Annual board evaluations are now commonplace for both for-profit and non-profit organizations, with specific board evaluation recommendations forming a key component in nearly every major corporate governance standard, review or report internationally.

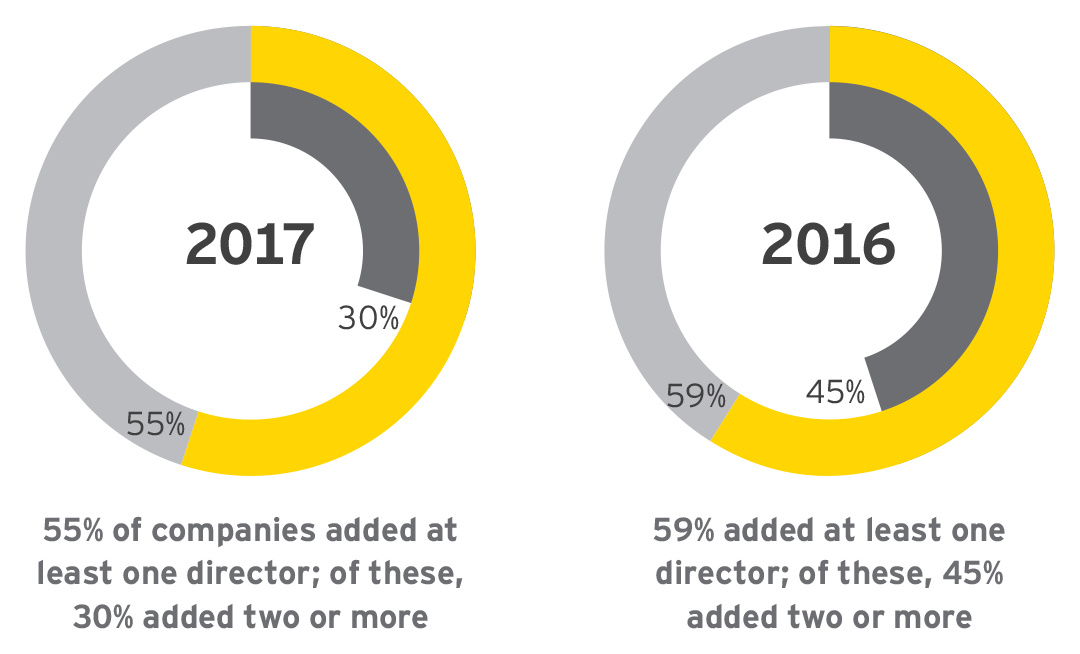

Recent data on US boards from the global consulting firm Spencer Stuart shows that 98% of S&P 500 boards conduct a board evaluation of some type, although only about a third review the board as a whole, individual directors and committees as part of the process. In the UK, the majority of boards on the FTSE 150 conduct board reviews, with 60.7% conducting their evaluations internally, while 38% of boards used an external facilitator. Encouragingly, PwC reports that in 2017 68% of public company directors in the US say that the board has taken action based on the results of their last board review, which was an increase on the 49% from PwC’s survey in 2016.

In a cross sector review of board effectiveness by the UK arm of Grant Thornton, more than 60% off those surveyed agreed or strongly agreed that there were “adequate processes in place to evaluate the performance of the whole board.” But are “adequate processes” good enough? For example, adequate processes might mean a perfunctory activity is conducted annually to meet listing requirements or pay lip service to best practice governance. And what about the 40% of boards in the UK survey that do not have adequate processes?

Our experience, having been involved in many board evaluations in large and small, for-profit and non-profit organisations, is that the effectiveness of board reviews ranges from counterproductive exercises, which exacerbate already fractious and poorly performing boards, to truly transformational change leading to superior governance and organisational outcomes. Further, our experience suggests that understanding the relative advantages and disadvantages of the different types of board reviews, and properly planning and implementing the board’s evaluation significantly increases the likelihood of positive outcomes.

A seven step framework for board evaluations

We wrote our recently released book, Reviewing Your Board—A Guide to Board and Director Evaluation, to address this need for more information about board and director evaluations to give boards and their directors the opportunity to think about board evaluations and how they can be carried out to add—rather than subtract—value to the organization.

Our approach to effective board and director evaluations uses a seven-step framework (see Figure 1) that asks the vital questions all boards should consider when planning an evaluation. While these questions must be asked for all board evaluations, the combined answers can be quite different. Thus, although the seven questions may be common to each, the subsequent review processes can range markedly in their scope, complexity and cost. Further, while our framework is described sequentially, in practice, most boards will not follow such a linear process.

Figure 1

Framework for a board evaluation

Source: Kiel, et al., 2018, p. 4

1. What are our objectives?

The first (and, in our opinion, most important) aspect of any evaluation is establishing why the board is doing it. The primary motivation can be characterized as “conformance” or “value adding”:

– conformance focuses on meeting the expectations of external scrutiny through compliance with various laws and following appropriate governance standards—whether mandated or self-imposed; and

– value adding focuses on improving both organizational and board performance. For example, taking proactive steps to ensure the board is effective in bringing new talent into the boardroom to maintain a proper mix of skills.

In practice, most board reviews will be aimed at meeting both conformance and value-adding objectives.

Without a solid rationale shared by the directors, any evaluation is likely to meet resistance and/or fail. There are many aspects of its performance the board may wish to evaluate. Apart from a desire to contribute to firm performance, many boards feel that regular evaluation contributes significantly to group processes within the board. A regular board review can indicate potential problems or differences of opinion that can be addressed before they become a source of conflict.

Generally, the answer to the first question in the seven-step framework will fall into one of the following two categories:

– organizational leadership, e.g., “We want to clearly demonstrate our commitment to performance management”; or

– problem resolution, e.g., “We do not seem to have the appropriate skills, competencies or motivation on the board”.

Clearly identified objectives enable the board to set specific goals for the evaluation and make decisions about the scope of the review; e.g., the approach the board will take, how many people will be involved, how much time and money will be allocated.

2. Who will be evaluated?

Comprehensive governance evaluations can entail reviewing the performance of a wide range of individuals and groups. Boards need to consider three groups:

– the board as whole (including committees);

– individual directors (including the role of the chair); and

– key governance personnel (generally the CEO and corporate/company secretary).

Considerations such as cost or time constraints, however, may prevent reviewing all three groups.

Alternatively, a board may have a very specific objective for the review process that does not require the review of all individuals and groups identified. In both cases, an effective evaluation requires the board to select the most appropriate individuals or groups to review, based on its objectives.

3. What will be evaluated?

The third stage in establishing a framework for a board evaluation involves deciding the criteria for the evaluation process. This is necessary whether the board is seeking general or specific performance improvements, and will suit boards seeking to improve areas as diverse as board processes, director skills, competencies and motivation, or even boardroom relationships.

To cover the range of objectives the board may have, including meeting any compliance requirements, board evaluations generally use some form of leading practice framework, such as the National Association of Corporate Directors’ Key Agreed Principles or the Business Roundtable Principles of Corporate Governance. Of course, a comprehensive list of areas for investigation will need to be balanced with the scope of the evaluation and the resources available for the process. At this stage, a realistic assessment of the resources available, a component of which is the time availability of directors and other key governance personnel, can be made.

4. Who will be asked?

The vast majority of board and director evaluations concentrate exclusively on the board as the sole sources of information for the evaluation process. However, this discounts other potentially rich sources of feedback. Participants in the evaluation can be drawn from within or from outside the organization. Internally, directors, the CEO, senior executives and, in some cases, other management personnel and employees may be able to provide useful feedback on elements of the governance system. Externally, depending on the ownership structure, shareholders may provide valuable data for the review. Similarly, in some situations, key stakeholders such as government departments or agencies, major clients and suppliers may have close links with the board and be in a position to provide useful information on its performance.

5. What techniques will be used?

Depending on the degree of formality, the objectives of the evaluation, and the resources available, boards may choose between a range of qualitative and quantitative techniques. Quantitative data are in the form of numbers. They can be used to answer questions of “how much” or “how many”. Questionnaire-based surveys are by far the most common form of quantitative technique used in board evaluations and can be an important information-gathering tool.

Questions of “what”, “how”, and “why” require qualitative research methods. The three main methods used for collecting qualitative data are:

- Interviews, either one-on-one or in small groups, provide an excellent way of assessing directors’ perceptions, meaning and constructions of reality by asking for information in a way that allows them to express themselves in their own terms;

- Board meeting observation is especially useful when the evaluation objectives relate to issues of boardroom dynamics or relationships between individuals; and

- Document analysis of board packs, governance policies and similar can also be a rich source of information to identify areas of improvement in board processes.

When the board evaluation’s objectives are to identify governance issues, qualitative research is particularly useful. Qualitative data does, however, have several drawbacks. The major one being that interpreting the results requires judgment and experience on the part of the person undertaking the review and analysis.

There is no best methodology. Research techniques need to be adapted to the evaluation objectives and board context. However, there are advantages to be gained from combining a questionnaire with interviews. The questionnaire (most often delivered online) allows directors to benchmark the board along a series of dimensions (e.g. very poor to very good; 1 to 5; etc.), which allows directors to see where they have differing viewpoints from other directors. This can then be followed-up by interviews to allow directors to provide further context to the topics covered in the questionnaire and to raise areas of concern not covered in the survey.

6. Who will do the evaluation?

Who conducts the evaluation process will depend on whether the review is to be conducted internally or externally and what methodology is chosen. Internal reviews are conducted within the organization, either by one or more directors or governance personnel such as the corporate secretary. External reviews are conducted by external parties, most often either specialist consulting firms in corporate governance, large generalist consulting firms or law firms.

Internal reviews are more likely to provide board members with confidence surrounding the confidentiality of the process and are likely to cost less. All of these are important considerations when making the decision.

There are, however, several limitations to an internally conducted review. The internal reviewer may lack the skills required (e.g., interview technique, survey design), they are likely to have a bias (often unconscious) that carries over into the assessment and it is a less transparent process where the review process is carried out by one of the board’s own. Perhaps most significantly, the review is likely to achieve little if the reviewer (e.g., the chair) is the source of the problems or it may not be appropriate given the objectives of the review.

An external facilitator can offer a number of advantages including that:

– a good external facilitator is more likely to have undertaken a significant number of reviews and will often provide important insights into techniques, comparison points and new ideas;

– an external party often aids transparency and objectivity;

– a good external party can play a mediating role for boards facing sensitive issues through being the messenger for difficult matters involving group dynamics and egos.

Ultimately, factors such as the complexity of the governance problems faced, the experience of the board and cost considerations will determine whether the board decides to conduct the evaluation internally or seek external advice. However, it is now becoming more and more common for boards to alternate between an internal review one year and an external review the next.

7. What will we do with the results?

The evaluation’s objectives should be the determining factor when deciding to whom the results will be released. Most often, the board’s central objective will be to agree a series of actions that it can take to improve governance. Since the effectiveness of the governance system relies on people within the organization, communicating the results to all directors and key governance personnel is critical for boards seeking performance improvement. Where the objective of the board evaluation is to assess the quality of board—management relationships, a summary of the evaluation may also be shared with the senior management team.

If the board wishes to build its reputation for transparency and/or to develop relationships with external stakeholders, a positive, focused board evaluation is an excellent way of demonstrating that it is serious about governance and is committed to improving its performance. Obviously, when considering what information to communicate externally, a balance needs to be struck between transparency on the one hand and the need for shareholders and other external stakeholders to retain faith in the board’s ability and effectiveness on the other hand. Such communication outline how the evaluation was conducted (e.g. internal or external review), the focus of the review (e.g. role fulfilment) and, perhaps, some of the major outcomes (e.g. identified need to further focus on strategy or requirements for new skills on the board).

In communicating board review outcomes, it should be remembered that the confidentiality of the process contributes significantly to full and frank insights being provided by participants and provides the board with defensible results. As such, director confidentiality must be protected.

Implementing the outcomes

Once the annual performance evaluation is over, the board’s attention will move on to other issues and any stimulus for change that may have come when the results were first delivered can dissolve. Worse still, directors along with any executives who participated in the process will feel the evaluation has been a waste of their valuable time if recommendations for improvement were accepted, but not acted on. Therefore, it is critical that any agreed actions that come out of an evaluation are implemented and monitored. Many boards include a review of action steps as an agenda item to be tracked at each meeting. Milestones can be established for the achievement of the action plans and progress reviewed until all agreed changes have been implemented.

Other approaches to board evaluation

There are a number of different approaches to evaluating board performance that may better suit a board’s objectives and differ from the “traditional” board, individual director (self and peer), chair or committee evaluations. For example, board skills assessment and board maturity assessment all serve a different purpose and can bring about significant improvements to the board’s performance if appropriately implemented.

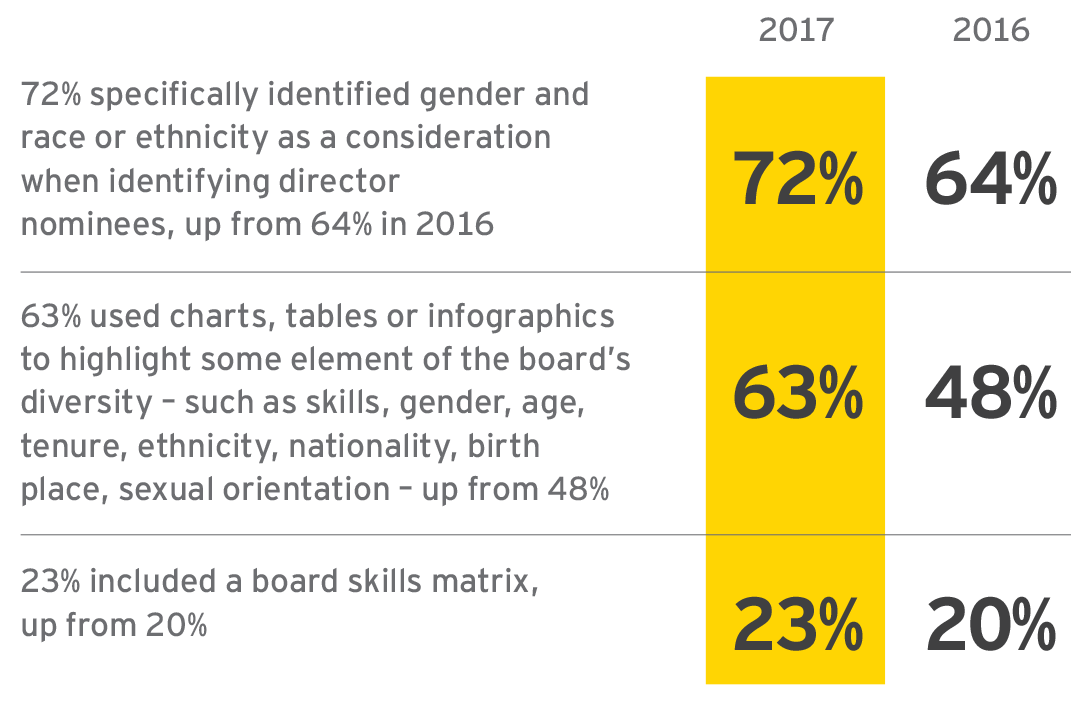

If the board’s primary objective in undertaking a review of its performance is to focus on the current and required skills of the board, a dedicated skills analysis rather than a board evaluation would be the best way to identify the skills that currently exist on the board and consequently, highlight any skills gaps.

More recently, a new type of board review is being used, board maturity assessment. Maturity assessments involve benchmarking the board against what is regarded as good practice. Maturity models have become popular in several management disciplines. They involve establishing different levels of practice from “basic” to “advanced” over the key functions of an activity, based on contemporary views of best practice. In corporate governance, the key functions include the role of the board in relation to the CEO, risk practices, compliance, the conduct of board meetings, effective use of board committees, and so on. The governance activity of the organization in all these governance dimensions is then assessed by an external evaluator experienced in corporate governance against the maturity model to provide a current maturity rating. Directors’ views can be part of the process, with directors indicating what level of maturity is desirable for the organization given its circumstances. Looking at the gaps between the current level of governance practice and the appropriate level as agreed by directors shows where better practice may be implemented. This approach also has the benefit of indirectly educating directors as to what is good governance practice.

Conclusion

Performance evaluation is an increasingly important feature of boardrooms across the globe. These reviews have benefits for individual directors, boards and the organizations for which they work. Boards also need to recognize that the evaluation process is an effective team-building, ethics-shaping activity. Our observation is that boards often neglect the process of engagement when undertaking evaluations; unfortunately, boards that fail to engage their members are missing a major opportunity for developing a shared set of board norms and inculcating a positive board and organizational culture. In short, the process is as important as the content.

______________________________________________________________-

Endnotes

1Spencer Stuart, 2017 Spencer Stuart US Board Index, www.spencerstuart.com/research-and-insight/ssbi-2017, accessed 7 March 2018.(go back)

2Spencer Stuart, 2017 Spencer Stuart UK Board Index, www.spencerstuart.com/research-and-insight/uk-board-index-2017, accessed 7 March 2018.(go back)

3 PwC, 2017 Annual Corporate Directors Survey, https://www.pwc.com/us/en/governance-insights-center/annual-corporate-directors-survey/assets/pwc-2017-annual-corporate–directors–survey.pdf, accessed 7 March 2018.(go back)

4Grant Thornton UK, 2017, The Board: creating and protecting value, https://www.grantthornton.co.uk/globalassets/1.-member-firms/united-kingdom/pdf/publication/board-effectiveness-report-2017.pdf, accessed 8 March 2018, p 10(go back)

5G Kiel, G Nicholson, J Tunny, and J Beck, 2018, Reviewing Your Board: A Guide to Board and Director Evaluation, Australian Institute of Company Directors, Sydney.(go back)

6National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD), 2011, Key Agreed Principles, https://www.nacdonline.org/files/PDF/KEY%20AGREED%20PRINCIPLES%202011.pdf, accessed 1 May 2018.(go back)

7Business Roundtable, 2016, Business Roundtable Principles of Corporate Governance, https://businessroundtable.org/sites/default/files/Principles-of-Corporate-Governance-2016.pdf, accessed 1 May 2018.(go back)