board experience. Given that so much time on a public board is spent on compliance with regulatory requirements, being freed of this responsibility has value.

“When you’re on a private board, you don’t need to worry about all of the compliance that you have to worry about on a public company board,” says Larry Macdonald, who has served on both types of boards in the oil and gas sector. “You can spend more time on the issues which are probably more important to the company on a private board than you can on public board.”

Macdonald currently chairs publicly-traded Vermilion Energy Inc., but has also served on several private and volunteer boards.

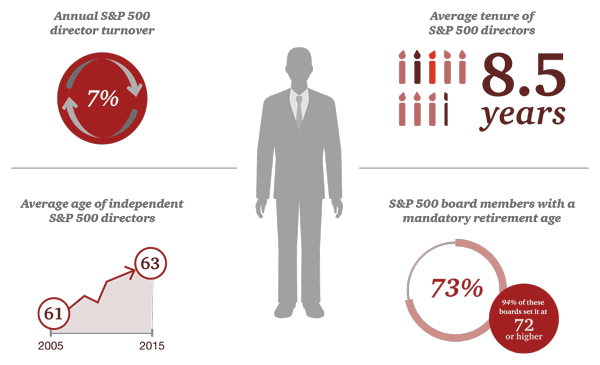

One consequence of the difference in focus is that private boards can often have fewer members because directors can be more focused on company business needs, rather than on compliance requirements. Decision making can also be quicker and easier.

Macdonald says a public board may need eight to 10 people to handle the volume of work, compared to only five or six on a similar private company. As an example of the efficiency of a private board, a company that has a particularly good year and wants to pay employees a bonus can easily decide to do so.

At a public company, however, making this payment wouldn’t be as straightforward. Directors would have to compile a detailed explanation of why they wanted to pay the bonus and include it in shareholder circulars.

While some companies are downgrading the importance of meeting fees, Macdonald thinks they are necessary, with a range of $1,000 to $1,500 being sufficient. “There should be a permeeting fee. You want your directors to show up in person, if at all possible, and if you’re not going to give them a permeeting fee they’re going to be phoning it in or not showing up, so you’ve got to keep everybody interested,” he says.

EQUITY COMPENSATION

He would set the retainer with an eye to any equity compensation. “If there is a pretty good option plan, I would think that $10,000 a year would be adequate, but if the option plan is weaker, you have to up the annual fee,” Macdonald says.

The amount of equity reserved for directors in private companies is a disputed topic. Tenenbaum says equity compensation at private companies, in his experience, is rare. But Chan says a figure often used is to allocate 10 percent of the equity for directors and executives.

If the director is “pounding the pavement with the CEO, a big chunk ofthe [equity] pool might go to directors,” Chan says.

The amount of equity reserved for executives and the board could be as high as 20 percent to 30 percent in the early life of a technology company, but lower than 10 percent in a capital intensive business. “It all depends on size. You’re not going to give 10 percent away of a $1-billion company,” he says.

Macdonald considers the 10 percent of stock reserved for management and directors a good ball park figure. The bulk of the stock typically goes to management, with one or two percent earmarked for directors, he says.

RICHER REWARDS

Public boards are typically egalitarian, with all directors receiving the same base compensation. Private boards, however, can and do pay differing amounts, depending on the specialized skills companies are trying to assemble among their directors. Macdonald says a private oil company looking to pick up older fields, which may have environmental issues, might award extra compensation to attract a director with recognized skills in health, safety and environment.

To be sure, compensation is only one factor in attracting directors to a board. Tenenbaum says academic research has found that the reasons directors cite to join boards are led by the quality of top management, the opportunity to learn and to be challenged. Personal prestige, compensation and stock ownership are far down the list.

These factors may explain why many people want to serve on private boards. “The qualitative experience of private company directors is quite different from public company directors,” says Anderson.

“They avoid a lot of the perceived risk of public company boards and they get the benefit of doing what, as business people, they really like doing, which is thinking about the business and applying their knowledge and experience to business problems.”

This article originally appeared in the Director Journal, a publication of the Institute of Corporate Directors (ICD). Permission has been granted by the ICD to use this article for non-commercial purposes including research, educational materials and online resources. Other uses, such as selling or licensing copies, are prohibited.