Aujourd’hui, je cède la parole à Mme Nicolle Forget*, certainement l’une des administratrices de sociétés les plus chevronnées au Québec (sinon au Canada), qui nous présente sa vision de la gouvernance « réglementée » ainsi que celle du rôle des administrateurs dans ce processus.

L’allocution qui suit a été prononcée dans le cadre du Colloque sur la gouvernance organisée par la Chaire de recherche en gouvernance de sociétés le 6 juin 2014. Je pensais tout d’abord faire un résumé de son texte, mais, après une lecture attentive, j’en ai conclu que celui-ci exposait une problématique de fond et constituait une prise de position fondamentale en gouvernance. Il me semblait essentiel de vous faire partager son article au complet.

Nous avons souvent abordé les conséquences non anticipées de la réglementation, principalement celles découlant des exigences de divulgation en matière de rémunération. Cependant, dans son allocution, l’auteure apporte un éclairage nouveau, inédit et audacieux sur l’exercice de la gouvernance dans les sociétés publiques.

Elle présente une solide argumentation et expose clairement certains malaises vécus par les administrateurs eu égard à la lourdeur des mécanismes réglementaires de gouvernance. Les questionnements présentés en conclusion de l’article sont, en grande partie, fondés sur sa longue expérience comme membre de nombreux conseils d’administration.

Comment réagissez-vous aux constats que fait Mme Forget ? Les autorités réglementaires vont-elles trop loin dans la prescription des obligations de divulgation ? Pouvons-nous éviter les effets pervers de certaines dispositions sans pour autant nuire au processus de divulgation d’informations importantes pour les actionnaires et les parties prenantes.

Vos commentaires sont les bienvenus. Je vous souhaite une bonne lecture.

MALAISE AU CONSEIL | Les effets pervers de l’obligation de divulgation en matière de rémunération

par

Nicolle Forget*

Merci aux organisateurs de ce colloque de me donner l’occasion de partager avec vous quelques constatations et interrogations qui m’habitent depuis quatre ou cinq ans concernant diverses obligations imposées aux entreprises à capital ouvert (inscrites en Bourse). Je souligne d’entrée de jeu que la présentation qui suit n’engage que moi.

Depuis l’avènement de quelques grands scandales financiers, ici et ailleurs, on en a mis beaucoup sur le dos des administrateurs de sociétés. On voudrait qu’un administrateur soit un expert en semblable matière. Il ne l’est pas. Il arrive avec son bagage, c’est pourquoi on l’a choisi. On lui prépare un programme de formation pour lui permettre de comprendre l’entreprise au conseil de laquelle il a accepté de siéger, mais il n’en saura jamais autant que la somme des savoirs de l’entreprise. C’est utopique de s’attendre au contraire. Même un administrateur qui ne ferait que cela, siéger au conseil de cette entreprise, ne le pourrait pas.

Des questions reviennent constamment dans l’actualité : où étaient les administrateurs ? N’ont-ils rien vu venir ou rien vu tout court? Ont-ils rempli leur devoir fiduciaire? Tout juste si on ne conclut pas qu’ils sont tous des incompétents. Les administrateurs étaient là. Ils savaient ce que l’on a bien voulu leur faire savoir. (ex. Saccage de la Baie-James. Les administrateurs de la SEBJ, convoqués en Commission parlementaire à Québec, au printemps 1983, ont appris, par un avocat venu y témoigner, l’existence d’un avis juridique qu’il avait préparé à la demande de la direction. La SEBJ poursuivait alors les responsables du saccage et un très long procès était sur le point de commencer. Avoir eu connaissance de son contenu, au moment où il a été livré au PDG, aurait eu un impact sur nos décisions. J’étais alors membre du conseil d’administration).

Posons tout de suite que la meilleure gouvernance qui soit n’empêchera jamais des dirigeants qui veulent cacher au conseil certains actes d’y parvenir — surtout si ces actes sont frauduleux. Même avec de belles politiques et de beaux codes d’éthique, plusieurs directions d’entreprise trouvent encore qu’un conseil d’administration n’est rien d’autre qu’un mal nécessaire. Les administrateurs sont parfois perçus comme s’ingérant dans les affaires de la direction ou dans les décisions qu’elle prend. Aussi, ces dirigeants ont-ils tendance à placer les conseils devant des faits accomplis ou des dossiers tellement bien ficelés qu’il est difficile d’y trouver une fissure par laquelle entrevoir une faille dans l’argumentation au soutien de la décision à prendre. Pourtant, et nous le verrons plus loin, en vertu de la loi, le conseil « exerce tous les pouvoirs nécessaires pour gérer les activités et les affaires internes de la société ou en surveiller l’exécution ».

Les conseils d’administration, comme les entreprises et leurs dirigeants, sont soumis à quantité de législations, réglementations, annexes à celles-ci, avis, lignes directrices et autres exigences émanant d’autorités multiples — et davantage les entreprises œuvrent dans un secteur d’activités qui dépasse les frontières d’une province ou d’un pays. Et, selon ce que l’on entend, il faudrait que l’administrateur ait toujours tout vu, tout su…

Malaise !

En 2007, Yvan Allaire écrivait que « … la gouvernance par les conseils d’administration est devenue pointilleuse et moins complaisante, mais également plus tatillonne, coûteuse et litigieuse ; les dirigeants se plaignent de la bureaucratisation de leur entreprise, du temps consacré pour satisfaire aux nouvelles exigences » 1. Denis Desautels, lui, signalait que « Certains prétendent que le souci de la conformité aux lois et aux règlements l’emporte sur les discussions stratégiques et sur la création de valeur. Et d’autres, que l’adoption ou l’endossement des nouvelles normes n’est pas toujours sincère et, qu’au fond, la culture de l’entreprise n’a pas réellement changé » 2.

Pour mémoire, voyons quelques obligations (de base) d’un administrateur de sociétés.

Au Québec, la Loi sur les sociétés par actions (L.r.Q., c. S-31.1) prévoit que les affaires de la société sont administrées par un conseil d’administration qui « exerce tous les pouvoirs nécessaires pour gérer les activités et les affaires internes de la société ou en surveiller l’exécution » (art. 112) et que, « Sauf dans la mesure prévue par la loi, l’exercice de ces pouvoirs ne nécessite pas l’approbation des actionnaires et ceux-ci peuvent être délégués à un administrateur, à un dirigeant ou à un ou plusieurs comités du conseil. »

De façon générale, les administrateurs de sociétés sont soumis aux obligations auxquelles est assujetti tout administrateur d’une personne morale en vertu du Code civil. « En conséquence, les administrateurs sont notamment tenus envers la société, dans l’exercice de leurs fonctions, d’agir avec prudence et diligence de même qu’avec honnêteté et loyauté dans son intérêt » (art. 119). L’intérêt de la société, pas l’intérêt de l’actionnaire. La loi fédérale présente des concepts semblables. (La Cour Suprême du Canada a d’ailleurs rappelé dans l’affaire BCE qu’il n’existe pas au Canada de principe selon lequel les intérêts d’une partie — les actionnaires, par exemple — doivent avoir priorité sur ceux des autres parties.)

Si la société fait appel publiquement à l’épargne, elle devient un émetteur assujetti. Alors s’ajoutent les règles de la Bourse concernant les exigences d’inscription initiale ainsi que celles concernant le maintien de l’inscription. S’ajoutent aussi les obligations édictées dans la Loi sur les valeurs mobilières (L.R.Q., c. V-1.1), de même que les règlements qui en découlent, et dont l’Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) est chargée de l’application. L’émetteur assujetti est tenu aux obligations d’information continue. Si vous êtes un administrateur ou un haut dirigeant d’un tel émetteur ou même d’une filiale d’un tel émetteur, vous êtes un initié avec des obligations particulières.

L’article 73 de cette Loi stipule que tel émetteur « … fournit, conformément aux conditions et modalités déterminées par règlement, l’information périodique au sujet de son activité et de ses affaires internes, dont ses pratiques en matière de gouvernance, l’information occasionnelle au sujet d’un changement important et toute autre information prévue par règlement. ». « L’émetteur assujetti doit organiser ses affaires conformément aux règles établies par règlement en matière de gouvernance ». (art.73.1)

La mission de l’Autorité, (entendre ici AMF) telle qu’énoncée à l’article 276.1 de la Loi sur les valeurs mobilières se décline comme suit :

- Favoriser le bon fonctionnement du marché des valeurs mobilières ;

- Assurer la protection des épargnants contre les pratiques déloyales, abusives et frauduleuses ;

- Régir l’information des porteurs de valeurs mobilières et du public sur les personnes qui font publiquement appel à l’épargne et sur les valeurs émises par celles-ci ;

- Encadrer l’activité des professionnels des valeurs mobilières et des organismes chargés d’assurer le fonctionnement d’un marché des valeurs mobilières.

Dans sa loi constituante, l’Autorité a une mission plus élaborée qui reprend sensiblement les mêmes thèmes, mais en appuyant davantage sur la protection des consommateurs de produits et utilisateurs de services financiers. (art.4, L.R.Q., c. A-33.2)

Aux termes de la législation en vigueur, « L’Autorité exerce la discrétion qui lui est conférée en fonction de l’intérêt public » (art.316, L.R.Q., c. V-1.1) et un règlement pris en vertu de la présente loi confère un pouvoir discrétionnaire à l’Autorité » (art.334). En outre, toujours selon cette Loi, « Les instructions générales sont réputées constituer des règlements dans la mesure où elles portent sur un sujet pour lequel la loi nouvelle prévoit une habilitation réglementaire et qu’elles sont compatibles avec cette loi et les règlements pris pour son application. »

Je vous fais grâce du Règlement sur les valeurs mobilières (Décret 660-83 ; 115 G.O.2, 1511) ; quant à l’Annexe (51-102A5), portant sur la Circulaire de sollicitation de procuration par la direction, et celle (51-102A6) portant spécifiquement sur la Déclaration de la rémunération de la haute direction, j’y reviendrai plus loin.

Ceci pour une société qui ne fait affaire qu’au Québec, et à l’exclusion de toutes les autres législations et les nombreux règlements portant sur un secteur d’activité en particulier. Pensons juste aux activités qui peuvent affecter l’environnement, même de loin. Alors, si une société fait affaire ailleurs au Canada et aux É.-U. ou sur plusieurs continents — ajoutez des obligations, des modes différents de divulgation de l’information — et cela peut vous donner une petite idée de « l’industrie » qu’est devenue la gouvernance d’entreprise avec l’obligation de livrer l’information en continu et sous une forme de plus en plus détaillée. Et les administrateurs devraient tout savoir, avoir tout vu…

Les très nombreuses informations que nous publions rencontrent-elles l’objectif à l’origine de ces exigences ? Carol Liao soutient que « les autorités réglementaires sont par définition orientées vers l’actionnaire ce qui aurait mené à une augmentation des droits de ces derniers, bien au-delà de ce que les lois canadiennes (sur les sociétés) envisageaient. » On a vu plus haut que la Loi sur les sociétés par actions édicte que « les administrateurs sont notamment tenus envers la société dans l’exercice de leurs fonctions, d’agir avec prudence et diligence de même qu’avec honnêteté et loyauté dans son intérêt ». Se pourrait-il que « ce qui est dans l’intérêt supérieur des actionnaires ne coïncide pas avec une meilleure gouvernance ? (doesn’t align with better governance – that’s where the practice falls down »3.)

J’aime à croire que l’origine de l’obligation qui est faite aux entreprises de dire qui elles sont, ce qu’elles font, comment elles le font, et avec qui elles le font, est la protection du petit investisseur — vous et moi qui plaçons nos économies en prévision de nos vieux jours — comme disaient les anciens.

À moins d’y être obligé par son travail, qui comprend le contenu des circulaires de sollicitation de procuration par la direction, émises à l’intention des actionnaires ? Les Notices annuelles ? D’abord, qui les lit? Chaque fois que l’occasion m’en est donnée, je pose la question – et partout le même commentaire : si je n’avais pas les lire je ne les lirais pas. La quantité de papier rebute en partant ; la complexité des informations à publier en la forme prescrite est difficile à comprendre pour un non-expert, alors imaginez pour un petit investisseur. Si même il s’aventure à lire le document.

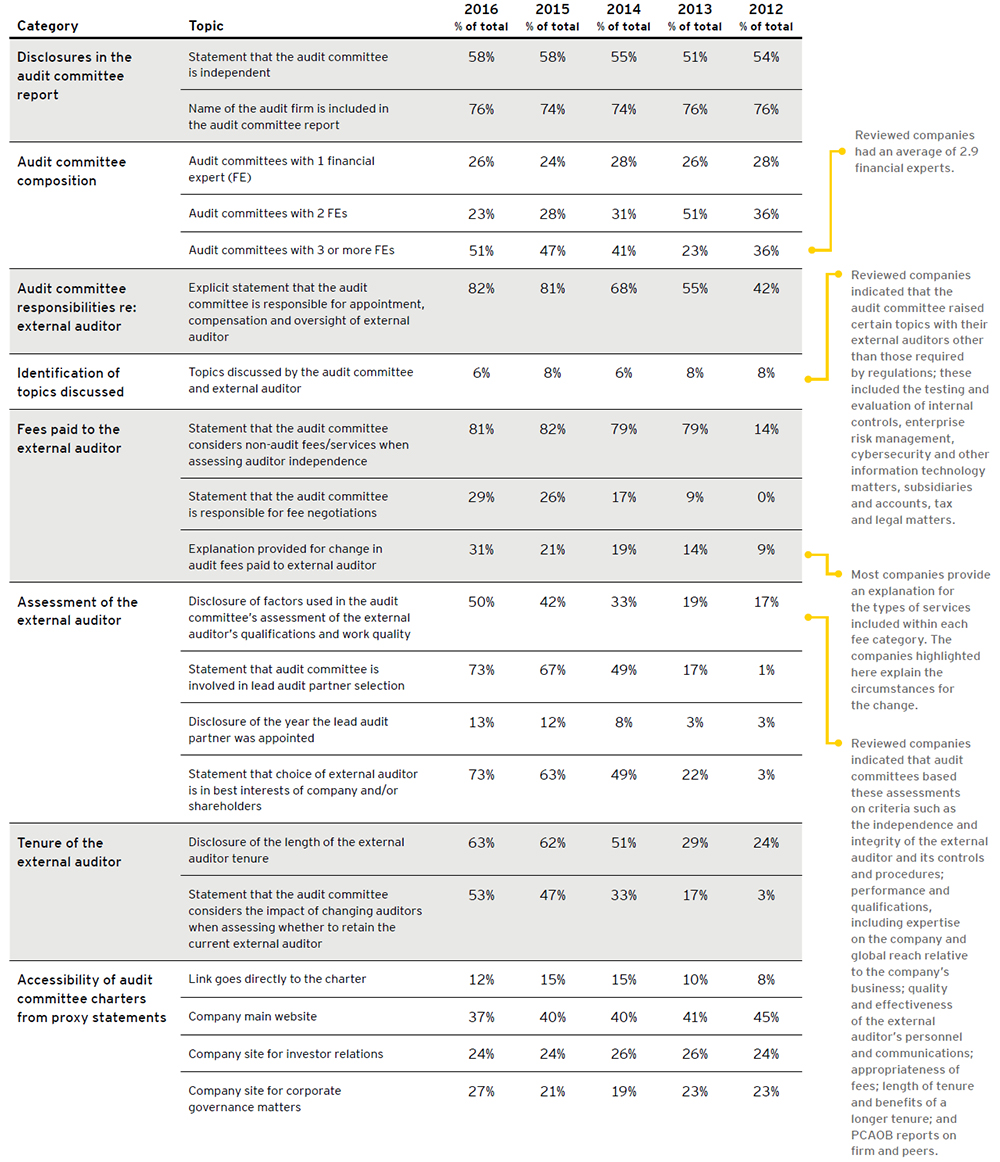

Donc, si tant est que les circulaires et les notices ne soient pratiquement lues que par ceux qui n’ont pas le choix de le faire, il serait peut-être temps de se demander à quoi, ou plutôt, à qui elles servent ? Et à quels coûts pour l’entreprise. A-t-on une idée de combien d’experts s’affairent avec le personnel de l’entreprise à préparer ces documents sans compter les réunions des comités d’Audit, de Ressources humaines, de Gouvernance et du conseil qui se pencheront sur diverses versions des mêmes documents ?

Encore une fois, pour quoi ? Pour qui ?

Pourquoi pas aux activistes de toutes origines ?

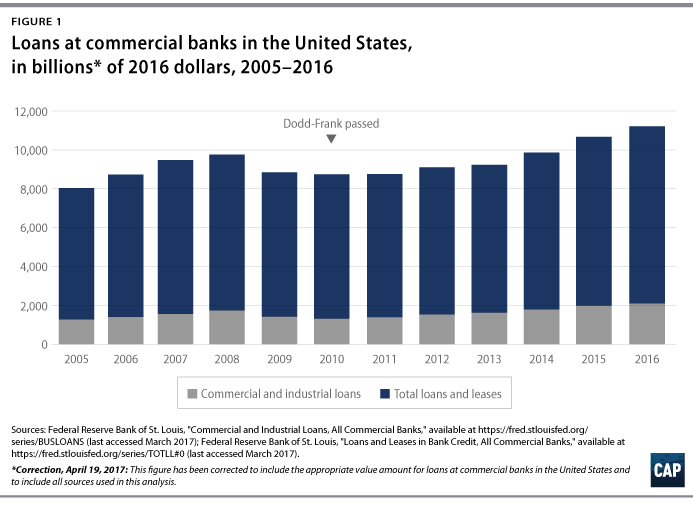

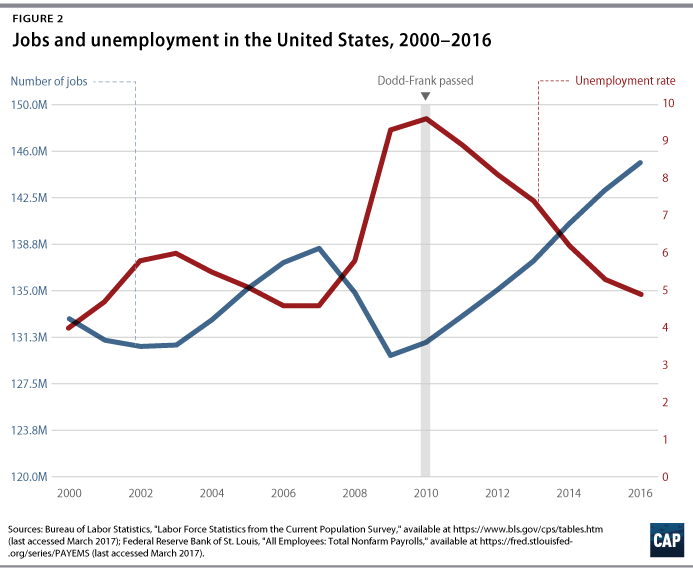

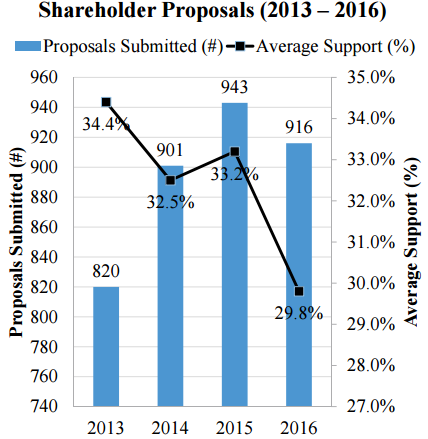

La dernière crise financière (2008/2009) semble avoir été l’accélérateur de l’activisme de groupes, autour des actionnaires, de même que l’arrivée d’experts de toutes sortes en gouvernance d’entreprise. Une industrie venait de naître! Le Rapport sur la gouvernance 2013, de Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg, s.e. n.c. r. l., soutient qu’il s’agit d’une tendance alimentée surtout « par le nombre accru d’occasions d’activisme découlant de certaines tendances actuelles de la législation et des pratiques à vouloir que plus de questions soient soumises à l’approbation des actionnaires » 4.

Mais, l’a-t-on oublié ? Les administrateurs ont un devoir de fiduciaire envers la société, pas juste envers les actionnaires. Ils doivent assurer la pérennité de l’entreprise et pas juste afficher un rendement à court terme qui entraîne des effets pervers sur la gestion des ressources humaines et ne tient pas suffisamment compte d’une saine gestion des risques. Question : est-ce que la mesure de l’efficacité consiste en une reddition de compte trimestrielle ? Est-ce que cette reddition de compte, toute formatée, n’est pas en train de remplacer la responsabilité et l’engagement personnel des hauts dirigeants ? La pression mise sur les conseils d’administration, par certains activistes (d’ailleurs pas toujours actionnaires de l’entreprise !), et de leurs conseillers divers, pour discuter avec le président du conseil et le président du comité de ressources humaines est perçue comme une tentative de la part de ces activistes d’imposer leur programme — au détriment des autres actionnaires et de l’intérêt même de l’émetteur. Et comme certains fournisseurs de ces activistes (agences de conseils en vote) produisent des analyses pour leur clientèle en vue d’une recommandation de vote lors d’une assemblée annuelle — cette démarche peut être interprétée comme une pression à la limite de l’intimidation.

Venons-en aux obligations de divulgation portant sur la rémunération des membres de la haute direction visés.

Les prêteurs, les actionnaires, ont le droit de connaître — à terme — les obligations de l’entreprise, y compris celles envers ses hauts dirigeants. Remarquez, ils ont aussi le droit de savoir s’il y a exagération ou abus. Mais, ont-ils besoin, entre autres, de connaître dans le détail les objectifs personnels fixés à Monsieur X ou à Madame Y?; pour quel % cela compte-t-il dans la rémunération incitative à court terme?; à quel % tels objectifs ont-ils été rencontrés?; pourquoi l’ont-ils été à ce %?. Peut-on sérieusement croire qu’une entreprise va publier que telle ou telle personne n’est pas à la hauteur, 12 à 15 mois après les faits?. Ou bien cette personne a rencontré les objectifs fixés de façon satisfaisante ou bien elle n’est plus là. Denis Desautels avance, dans le texte cité plus haut, qu’il « n’est pas sage d’appuyer les régimes de rémunération sur des formules trop quantitatives ou mathématiques et d’allouer une trop grande portion de la rémunération globale à la partie variable ou à risque de la rémunération ». Pourtant, les pressions ne cessent d’augmenter pour que cela soit le cas (Pay for Performance) et que ce soit basé sur des mesures objectives et connues comme le cours de l’action ou le résultat par action… le tout par rapport au groupe de référence. Performance devient le nouveau leitmotiv. S’est-on jamais demandé ce que cette divulgation pouvait avoir comme effet d’« emballement » sur la rémunération des hauts dirigeants? Et les politiques de rémunération doivent continuellement s’ajuster.

Le Règlement 51-102, à son Annexe A6 (Déclaration de la rémunération de la haute direction) prescrit non seulement le contenu, mais aussi la forme que doit prendre cette déclaration :

L’ensemble de la rémunération payée, payable, attribuée, octroyée, donnée ou fournie de quelque autre façon, directement ou indirectement, par la société ou une de ses filiales à chaque membre de la haute direction visé et chaque administrateur, à quelque titre que ce soit, notamment l’ensemble de la rémunération en vertu d’un plan ou non, les paiements directs ou indirects, la rétribution, les attributions d’ordre financier ou monétaire, les récompenses, les avantages, les cadeaux ou avantages indirects qui lui sont payés, payables, attribués, octroyés, donnés ou fournis de quelque autre façon pour les services rendus et à rendre, directement ou indirectement, à la société ou à une de ses filiales. (art. 1.3 par, 1 a).

L’émetteur assujetti doit, en outre, produire une analyse de la rémunération, laquelle doit :

1) Décrire et expliquer tous les éléments significatifs composant la rémunération attribuée, payée, payable aux membres de la haute direction visés, ou gagnée par ceux-ci, au cours du dernier exercice, notamment les suivants :

- a) les objectifs de tout programme de rémunération ou de toute stratégie en la matière ;

- b) ce que le programme de rémunération vise à récompenser ;

- c) chaque élément de la rémunération ;

- d) les motifs de paiement de chaque élément ;

- e) la façon dont le montant de chaque élément est fixé, en indiquant la formule, le cas échéant ;

- f) la façon dont chaque élément de la rémunération et les décisions de la société sur chacun cadrent avec les objectifs généraux en matière de rémunération et leur incidence sur les décisions concernant les autres éléments.

2) Le cas échéant, expliquer les actions posées, les politiques établies ou les décisions prises après la clôture du dernier exercice qui pourraient influencer la compréhension qu’aurait une personne raisonnable de la rémunération versée à un membre de la haute direction visé au cours du dernier exercice.

3) Le cas échéant, indiquer clairement la référence d’étalonnage établie et expliquer les éléments qui la composent, notamment les sociétés incluses dans le groupe de référence et les critères de sélection.

4) Le cas échéant, indiquer les objectifs de performance ou les conditions similaires qui sont fondés sur des mesures objectives et connues, comme le cours de l’action de la société ou le résultat par action. Il est possible de décrire les objectifs de performance ou les conditions similaires qui sont subjectifs sans indiquer de mesure précise.

Si les objectifs de performance ou les conditions similaires publiés ne sont pas des mesures financières conformes aux PCGR, en expliquer la méthode de calcul à partir des états financiers de la société.

Et le tout dans un langage clair, concis et « présenté de façon à permettre à une personne raisonnable, faisant des efforts raisonnables de comprendre (…)

- a) la façon dont sont prises les décisions concernant la rémunération des membres de la haute direction visés et des administrateurs ;

- b) le lien précis entre la rémunération des membres de la haute direction visés et des administrateurs et la gestion et la gouvernance de la société (par. 10). »

L’Instruction générale relative au règlement 51-102 sur les obligations d’information continue définit, en son article 1.5, ce qu’il faut entendre par langage simple. C’est en quatorze points ; je vous en fais grâce. Je rappelle ici qu’une instruction générale est réputée constituer un règlement.

Trop, c’est comme pas assez. C’est aussi ce que pourrait se dire la personne raisonnable après avoir fait des efforts raisonnables pour comprendre tout cela. Cette personne pour laquelle l’entreprise publie toutes les informations réclamées par le législateur/autorité réglementaire poussé par l’industrie de la gouvernance qui, elle, bénéficie de la complexification des règles.

L’émetteur est placé devant ces obligations auxquelles il veut bien se conformer, mais pas au point de livrer des éléments importants de ses stratégies de développement au premier lecteur venu. Ce qui pourrait même être contre l’intérêt des actionnaires, et finalement ne bénéficier qu’à la concurrence. Ce qui fait que l’on en est rendu à se demander comment éviter de divulguer « les secrets de familles », si je puis dire, sans indisposer les autorités réglementaires — surtout si on doit aller au marché dans les mois qui suivent.

Malaise !

Si mon souvenir est bon, les pressions sont venues de groupes divers (investisseurs institutionnels, gestionnaires de fonds et autres) qui jugeaient les rémunérations des hauts dirigeants extravagantes et non méritées. Pour eux, les administrateurs étaient responsables de cet état de fait. Alors, on a légiféré, réglementé, permis le Say on Pay et diverses propositions d’actionnaires. La rémunération a-t-elle baissé ? Non. Les parachutes ont-ils disparu? Non. Chacun se compare à l’autre et ne voit pas pourquoi il ne serait pas rémunéré comme son vis-à-vis de l’entreprise Z. Et les PDG de se négocier un contrat blindé — pourquoi pas? Ils sont assis sur un siège éjectable.

Ne pourrait-on pas se demander maintenant si partie ou toutes ces exigences ne produisent pas davantage d’effets pervers que de bénéfices ? (Dans le plan d’affaires 2013-2016 des ACVM. Les deux dernières priorités sont : réglementation des marchés ; et efficacité des mesures d’application de la loi).

Ne pourrait-on pas aussi se demander si exiger une durée minimale de détention de l’actionnariat pour obtenir le droit de vote à une assemblée générale ne serait pas souhaitable ?

Si publier les résultats deux fois l’an, au lieu de quatre, ne donnerait pas un peu d’oxygène aux entreprises — un début de délivrance de la tyrannie du rendement à court terme ? Et, quant à y être, pourquoi continuer de publier l’information telle qu’exigée, si elle n’est pas lue ?

Et puis, à quoi servent les administrateurs si les actionnaires peuvent s’immiscer dans la gestion d’une entreprise et imposer leurs volontés en tout temps ?

Et à quel actionnaire permettre quoi ? Un Hedge Fund qui achète et vend des millions d’actions par minute ? Un fond mutuel qui garde des actions quelques années ? Un retraité qui conserve ses actions depuis 20 ans ?

D’ici à ce que l’on ait réfléchi à tout cela, ne peut-on pas marquer le pas ?

- 1. Allaire, Yvan, Pourquoi cette vague de privatisation d’entreprises cotées en Bourse, La Presse, mars 2007.

- 2. Desautels, Denis, OC, FCA, Les défis les plus difficiles des administrateurs de sociétés, Collège des administrateurs de sociétés, Conférence annuelle, 11 mars 2009.

- 3. Carol Liao, A Canadian Model of Corporate Governance, Where do shareholders really stand? Director Journal, January/February 2014, p. 37

- 4. p. 55.

*Nicolle Forget siège au conseil d’administration du Groupe Jean Coutu (PJC) Inc., de Valener Inc. et de ses filiales et du Collège des administrateurs de sociétés. Elle a, entre autres, fait partie d’un comité d’éthique de la recherche et des nouvelles technologies et de comités d’éthique clinique, de même que du Groupe de travail sur l’éthique, la probité et l’intégrité des administrateurs publics et a présidé le Groupe de travail sur les difficultés d’accès au financement pour les femmes entrepreneuses.

Madame Forget a été chargée de cours à l’École des Hautes Études commerciales et elle est l’auteure de cas en gestion de même que de quelques ouvrages biographiques. Madame Forget a d’abord fait du journalisme à Joliette avant de se consacrer à la gestion d’organismes de recherche et de formation durant les années 1970. Elle a aussi été membre (juge administratif) de tribunaux administratif et quasi judiciaire durant les années 1980 et 1990.

Madame Forget est diplômée de l’UQÀM (brevet d’enseignement spécialisé en administration), des HEC (baccalauréat en sciences commerciales) et de l’Université de Montréal (licence en droit et DESS en bioéthique). Elle fût membre du Barreau du Québec jusqu’en 2011.

Madame Forget a siégé à de nombreux conseils d’administration dont : Fédération des femmes du Québec, Conseil économique du Canada, SEBJ, Hydro-Québec, Hydro-Québec International, Gaz Métro Inc., Agence québécoise de valorisation industrielle de la recherche, Fonds de solidarité des travailleurs du Québec, Université de Montréal, École polytechnique, Innotermodal. Elle a, de plus, présidé les conseils de Accesum Inc., Nouveler Inc., Accès 51, Ballet Eddy Toussaint, Festival d’été de Lanaudière et Association des consommateurs du Québec.