Thank you for your role in overseeing the Vanguard funds’ sizable investment in your company. We depend on you to represent our funds’ ownership interests on behalf of our more than 20 million investors worldwide. Our investors depend on Vanguard to be a responsible steward of their assets, and we promote principles of corporate governance that we believe will enhance the long-term value of their investments.

At Vanguard, a long-term perspective informs every aspect of our investment approach, from the way we manage our funds to the advice we give our investors. Our index funds are structurally long-term, holding their investments almost indefinitely. And our active equity managers—who invest nearly $500 billion on our clients’ behalf—are behaviorally long-term, with most holding their positions longer than peer averages. The typical dollar invested with Vanguard stays for more than ten years.

A long-term perspective also underpins our Investment Stewardship program. We believe that well-governed companies are more likely to perform well over the long run. To this end, we consider four pillars when we evaluate corporate governance practices:

- The board: A high-functioning, well-composed, independent, diverse, and experienced board with effective ongoing evaluation practices.

- Governance structures: Provisions and structures that empower shareholders and protect their rights.

- Appropriate compensation: Pay that incentivizes relative outperformance over the long term.

- Risk oversight: Effective, integrated, and ongoing oversight of relevant industry- and company-specific risks.

These pillars guide our proxy voting and engagement activity, and we hope that by sharing this framework with you, you’ll have a better perspective on our approach to stewardship.

I’d like to highlight a few key themes that are increasingly important in our stewardship efforts:

Good governance starts with a great board.

We believe that when a company has a great board of directors, good results are more likely to follow.

We view the board as one of a company’s most critical strategic assets. When the board contributes the right mix of skill, expertise, thought, tenure, and personal characteristics, sustainable economic value becomes much easier to achieve. A thoughtfully composed, diverse board more objectively oversees how management navigates challenges and opportunities critical to shareholders’ interests. And a company’s strategic needs for the future inform effectively planned evolution of the board.

Gender diversity is one element of board composition that we will continue to focus on over the coming years. We expect boards to focus on it as well, and their demonstration of meaningful progress over time will inform our engagement and voting going forward. There is compelling evidence that boards with a critical mass of women have outperformed those that are less diverse. Diverse boards also more effectively demonstrate governance best practices that we believe lead to long-term shareholder value. Our stance on this issue is therefore an economic imperative, not an ideological choice. This is among the reasons why we recently joined the 30% Club, a global organization that advocates for greater representation of women in boardrooms and leadership roles. The club’s mission to enhance opportunities for women from “schoolroom to boardroom” is one that we think bodes well for broadening the pipeline of great directors.

Directors are shareholders’ eyes and ears on risk.

Risk and opportunity shape every business. Shareholders rely on a strong board to oversee the strategy for realizing opportunities and mitigating risks. Thorough disclosure of relevant and material risks—a key board responsibility—enables share prices to fully reflect all significant known (and reasonably foreseeable) risks and opportunities. Given our extensive indexed investments, which rely on the price-setting mechanism of the market, that market efficiency is critical to Vanguard and our clients.

Climate risk is an example of a slowly developing and highly uncertain risk—the kind that tests the strength of a board’s oversight and risk governance. Our evolving position on climate risk (much like our stance on gender diversity) is based on the economic bottom line for Vanguard investors. As significant long-term owners of many companies in industries vulnerable to climate risk, Vanguard investors have substantial value at stake.

Although there is no one-size-fits-all approach, market solutions to climate risk and other evolving disclosure practices can be valuable when they reflect the shared priorities of issuers and investors. Our participation in the Investor Advisory Group to the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) reflects our belief that materiality-driven, sector-specific disclosures will better illuminate risks in a way that aids market efficiency and price discovery. We believe it is incumbent on all market participants—investors, boards, and management alike—to embrace the disclosure of sustainability risks that bear on a company’s long-term value creation prospects.

Engagement builds mutual understanding and a basis for progress.

Timely and substantive dialogue with companies is core to our investment stewardship approach. We see engagement as mutually beneficial: We convey Vanguard’s views and we hear companies’ perspectives, which adds context to our analysis.

Our funds’ votes on ballot measures—171,000 discrete items in the past year alone—are an outcome of this process, not the starting point. As we analyze ballot items, particularly controversial ones, we often invite direct and open-ended dialogue with the company. We seek management’s and the board’s perspectives on the issues at hand, and we evaluate them against our principles and leading practices. To understand the full picture, we often also engage with other investors, including activists and shareholder proponents. Our goal is that a fund’s ultimate voting decision does not come as a surprise. Our ability to make informed decisions depends on maintaining an ongoing exchange of ideas in a setting in which we can cover the intention and strategy behind the issues.

Yet our engagement activities are not solely focused on the ballot. Because our funds will hold most of their portfolio companies practically permanently, it’s important for us to build relationships with boards and management teams that transcend a transactional focus on any specific issue or vote. Engagement is a process, not an event, whose value only grows over time. A CEO we engaged with once said, “You can’t wait to build a relationship until you need it,” and that couldn’t be more true.

The opportunity to articulate our perspectives and understand a board’s thinking on a range of topics—anchored at the intersection of the firm’s strategy and its enabling governance practices—is a crucial part of our stewardship obligations. Although ballot items are reduced to a series of binary choices—yes or no, for or against—engagement beyond the ballot enables us to deal in nuance and in dialogue that drives meaningful progress over time.

There is a growing role for independent directors in engagement, both on issues over which they hold exclusive purview (such as CEO compensation and board composition/succession) and on deepening investors’ understanding of the alignment between a company’s strategy and governance practices. Our interest in engaging with directors is by no means intended to interfere with management’s ownership of the message on corporate strategy and performance. Rather, we believe it’s appropriate for directors to periodically hear directly from and be heard by the shareowners on whose behalf they serve.

* * *

Our focus on corporate governance and investment stewardship has been and will continue to be a deliberate manifestation of Vanguard’s core purpose: “To take a stand for all investors, to treat them fairly, and to give them the best chance for investment success.” Our four pillars and our increased focus on climate risk and gender diversity are not fleeting priorities for Vanguard. As essentially permanent owners of the companies you lead, we have a special obligation to be engaged stewards actively focused on the long term. Our Investment Stewardship team—available at InvestmentStewardship@vanguard.com—stands ready to engage with you and your leadership teams on matters of mutual importance to our respective stakeholders. Thank you for valuing our perspective and being our partner in stewardship.

Sincerely,

William McNabb III

Chairman and Chief Executive Officer

The Vanguard Group, Inc.

* * *

Investment Stewardship 2017 Annual Report

Our values and beliefs

“To take a stand for all investors, to treat them fairly, and to give them the best chance for investment success.”

—Vanguard’s core purpose

Vanguard’s core values of focus, integrity, and stewardship are reflected every day in the way that we engage with our clients, our crew (what we call our employees), and our community. We view our Investment Stewardship program as a natural extension of these values and of Vanguard’s core purpose. Our clients depend on us to be good stewards of their assets, and we depend on corporate boards to prudently oversee the companies in which our funds invest. That is why we believe we have a unique mission to advocate for a world in which the actions and values of public companies and of investors are aligned to create value for Vanguard fund shareholders over the long term.

We believe well-governed companies will perform better over the long term.

Effective corporate governance is more than the collection of a company’s formal provisions and bylaws. A board of directors serves on behalf of all shareholders and is critical in establishing trust and transparency and ensuring the health of a company—and of the capital markets—over time. This board-centric view is the foundation of Vanguard’s approach to investment stewardship. It guides our discussions with company directors and management, as well as our voting of proxies on the funds’ behalf at shareholder meetings around the globe. Great governance starts with a board of directors that is capable of selecting the right management team, holding that team accountable through appropriate incentives, and overseeing relevant risks that are material to the business. We believe that effective corporate governance is an important ingredient for the long-term success of companies and their investors. And when portfolio companies perform well, so do our clients’ investments.

We value long-term progress over short-term gain.

Because our funds typically own the stock of companies for long periods (and, in the case of index funds, are structurally permanent holders of companies), our emphasis on investment outcomes over the long term is unwavering. That’s why we deliberately focus on enduring themes and topics that drive long-term value, rather than solely short-term results. We believe that companies and boards should similarly be focused on long-term shareholder value—both through the sustainability of their strategy and operations, and by managing the risks most material to their long-term success.

Our approach

Vanguard’s Investment Stewardship team comprises an experienced group of senior leaders and analysts who are responsible for representing Vanguard shareholders’ interests through industry advocacy, company engagement, and proxy voting on behalf of the Vanguard funds. The team also houses an internal research and communications function that is active in developing Vanguard’s views, policies, and ongoing approach to investment stewardship. Our data and technology group supports every aspect of our Investment Stewardship program.

We take a thoughtful and deliberate approach to investment stewardship.

Our team supports effective corporate governance practices in three ways:

Advocating for policies that we believe will enhance the sustainable, long-term value of our clients’ investments. We promote good corporate governance and responsible investment through thoughtful participation in industry events and discussions where we can expand our advocacy and enhance our understanding of investment issues.

Engaging with portfolio company executives and directors to share our corporate governance principles and learn about portfolio companies’ corporate governance practices. We characterize our approach as “quiet diplomacy focused on results”—providing constructive input that will, in our view, better position companies to deliver sustainable value over the long term for all investors.

Voting proxies at company shareholder meetings across each of our portfolios and around the globe. Because of our ongoing advocacy and engagement efforts, companies should be aware of our governance principles and positions by the time we cast our funds’ votes.

Our process is iterative and ongoing

Our four pillars

Board

Good governance begins with a great board of directors. Our primary interest is to ensure that the individuals who represent the interests of all shareholders are independent (both in mindset and freedom from conflicts), capable (across the range of relevant skills for the company and industry), and appropriately experienced (so as to bring valuable perspective to their roles). We also believe that diversity of thought, background, and experience, as well as of personal characteristics (such as gender, race, and age), meaningfully contributes to the board’s ability to serve as effective, engaged stewards of shareholders’ interests. If a company has a well-composed, high-functioning board, good results are more likely to follow.

Structure

We believe in the importance of governance structures that empower shareholders and ensure accountability of the board and management. We believe that shareholders should be able to hold directors accountable as needed through certain governance and bylaw provisions. Among these preferred provisions are that directors must stand for election by shareholders annually and must secure a majority of the votes in order to join or remain on the board. In instances where the board appears resistant to shareholder input, we also support the right of shareholders to call special meetings and to place director nominees on the company’s ballot.

Compensation

We believe that performance-linked compensation policies and practices are fundamental drivers of the sustainable, long-term value for a company’s investors. The board plays a central role in determining appropriate executive pay that incentivizes performance relative to peers and competitors. Providing effective disclosure of these practices, their alignment with company performance, and their outcomes is crucial to giving shareholders confidence in the link between incentives and rewards and the creation of value over the long term.

Risk

Boards are responsible for effective oversight and governance of the risks most relevant and material to each company in the context of its industry and region. We believe that boards should take a thorough, integrated, and thoughtful approach to identifying, understanding, quantifying, overseeing, and—where appropriate—disclosing risks that have the potential to affect shareholder value over the long term. Importantly, boards should communicate their approach to risk oversight to shareholders through their normal course of business.

By the numbers: Voting and engagement

Engagement and voting trends

|

2015 proxy season |

2016 proxy season |

2017 proxy season |

| Company engagements |

685 |

817 |

954 |

| Companies voted |

10,560 |

11,564 |

12,974 |

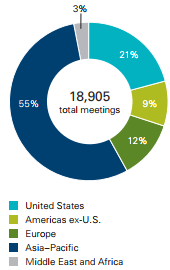

| Meetings voted |

12,785 |

16,740 |

18,905 |

| Proposals voted |

124,230 |

157,506 |

171,385 |

| Countries voted in* |

70 |

70 |

68 |

* The number of countries can vary each year. In certain markets, some companies do not hold shareholder meetings annually.

Note: The annual proxy season is from July 1 to June 30.

Our voting

Proxy voting reflects our governance pillars worldwide.

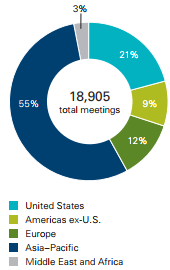

Meetings voted by region

Note: Data pertains to voting activity from July 1, 2016, through June 30, 2017

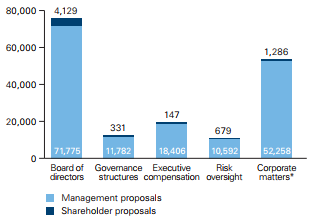

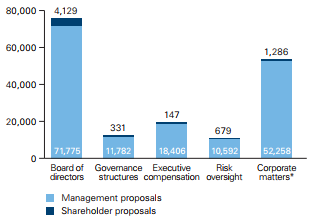

Global voting activity

* Includes more than 26,000 proposals related to capitalization; 8,000 proposals related to mergers and acquisitions; 16,000 routine business proposals; and 1,000 other shareholder proposals.

Note: Data pertains to voting activity from July 1, 2016, through June 30, 2017.

Our engagement

We engage with companies of all sizes.

| Market Capitalization |

% of 2017 proxy season engagements |

| Under $1 billion |

19% |

| $1 billion–under $10 billion |

44% |

| $10 billion–under $50 billion |

24% |

| $50 billion and over |

13% |

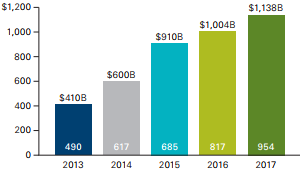

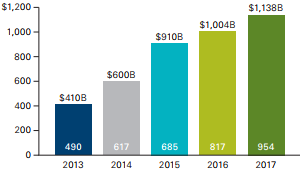

Our engagement with portfolio companies has grown significantly over time.

Number of engagements and assets represented

Note: Dollar figures represent the market value of Vanguard fund investments in companies with which we engaged as of June 30, 2017.

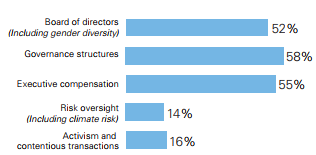

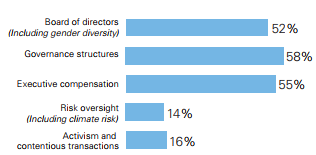

We engage on a range of topics aligned with our four pillars

Frequency of topics discussed during Vanguard engagements (%)

Note: Figures do not total 100%, as individual engagements often span multiple topics.

Boards in focus: Vanguard’s view on gender diversity

One of our most fundamental governance beliefs is that good governance begins with a great board of directors. We believe that diversity among directors—along dimensions such as gender, experience, race, background, age, and tenure—can strengthen a board’s range of perspectives and its capacity to make complex, fully considered decisions.

While we have long discussed board composition and diversity with portfolio companies, gender diversity has emerged as one dimension on which there is compelling support for positive effects on shareholder value. In recent years, a growing body of research has demonstrated that greater gender diversity on boards can lead to better company performance and governance.

Companies should be prepared to discuss—in both their public disclosures and their engagement with investors—their plans to incorporate appropriate diversity over time in their board composition. While we believe that board evolution is a process, not an event, the demonstration of meaningful progress over time will inform our engagement and voting going forward.

Boards in focus: Gender diversity

Engagement case studies

Gender diversity on boards was an important topic of engagement for us during the 12 months ended June 30, 2017. Below are summary examples of discussions we had on the subject.

High-impact engagement on gender diversity

Over several interactions with a U.S. industrial company, our team shared Vanguard’s perspective on board composition and evaluation. The company had undergone recent leadership transitions and was open to amending elements of its governance structure to align with best practices. We expressed particular support for meaningful gender diversity and expressed concern that the board previously had only one female director in its recent history.

Right after this year’s annual general meeting, the company announced it was adding four new directors with diverse experience, including two women. This outcome is the best-case scenario: The board welcomed shareholder input, we shared our view on best corporate governance practices, and the board ultimately incorporated our perspective into its board evolution process.

A denial of diversity’s value

A Canadian materials company that had consistently underperformed was governed by an entrenched, all-male board with seemingly nominal independence from the CEO. A 2017 shareholder resolution asked the company to adopt and publish a policy governing gender diversity on the board. Before voting, Vanguard engaged with the company to learn about its board evolution process, including its perspective on gender diversity. The engagement revealed that the company understood neither the value of gender diversity nor the importance of being responsive to shareholders’ concerns. Despite verbally endorsing gender diversity, the company resisted specifying a strategy or making a commitment to achieve it. The board, when seeking new members, relied solely on recommendations from current directors, a practice that can entrench the current board’s perspective and limit diversity. Our funds voted in support of the shareholder resolution, and we will continue to engage and hold the board accountable for meaningful progress over time.

Mixed results from an ongoing engagement

A U.S. consumer discretionary company had no women on its board, a problem magnified by its medium-term underperformance relative to peers, a classified board structure, and a lengthy average director tenure. We engaged with management twice between the 2016 and 2017 annual meetings to share our perspective on the importance of gender diversity and recommend that they make it a priority for future board evolution and director searches.

In its 2017 proxy, the company described board diversity as critical to the firm’s sustainable value and named gender as an element of diversity to be considered during the director search and nomination process. The company has since added a non-independent woman to the board. Although this move is directionally correct, it does not fully address our concerns; we will continue to encourage the company to add gender diversity to its ranks of independent directors.

Risk in focus: Vanguard’s view on climate risk

As the steward of long-term shareholder value for more than 20 million investors, Vanguard closely monitors how our portfolio companies identify, manage, and mitigate risks—including climate risk. Our approach to climate risk is evolving as the world’s and business community’s understanding of the topic matures.

This year, for the first time, our funds supported a number of climate-related shareholder resolutions opposed by company management. We are also discussing climate risk with company management and boards more than ever before. Our Investment Stewardship team is committed to engaging with a range of stakeholders to inform our perspective on these issues, and to share our thinking with the market, our portfolio companies, and our investors.

Risk in focus: Climate risk

A Q&A with Glenn Booraem, Vanguard’s Investment Stewardship Officer

Vanguard is an investment management company. Why should Vanguard fund investors be concerned about climate risk?

Mr. Booraem: Climate risk has the potential to be a significant long-term risk for companies in many industries. As stewards of our clients’ long-term investments, we must be finely attuned to this risk. We acknowledge that our clients’ views on climate risk span the ideological spectrum. But our position on climate risk is anchored in long-term economic value—not ideology. Regardless of one’s perspective on climate, there’s no doubt that changes in global regulation, energy consumption, and consumer preferences will have a significant economic impact on companies, particularly in the energy, industrial, and utilities sectors.

Why the shift in Vanguard’s assessment of climate risk, and why now?

Mr. Booraem: We’ve been discussing climate risk with portfolio companies for several years. It has been, and will remain, one of our engagement priorities for the foreseeable future. This past year, we engaged with more companies on this issue than ever before, and for the first time our funds supported two climate-related shareholder resolutions in cases where we believed that companies’ disclosure practices weren’t on par with emerging expectations in the market. As with other issues, our point of view has evolved as the topic has matured and, importantly, as its link to shareholder value has become more clear.

What is your top concern when you learn that a company in which a Vanguard portfolio invests does not have a rigorous strategy to evaluate and mitigate climate risk?

Mr. Booraem: Our concern is fundamentally that in the absence of clear disclosure and informed board oversight, the market lacks insight into the material risks of investing in that firm. It’s of paramount importance to us that the market is able to reflect risk and opportunity in stock prices, particularly for our index funds, which don’t get to select the stocks they own. When we’re not confident that companies have an appropriate level of board oversight or disclosure, we’re concerned that the market may not accurately reflect the value of the investment. Because we represent primarily long-term investors, this bias is particularly problematic when underweighting long-term risks inflates a company’s value.

Now that Vanguard has articulated a clear stance on climate risk, what can portfolio companies expect?

Mr. Booraem: First, companies should expect that we’re going to focus on their public disclosures, both about the risk itself and about their board’s and management’s oversight of that risk. Thorough disclosure is the foundation for the market’s understanding of the issue. Second, companies should expect that we’ll evaluate their disclosures in the context of both their leading peers and evolving market standards, such as those articulated by the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). Third, they should expect that we’ll listen to their perspective on these and other matters. And finally, they should see our funds’ proxy voting as an extension of our engagement. When we consider a shareholder resolution on climate risk, we give companies a fair hearing on the merits of the proposal and consider their past commitments and the strength of their governance structure.

Engagement case studies

In the 12 months ended June 30, 2017, the topic of climate risk disclosure grew in frequency and prominence in our engagements with companies, particularly those in the energy, industrial, and utilities sectors, where climate risk was addressed in nearly every conversation we had. Below are examples of our engagements on climate risk.

Two companies’ commitments to enhanced disclosure

Our team led similar engagements with two U.S. energy companies facing shareholder resolutions on climate risk. One resolution requested that the first company publish an annual report on climate risk impacts and strategy. At the second company, a resolution requested disclosure of the company’s strategy and targets for transitioning to a low- carbon economy. In both cases, when we engaged with the companies, their management teams committed to improving their climate risk disclosure. Given the companies’ demonstrated responsiveness to shareholder feedback and commitment to improving, our funds did not support either shareholder proposal. Our team will continue to track and evaluate the companies’ progress toward their commitments as we consider our votes in future years.

A vote against a risk and governance outlier For years we engaged with a U.S. energy company that lagged its peers on climate risk disclosure and board accessibility. This year, a shareholder proposal requesting that the company produce a climate risk assessment report demonstrated a compelling link between the requested disclosures and long-term shareholder value. Because the board serves on behalf of shareholders and plays a critical role in risk oversight, we believed it was appropriate to seek a direct dialogue with independent directors about climate risk. Management resisted connecting the independent directors with shareholders, making the company a significant industry outlier in good governance practice. Without the confidence that the board understood or represented our view that climate risk poses a material risk in the energy sector, our team viewed the climate risk and governance issues as intertwined. Ultimately, our funds voted for the shareholder proposal and withheld votes on relevant independent directors for failing to engage with shareholders.

A vote for greater climate risk disclosure

A shareholder proposal at a U.S. energy company asked for an annual report with climate risk disclosure, including scenario planning. Through extensive research and engagements with the company’s management, its independent directors, and other industry stakeholders, our team identified governance shortfalls and a clear connection to long-term shareholder value. The company lagged its peers in disclosure, risk planning, and board oversight and responsiveness to shareholder concerns. Crucially, although the company’s public filings identified climate risk as a material issue, it failed to articulate plans for mitigation or adaptation. A similar proposal last year garnered significant support, but the company made no meaningful changes in response. Engagement had limited effect, so our funds voted for the shareholder proposal.

* * *

This post was excerpted from a Vanguard report; the complete publication is available here.