À l’occasion de la nouvelle année 2019, je partage avec vous une étude de la firme Russell Reynolds Associates sur les tendances en gouvernance selon différentes régions du monde.

L’article a été publié sur le site de Harvard Law School Forum par Jack « Rusty » O’Kelley, III, Anthony Goodman et Melissa Martin.

Ce qu’il y a de particulier dans cette publication ,c’est que l’on identifie cinq (5) grandes tendances globales et que l’on tente de prédire les Trends dans plusieurs régions du monde telles que :

(1) Les États-Unis et le Canada

(2) L’Union européenne

(3) La Grande-Bretagne

(4) Le Brésil

(5) l’Inde

(6) Le Japon

Les grandes tendances observées sont :

(1) la qualité et la composition du CA

(2) le degré d’attention apportée à la surveillance de la culture organisationnelle

(3) les activités des investisseurs qui limitent la primauté des actionnaires en mettant l’accent sur le long terme

(4) la responsabilité sociale des entreprises qui constitue toujours une variable critique et

(5) les investisseurs activistes qui continuent d’exercer une pression sur les CA.

Je vous recommande la lecture intégrale de cette publication pour vous former une opinion réaliste de l’évolution des saines pratiques de gouvernance. Les États-Unis et le Canada semblent mener la marche, mais les autres régions du globe ont également des préoccupations qui rejoignent les tendances globales.

C’est une lecture très instructive pour toute personne intéressée par la gouvernance des sociétés.

Bonne lecture et Bonne Année 2019 !

2019 Global & Regional Trends in Corporate Governance

Institutional investors (both active managers and index fund giants) spent the last few years raising their expectations of public company boards—a trend we expect to see continue in 2019. The demand for board quality, effectiveness, and accountability to shareholders will continue to accelerate across all global markets. Toward the end of each year, Russell Reynolds Associates interviews a global mix of institutional and activist investors, pension fund managers, proxy advisors, and other corporate governance professionals regarding the trends and challenges that public company boards may face in the coming year. This year we interviewed over 40 experts to develop our insights and identify trends.

Overview of Global Trends

In 2019, we expect to see the emergence or continued development of the following key global governance trends:

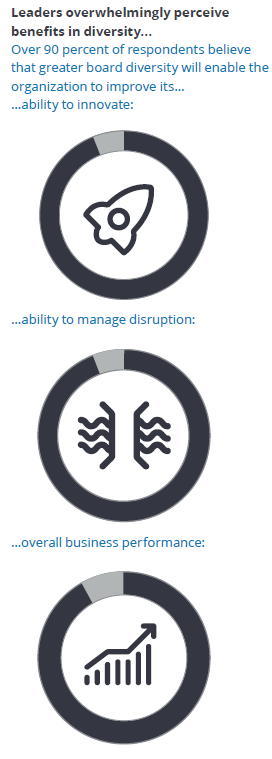

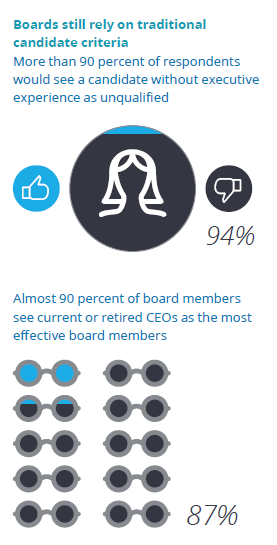

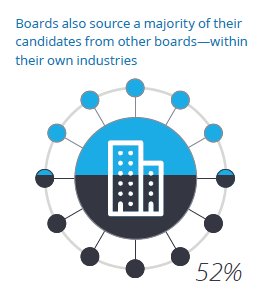

1. Board quality and composition are at the heart of corporate governance.

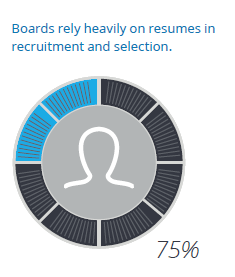

Since investors cannot see behind the boardroom veil, they have little choice but to rely on various governance criteria as a stand-in for board quality: whether the board is truly independent, whether its composition is deliberate and under regular review, and whether board competencies align with and support the company’s forward-looking strategy. Directors face increased scrutiny around how equipped the board is with industry knowledge, capital allocation skills, and transformation experience. Institutional investors are pushing to further encourage robust, independent, and regular board evaluation processes that may result in board evolution. Boards will need to be vigilant as they consider individual tenure, director overboarding, and gender imbalance—all of which may provoke votes against the nominating committee or its chair. Gender diversity continues to be an area of focus across many countries and investors. Companies can expect increased pressure to disclose their prioritization of board competencies, board succession plans, and how they are building a diverse pipeline of director candidates. Norges Bank Investment Management, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, has set a new standard for at least two independent directors with relevant industry experience on each of their 9,000 investee boards.

2. Deeper focus on oversight of corporate culture.

Human capital and intangible assets, including organizational culture and reputation, are important aspects of enterprise value, as they directly impact the ability to attract and retain top talent. Culture risk exists when there is misalignment between the values a company seeks to embody and the behaviors it demonstrates. Investors are keen to learn how boards are engaging with management on this issue and how they go about understanding corporate culture. A few compensation committees are including culture and broader human capital issues as part of their remit.

3. Investors placing limits on shareholder primacy and emphasizing long-termism.

The role of corporations in many countries is evolving to include meeting the needs of a broader set of stakeholders. Global investors are increasingly discussing social value; long-termism; and environment, social, and governance (ESG) changes that are shifting corporations from a pure shareholder primacy model. While BlackRock CEO Larry Fink’s 2018 letter to investee companies on the importance of social purpose and a strategy for achieving long-term growth generated discussion in the US, much of the rest of the world viewed this as further confirmation of the focus on broader stakeholder, as well as shareholder, concerns. Institutional investors are more actively focusing on long-termism and partnering with groups to increase the emphasis on long-term, sustainable results.

4. ESG continues to be a critical issue globally and is at the forefront of governance concerns in some countries.

Asset managers and asset owners are integrating ESG into investment decisions, some under the framework of sustainability or integrated reporting. The priority for investors will be linking sustainability to long-term value creation and balancing ESG risks with opportunities. ESG oversight, improved disclosure, relative company performance against peers, and understanding how these issues are built into corporate strategy will become key focus areas. Climate change and sustainability are critical issues to many investors and are at the forefront of governance in many countries. Some investors regard technology disruption and cybersecurity as ESG issues, while others continue to categorize them as a major business risk. Either way, investors want to understand how boards are providing adequate oversight of technology disruption and cyber risk.

5. Activist investors continue to impact boards.

Activist investors are using various strategies to achieve their objectives. The question for boards is no longer if, but when and why an activist gets involved. The characterization of activists as hostile antagonists is waning, as some activists are becoming more constructive with management. Institutional investors are increasingly open to activists’ perspectives and are deploying activist tactics to bring about desired change. Activists continue to pay close attention to individual director performance and oversight failures. We are seeing even more boards becoming “their own activist” or commissioning independent assessments to preemptively identify vulnerabilities. Firms such as Russell Reynolds are conducting more director-vulnerability analysis, looking at the strengths and weaknesses of board composition and proactively identifying where activists may attack director composition. In the following sections, we explore these trends and how they will impact the United States and Canada, the European Union and the United Kingdom, Brazil, India, and Japan.

The United States and Canada

Investor stewardship.

Eighty-eight percent of the S&P 500 companies have either Vanguard, BlackRock, or State Street as the largest shareholder, and together these investors collectively own 18.7 percent of all the shares in the S&P 500. Because the index funds’ creators are obligated to hold shares for as long as a company is included in a relevant index (e.g., Dow Jones, S&P 500, Russell 3000), the institutional investors view themselves as permanent capital. These investors view governance not as a compliance exercise, but as a key component of value creation and risk mitigation. Passive investors are engaging even more frequently with companies to ensure that their board and management are taking the necessary actions and asking the right questions. Investors want to understand the long-term value creation story and see disclosure showing the right balance between the long term and short term. They take this very seriously and continue to invest in stewardship and governance oversight. Several of the largest institutional investors want greater focus on long-term, sustainable results and are partnering with organizations to drive the dialogue toward the long term.

Board quality.

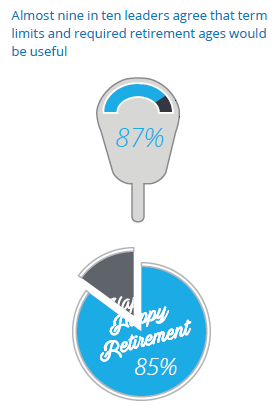

Investors are pushing for improved board quality and view board composition, diversity, and the refreshment process as key elements. There is similarly a push for richer insight into director skill relevancy. The Boardroom Accountability Project 2.0 has encouraged more companies to disclose a “board matrix,” setting out the skills, experiences, and demographic profile of directors. That practice is fast becoming the norm for proxy disclosure. Many more institutional investors want richer disclosure around director competencies and a clearer, more direct link between each director’s skills and the company’s strategy. As one investor noted, “We want to know why this collection of directors was selected to lead the company and whether they are prepared for change and disruption.” Some of the largest US institutional investors are pushing for better board succession and board evaluation processes and the use of external firms to assess board quality, composition, and effectiveness. Institutional investors are even more concerned about board succession processes and the continued use of automatic refreshment mechanisms (retirement ages and tenure limits) rather than a “foundational assessment process over time with a mix of internal and external reviewers.”

Board diversity.

In 2019, directors should expect more investors to vote against the nominating committee or its chair if there are no women on the board (or fewer than two women in some cases). Investors want to see an increased diversity of thought and experiences to better enable the board to identify risks and improve company performance. In the US, gender diversity has become a proxy for cognitive diversity. Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) has updated its policies on gender diversity for Russell 3000 and S&P 1500 companies and may recommend votes against nominating committee chairs or members beginning in 2020. This follows recent California legislation requiring gender diversity for California-headquartered companies. Some very large investors are starting to take a broader approach to diversity, particularly as it relates to ethnicity and race. In Canada, nearly 40 percent of TSX-listed companies have no women on their boards. Proxy advisors have recently established voting guidelines related to the disclosure of formal gender diversity policies and gender diversity by TSX-listed companies.

ESG.

Investors are pushing companies to consider their broader societal impact—both what they do and how they disclose it. ESG has moved from being a discrete topic to a fundamental part of how investors evaluate companies. They will increasingly focus on how companies explain their approach to value creation, the impact of the company on society, and how companies weigh various stakeholder interests. Other investors will continue to look at ESG primarily through a financial lens, screening for risk identification and measurement, incorporation of ESG into strategy and long-term value creation, and executive compensation. There is continued and growing focus in the US on sustainability and climate change across a range of sectors. In Canada, proactive companies will consider developing and disclosing their own ESG policies and upgrading boards—through both changes in director education and, on occasion, board composition—to ensure that directors are equipped to understand ESG risk.

Oversight of corporate culture.

Given many high-profile failures in corporate culture and leadership over the last few years, investors and regulators will expect more disclosure and will ask more questions regarding how a board understands the company’s culture. When engaging with institutional investors, boards should expect questions regarding how they are understanding and assessing the health of a corporation’s culture. Boards need to reflect on whether they really understand the company culture and how they plan to assess hot spots and potential issues.

Activist investing.

Shareholder activism remains part of the US corporate governance landscape and is continuing to grow in Canada. In Canada, the industries with the highest levels of activism include basic materials, energy, banking, and financial institutions, and emerging sectors with high growth potential (e.g., blockchain, cannabis) could be next. Proxy battles are showing no signs of slowing down, but activists are using other methods to promote change, such as constructive engagement. Canadian companies are also seeing an increase in proxy contests launched by former insiders or company founders. Experts in Canada anticipate this trend will continue and, as a result, increased shareholder engagement will be critical.

Executive compensation.

Investors are looking for better-quality disclosure around pay-for-performance metrics, particularly sustainability metrics linked to risk management and strategy. In the US, institutional investors may vote against pay plans where there is misalignment and against compensation committees where there is “excessive” executive pay for two or more consecutive years. Some investors are uncomfortable with stock performance being a primary driver of CEO compensation since it may not reflect real leadership impact. In Canada, investors are urging companies to adopt say-on-pay policies in the absence of a mandatory vote, even though such adoption rates have been sluggish to date. Investors will likely continue to push for this reform.

Governance codes.

Earlier this year, the Corporate Governance Principles of the Investor Stewardship Group (ISG) went into effect with the purpose of setting consistent governance standards for the US market. Version 2.0 of the Commonsense Principles of Corporate Governance was also published. US companies will want to consider proactive disclosure of how they comply with these sets of principles.

European Union

Investors more active.

Institutional investors are expanding resources for their engagement and stewardship teams in Europe. In 2019, investors will focus on connecting governance to long-term value creation through board oversight of talent management, ESG, and corporate culture. Additionally, some US activists are setting their sights on Europe and raising funds focused on European companies. Institutional investors are more willing to support activist investors if inadequate oversight by the board has led to poor share price and total shareholder return (TSR) performance.

Company and board diversity.

Though EU boards tend to have more women directors due to legislation and regulation, progress on gender diversity has not carried over into the C-suite. Boards can expect to engage with investors on this topic and will need to explain the root causes and plans to address it through talent management processes and diversity and inclusion initiatives. With gender diversity regulations already widely adopted across Europe, Austria has now also stipulated that public company boards have at least 30 percent women directors. However, since board terms are usually for five years, the full impact likely will not be visible until future election cycles.

ESG.

Many investors are encouraging use of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework for consistent measurement, assessment, and disclosure of ESG risks. Investors are likely to integrate climate-change competency and risk oversight into their voting guidelines in some form, and boards will need to demonstrate that they are thinking strategically about the opportunities, risks, and impact of climate change. A new legislative proposal in France could mandate that companies consider various stakeholders, the social environment, and the nonfinancial outcome of their actions.

Revised governance codes.

A recent study found strong compliance rates for the German Corporate Governance Code, except for the areas of executive remuneration and board composition recommendations. German boards should expect more investor engagement and pressure on these matters, including enhanced disclosure. Next year, the German code may include amendments impacting director independence and executive compensation. The revised governance code in the Netherlands focuses more closely on how long-term value creation and culture are vital elements within the governance framework. Denmark’s code now recommends that remuneration policies be approved at least every four years and bars retiring CEOs from stepping into the chairman or vice chairman role.

Board leadership.

Norges Bank Investment Management (commonly referred to as The Government Pension Fund Global) is pushing globally for the separation of CEO and chairman roles and independent chair appointments. In France, investors are focused on board composition and quality. Boards should expect to see continued pressure on separating the CEO and chairman roles as well as strengthening the role and prevalence of the lead director. Companies without a lead director could see negative votes against the reelection of the CEO/chair.

United Kingdom

Revised code.

Recent legislation and market activity have set the stage for the United Kingdom to implement governance reforms that will continue to influence global markets. The new UK Corporate Governance code will apply to reporting periods starting from January 1, 2019, although many companies have begun to apply it more quickly. The new code was complemented by updated and enhanced Guidance on Board Effectiveness to reemphasize that boards need to focus on improving their effectiveness—not just their compliance. Meanwhile the voluntary principle of “comply or explain” is itself being tested as the Kingman Review reconsiders the Financial Reporting Council’s powers and its twin role as both the government-designated regulator and the custodian of a voluntary code. Proxy advisors, who are growing more powerful, are also frequently voting against firms choosing to “explain” rather than comply. 2019 code changes include guidance around the board’s duty to consider the perspective of key stakeholders and to incorporate their interests into discussion and decisionmaking. Employees can be engaged via designating an existing non-executive director (already on the board), a workforce advisory committee, or a workforce representative on the board.

Board leadership and composition.

Other changes in the code include prioritizing non-executive chair succession planning and capping non-executive chair total tenure at nine years (including any time spent previously as a non-executive director)—a recommendation which could impact over 10 percent of the FTSE 350. Several investors noted that they understand the new tenure rule may cause unintended consequences around board chair succession planning. Investors are likely to focus on skills mix, diversity, and functional and industry experience. While directors can expect negative votes against their reelection if they are currently on more than four boards, better disclosure of director capacity and commitment may help sway investors.

Culture oversight.

The board’s evolving role in overseeing corporate culture—now explicit in the revised code—will be a primary focus for investors in 2019. The Financial Reporting Council has suggested that culture can be measured using several factors, such as turnover and absenteeism rates, reward and promotion decisions, health and safety data, and exit interviews. The code emphasizes that the board is responsible for a healthy culture that should promote delivering long-term sustainable performance. Auditor reform. Given public concern about recent corporate collapses, the role of external auditor and the structure of the audit firm market are under scrutiny. The government is under pressure to improve auditing and increase competition. Audit independence, rigor, and quality are likely to be examined, and boards may face greater pressure to change auditors more regularly. ISS is changing its policies for its UK/Ireland (and Continental European) policies beginning in 2019. ISS will begin tracking significant audit quality issues at the lead engagement partner level and will identify (when possible) any lead audit partners who have been linked to significant audit controversies.

Activist investors.

While institutional investors’ concerns center around the impact of disruption and how companies are responding with an eye toward long-termism and sustainability, activist campaigns continue to act as a potential counterweight. UK companies account for about 55 percent of activist campaigns in Europe, and UK companies will likely continue to be targeted next year.

Company diversity.

Diversity will continue to be a priority for board attention, including gender and ethnic diversity. The revised code broadened the role of the nominating committee to oversee the development of diversity in senior management ranks and to review diversity and inclusion initiatives and outcomes throughout the business.

Brazil

Outlook.

Following the highly polarized presidential election, Brazil is still facing some political uncertainty around the potential business and political agenda the new government will pursue. Despite recent ministry appointments being generally well received, global investors will likely still be cautious about investing in the country given the government’s deep history of entanglement with corporate affairs.

Governance reforms and stewardship.

Governance regulation is still in its early stages in Brazil and continues to be focused on overhauling compliance practices and implementing governance reforms. Securities regulator CVM recently issued guidelines regarding indemnity agreements between companies and board members (and other company stakeholders), which could lead to possible disclosure implications. The guidance serves to warn companies about potential conflicts of interest, and directors are cautioned to pay close attention to these new policies. Brazilian public companies are now required to file a comply-or-explain governance report as part of the original mandate stemming from the 2016 Corporate Governance Code, with an emphasis on the quality of such disclosures. Stewardship continues to be of growing importance, and boards are at the center of that discussion. The Association of Capital Market Investors is focusing on ensuring that the CVM and other market participants are holding companies to the highest governance standards not issuing waivers or failing to hold companies accountable for their actions.

Improved independence.

There is an ongoing push for more independence within the governance framework. More independent directors are being appointed to boards due to wider capital distribution. Brazil is working toward implementing reforms targeting political appointments within state-owned enterprises (SOE), but progress could slow depending upon the new government’s priorities. Recently, the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies approved legislation that would allow politicians to once again be nominated to SOE boards. The Federal Senate will soon decide on the proposal, but its approval could trigger a backlash. Organizations like the Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance are firmly positioning themselves against the law change, viewing it as a step back from recent governance progress. However, the Novo Mercado rules and Corporate Governance Code are strengthening the definition of independence and using shareholder meetings to confirm the independence of those directors.

Remote voting.

The recent introduction of the remote voting card for shareholders could have a major impact on boards. Public companies required to implement the new system should expect to see more flexibility and inclusion of minority shareholder-backed nominees on the ballot. While Brazil is making year-over-year progress toward minority shareholder protections, they continue to be a challenge.

Board effectiveness.

Experts anticipate increased pressure to upgrade board mechanics and processes, including establishing a nominations policy regarding board director and committee appointments, routine board evaluation processes, succession planning, and onboarding/training programs. CVM, along with B3 (the Brazilian stock exchange), continues to push for higher governance standards and processes. There is an increased focus on board and director assessment (whether internally or externally led) to ensure board effectiveness and the right board composition. Under the Corporate Governance Code, companies will have to comply or explain why they do not have a board assessment process.

Compensation disclosure.

For almost a decade, Brazilian companies used a court injunction (known as the “IBEF Injunction”) to avoid having to disclose the remuneration of their highest-paid executives. Now that this has been overturned, public companies will be expected to start disclosing compensation information for their highest-paid executives and board members. Companies are concerned that the disclosure may trigger a backlash among minority shareholders and negative votes against remuneration.

India

Regulatory reform.

Motivated by a desire to attract global investments, curb corruption, and strengthen corporate governance, India is continuing to push for regulatory reform. In the spring of 2018, much to the surprise of many, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) adopted many of the 81 provisions put forward by the Kotak Committee. The adoption of the recommendations has caused many companies to consider and aspire to meet this new standard. Kotak implementation has triggered a significant wave of governance implications centered around improving transparency and financial reporting. The adoption of these governance reforms is staggered, with most companies striving to reach compliance between April 2019 and April 2020.

Board composition, leadership, and independence.

Boards will face enhanced disclosure rules regarding the skills and experience of directors, which has triggered many companies to engage in board composition assessments. Directors will also be limited in the number of boards they can serve on simultaneously: eight in 2019; seven in 2020. The top 1,000 listed companies in India will need to ensure they have a minimum of six directors on their boards by April 2019, with the next 1,000 having an additional year to comply. Among other changes are new criteria for independence determinations and changes to director compensation. Additionally, the CEO or managing director role and the chair role must be separated and cannot be held by the same person for the top 500 listed companies by market capitalization. This will significantly change board leadership and control in many companies where the role was held by the same person, and it will boost overall independence. To further drive board and director independence, the definition of independence was strengthened, and board interlocks will receive greater scrutiny.

Board diversity.

India continues to make improvements toward gender diversity five years after the Companies Act of 2013 and ongoing pressure from investors and policymakers. Nevertheless, institutional investors and proxy advisors are calling for more progress, as a quarter of women appointments are held by family members of the business owners (and are thus not independent). Starting in 2019, boards of the top 500 listed companies will need to ensure they have at least one independent woman director; by 2020, the top 1,000 listed companies will need to comply.

Board effectiveness.

The reforms also include a requirement for the implementation of an oversight process for succession planning and updating the board evaluation and director review process.

Investor expectations.

Governance stakeholders are eager to see how much progress Indian companies will make during the next 18 months, but many are not overly optimistic given the magnitude of change required in such a short period of time. Investors are setting their expectations accordingly and understand that regional governance norms will not transform overnight. While it is unclear exactly how the government and regulators will respond to noncompliance, companies and their boards are feeling anxious about the potential repercussions and penalties.

Japan

Continued focus on governance.

The Japanese government continues to be a driving force for corporate governance improvements. To make Japan more attractive to global investors, policymakers are increasingly focused on improving board accountability. Despite a trend toward more proactive investor stewardship, regulatory bodies including the Financial Services Agency continue to lead reforms, with several new comply-or-explain guidelines added to the Amended Corporate Governance Code that came into effect in 2018. These guidelines, such as minimum independence requirements, establishing an objective CEO succession and dismissal process, and the unloading of cross-shareholdings, are aimed at enhancing transparency.

Director independence.

Director independence has been a concern for investors, with outside directors taking only about 31 percent of board seats. Though some observers perceive a weakening of language in the code regarding independence, investors are unlikely to lower their expectations and standards. The amended code now calls for at least one-third of the board to be composed of outside directors (up from the quota requirement of two directors that existed previously). The change is intended to encourage transparency and accountability around the board’s decision-making process. Starting next year, ISS will adopt a similar approach to its Japanese governance policies, employing a one-third independence threshold as well.

Executive compensation.

Given recent scandals, institutional investors and regulators will continue to pay close attention to the structure of executive compensation. Performance-based compensation plans will be a major area of focus in 2019. More companies are introducing new types of equity-based compensation schemes, such as restricted stock, and are expected to follow the trend into next year. Board diversity. Over 50 percent of listed companies still have no women on their boards. To upgrade board quality and performance, investors will likely engage more forcefully on gender diversity, board composition and processes, board oversight duties and roles, and the board director evaluation process.

ESG.

In 2019, boards can expect more shareholder interest in sustainability metrics and strategy. Investors are keen to see enhanced disclosure that aids their understanding of value creation and the link to performance targets, as well as explanations concerning board monitoring.

Activist investing.

Activism continues to rise in Japan, and we expect that trend to continue. Activists are showing a willingness to demand a board seat and engage in proxy battles, and institutional investors are increasingly willing to support the activist recommendations.

Governance practices.

Investors also will be paying close attention to several other governance practices, such as the earlier disclosure of proxy materials and delivery in digital format, and protecting the interest of minority shareholders. The code further emphasizes succession planning by requiring companies to implement a fair and transparent process for the CEO’s removal and succession. As a result, more companies are introducing nominating committees and discussing

CEO succession.

Companies are also being urged to unload their cross-shareholdings (when a listed company owns stock of another company in the same listing) and adopt controls that will determine whether the ownership of such equity is appropriate. Such holdings are likely to be policed more by regulators due to the tendency of such holdings to insulate boards from external pressure, including takeover bids.

___________________________________________________________

*Jack “Rusty” O’Kelley, III is Global Leader of the Board Advisory & Effectiveness Practice, Anthony Goodman is a member of the Board Consulting and Effectiveness Practice, and Melissa Martin is a Board and CEO Advisory Group Specialist at Russell Reynolds Associates.at Russell Reynolds Associates. This post is based on a Russell Reynolds memorandum by Mr. O’Kelley, Mr. Goodman, and Ms. Martin.