Cet article présente les comparaisons des programmes de rémunération des administrateurs de sociétés en fonctions des types d’organisations suivants :

À ma connaissance, l’étude de Reda est la plus complète sur le sujet.

The pay levels and mechanisms for directors at public companies are well studied and benchmarked. Private and family-owned companies? Not so much. Indeed, board compensation norms for these non-public firms (which make up a huge segment of our economy) have long been very obscure. New research sheds light on the topic.

Private companies continue to struggle with how much to pay their outside board members given the shortage of available benchmarks and data. Unlike publicly traded companies, where detailed information about director compensation can be collected from an annual proxy statement and multiple survey sources, understanding pay at private boards requires further research and analysis.

Even among private companies, the variety of company ownership structures must be considered. For example, how does director compensation at a family-owned company compare to a company that is private equity-owned?

After significant growth in the early 2000s, increases in public company board pay levels have now stabilized. Heightened scrutiny from shareholders and a series of high-profile lawsuits have resulted in a standardization of pay levels between companies of similar size and industry. Companies are reviewing their plans more frequently than ever before and, subsequently, are making smaller changes.

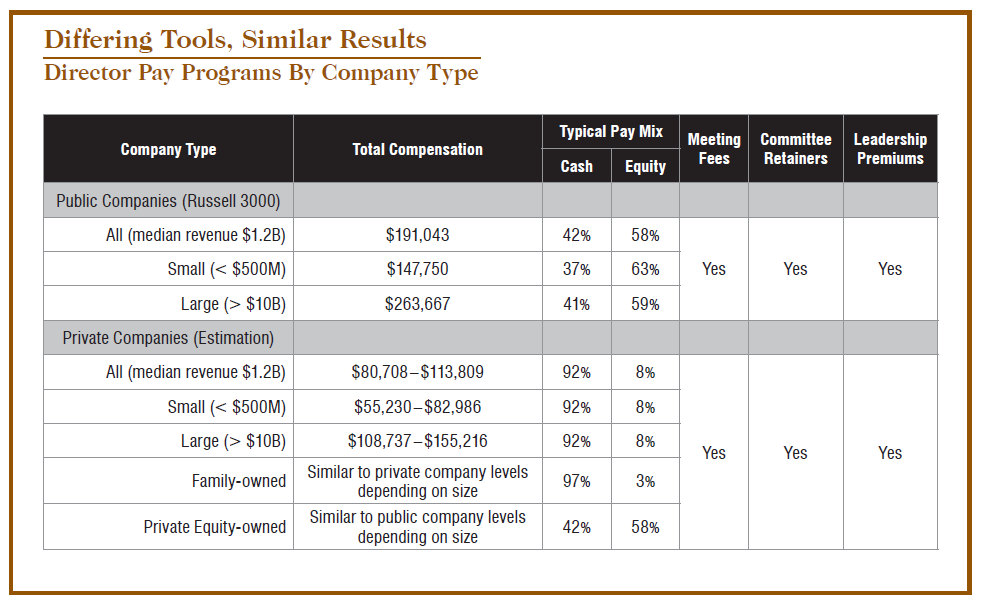

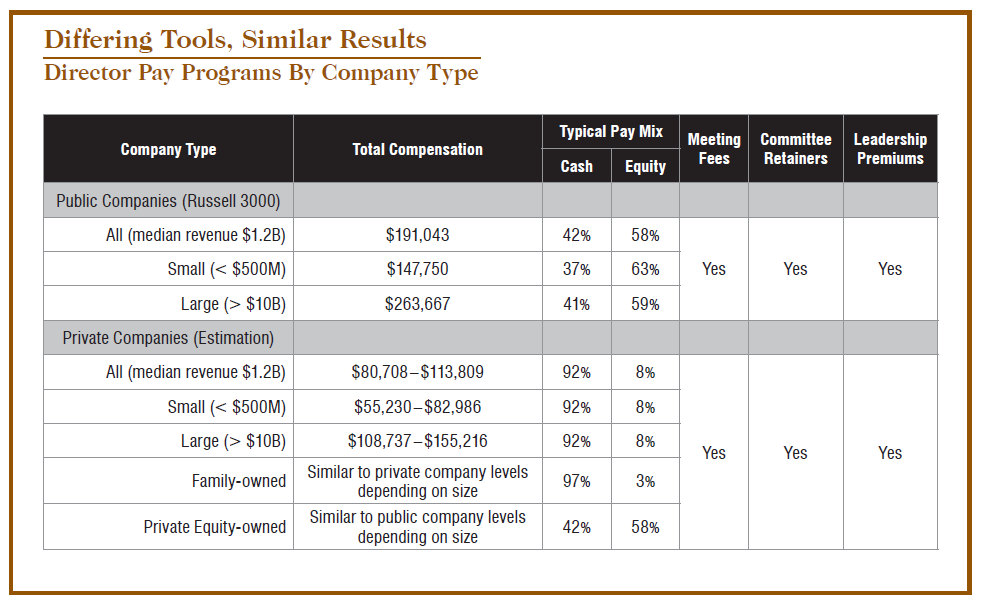

This post compares and contrasts director pay programs at public firms that are owned by large institutional and private investors with programs at various types of private companies, as follows:

1. General

Owned by one person or a small group with a goal of increasing long-term shareholder value.

2. Family-owned

Owned by family members who have an interest in building long-term shareholder value to pass onto the next generation.

3. Private equity-owned

Owned or sponsored by private equity (PE) firms.

Private companies tend to organize their boards along the lines of public corporations. Many private companies are contemplating public status, and are working to attract investors who are more comfortable with a well-developed corporate governance structure. To staff the board with its numerous committees and leadership roles, competitive pay is required to attract and retain qualified directors.

Public and private companies compete for the same outside board talent. Private companies assume most of the leading practices of public firms with regard to board pay.

For organizations of all kinds, good governance starts with the board of directors. Despite the differences in director pay practices, boards have similar overall objectives. While the role of a board will evolve as a company grows and matures, the underlying principles remain consistent. The oversight duty, the decision-making authority, and the fiduciary responsibilities of a board are comparable, regardless of ownership, industry, size, complexity, or location within the U.S.

Public and private companies compete for the same outside board talent. The confluence of director service has made pay practices of private companies more competitive with public ones. Private companies continue to assume most of the leading practices of public firms with regard to board pay.

Despite the implementation of cash-based outside director pay plans that mirror public companies, private companies do not generally award equity, but sometimes partially make up this value in higher cash compensation. Since equity makes up a large portion of total pay for public company directors (generally over 50 percent), total director pay at private companies is significantly lower than at public companies.

Cash compensation paid to outside directors of public and private companies is fairly similar in terms of both value and structure. Cash retainer values are consistent among both public and private companies, and increase with company size.

Like public companies, many private ones pay additional cash retainers to committee chairs and members, and provide some type of incremental cash award to the lead director or non-executive chair. Private companies are also following the public company trend of eliminating board and committee meeting fees, and making up for this with a corresponding increase in board and/or committee member retainers.

Additional compensation is almost always paid for serving as a committee chair, lead director, or non-executive chair.

Public companies

For publicly held companies, many of the board’s responsibilities are defined by regulatory bodies. These are more rigorous and complex than for privately held firms where there is a substantial amount of discretion as to the role a board will play.

It has always been desirable to have a healthy complement of outside directors on the board. Corporate governance rules adopted by the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the NASDAQ Stock Market (NASDAQ) in 2003 require that a majority of a listed company’s board consist of independent directors, and with limited exceptions, that the board appoints independent compensation, audit and nominating/corporate governance committees. With the need for independent directors comes a price.

Among the 1,813 companies in our firm’s study of director pay programs among Russell 3000 companies, median 2015 total director compensation was $191,043. The median revenue of these companies was $1.2 billion. Total compensation increased with company size.

Most public company directors receive a combination of cash and equity compensation, with equity making up at least half of total pay regardless of company size or industry. The median pay mix of companies studied was 58 percent equity and 42 percent cash.

The median annual board cash retainer was $55,000. Cash retainers are correlated with company size, increasing from a median of $40,000 to $100,000 by ascending revenue size.

Additional compensation is almost always paid for serving as a committee chair, lead director, or non-executive chair. Increasingly, these leadership premiums are the only additional amounts beyond the board and committee retainers and equity awards paid in these more streamlined director pay programs.

Almost all companies (94 percent) provided committee chair retainers, consistent with the general industry practice of providing premium pay to the directors with the most responsibility. Just under half of all companies (47 percent) pay committee member retainers.

Of all companies in our study, 41 percent reported a non-executive chair (NEC). Most of these (91 percent) provided additional pay, with the median added fee for this leadership position being $65,000. Fifty-three percent of all companies reported a lead director. Of these, 79 percent provided additional compensation, a median of $25,000 (almost entirely paid in cash). Unlike the NEC role, the added pay for this role did not vary significantly by company size or industry.

For annual equity awards, which typically make up at least half of total pay, the market trend over the last decade has been away from stock options and toward full value shares (restricted stock, deferred stock or outright stock). The prevalence of options continues to decline, and when companies do grant them, they often grant options along with full value shares.

The median total equity award for the entire study sample was $112,000. Nearly all companies studied provided equity (97 percent). Seventy-seven percent granted full value shares only, compared to just eight percent granting stock options only. Twelve percent of companies granted a mix of full value shares and stock options, and the remaining three percent of companies granted no equity awards at all.

Private companies

No longer able to afford the informal corporate governance practices of the past, private companies are under increasing pressure to implement or improve board oversight. These companies are embracing public-company governance, including formation of boards that include outside directors and standard committees. This movement has also affected family businesses, particularly as shareholders of family-run companies have become less concentrated with each passing generation.

The bar has thus been rising for private company governance, despite the fact that requirements imposed by various governing bodies apply only to public companies. In today’s business environment, the talent pool is becoming more homogeneous as executives and directors move freely between organizations that are small and large, and public and private.

We have estimated total director pay levels for private companies of various sizes, based on our consulting experience as well as our Russell 3000 study of director pay programs at public companies. Among all revenue categories, more than 50 percent of total pay was made up of equity. Using this data as a guide, we have estimated the total pay range for similarly sized private companies, as follows:

The low end of private company total pay range represents the cash portion of public company total pay for the applicable revenue category.

The high end of private company pay range represents the cash portion of public company total pay, plus 30 percent of the equity portion for the applicable revenue category.

For example, the enclosed table shows that, among all Russell 3000 companies, total pay is $191,043, made up of 42 percent cash and 58 percent equity. Among similarly sized private companies, total compensation will range from $80,708 (the 42 percent cash portion of $191,043) to $113,809 (the 42 percent cash portion of $191,043 plus 30 percent of the remaining equity).

Thus, the resulting private company pay range equals 42 percent to 60 percent of public company pay for similarly sized companies. We have followed the same methodology to estimate total pay levels among private companies within each revenue category.

Private companies pay directors cash to the same extent as public companies of similar size, and in some cases more to make up for the lack of equity.

Based on our experience working with private companies, we believe that these ranges are a sound benchmark for how private companies of various sizes pay directors. In general, these companies pay cash to the same extent as public companies of similar size, and in some cases pay more cash to make up for the lack of equity awards (though still at a reduced rate, resulting in lower total pay).

Most public companies have some kind of executive equity program in place, and equity typically represents 50 percent to 75 percent of total pay for their senior executives. While more private companies are adopting long-term cash incentive plans, real equity awards (stock options or restricted stock) are used by a minority of private companies.

Overall, we estimate that less than 10 percent of private companies provide director equity awards, compared to 97 percent of public companies as mentioned previously. An exception to this is PE-owned companies.

Family-owned companies

Most family businesses benefit from a board that includes not only family members but also well-informed, seasoned, outside directors. These independents bring outside knowledge, leadership development skills and accountability. Leadership development is particularly important as there must be a management succession plan that includes family and non-family members, if necessary.

In 2016, Gallagher’s research team set out to understand exactly how much outside directors of family-owned companies are paid by conducting phone and electronic mail inquiries to a number of large family-held business. The outreach was successful, with nineteen companies responding. These companies spanned various industries, including retail, food processing, consumer products and general manufacturing. The median revenue of these nineteen companies was $6.9 billion.

Outside directors of family-owned companies are paid similarly to directors of other private companies, with a focus on cash and little to no equity

Twelve of the nineteen companies (63 percent) had family members that were also senior members of the management team serving on the board. In line with common practices for all types of companies, these family members received no compensation for board service.

We found that outside directors of family-owned companies are paid similarly to directors of other private companies, with a focus on cash and little to no equity awards. Some major findings:

1. The median annual cash retainer was $75,000. Median annual total compensation was $100,250. Only 11 percent of companies used equity as part of their director pay package.

2. Forty-two percent of companies paid a lead director premium.

3. Forty-seven percent paid their committee chairs a leadership premium.

4. Forty-two percent paid board meeting fees, with a range of $1,958 to $2,650 per meeting.

5. Thirty-two percent paid committee meeting fees with a range of $1,531 to $2,294 per committee meeting.

Like non-family-owned private companies, cash levels are similar to what we would expect to see among public companies. In fact, our Russell 3000 study found that public companies with revenues ranging from $3 to $9.9 billion also had a median cash retainer of $75,000.

Consistent with expectations, the lack of equity awards (present at only 11 percent of our family-owned company sample) creates a large disparity in total pay compared to the same group of Russell 3000 companies ($3 to $9.9 billion in revenue). The median compensation among public companies was $227,005 (consisting of 57 percent equity and 43 percent cash). This is 126 percent higher than the $100,250 seen among the family-owned sample.

This difference is due to the equity award. If we were to extricate only the 43 percent cash portion of $227,005, the resulting $98,000 (inclusive of cash retainer and committee member fees) is right in line with the total of $100,250 at family-owned companies. As discussed previously, this is one way that private companies, family-owned or not, set director pay—by stripping out the equity portion of comparable public company pay.

Private equity owned or sponsored companies

PE-owned companies invest in strong board governance early on in pursuit of significant growth. A top-down agenda set by the private equity fund generally drives the board’s focus, with an overall goal of progress toward a liquidity event, such as an initial public offering or M&A event.

The directors of PE-owned companies are mainly focused on strategies to increase investor value, with a much shorter time horizon than directors of private or public companies. Accordingly, these PE-owned boards are more deeply entrenched with company management, and in most cases meet more frequently than other company boards.

Beyond employee directors, there are two types of directors that will typically serve on these boards: outside directors, and employees of the private equity firm, which we refer to as “PE principals.”

Outside directors

Outsiders are often introduced to the board by the private equity firm that owns the portfolio company. Bringing in a director with no affiliation to the company or PE firm is most often made with the goal of gaining the benefit of that person’s specific qualifications and expertise.

These outside directors are generally paid by the PE fund owner, and pay is similar to publicly traded company directors. Unlike other private companies, where the focus is on cash, these outside directors generally receive a mix of both cash and equity compensation. In many cases, the focus is on equity.

PE principals.

Private equity firms exercise control over portfolio companies through their representation on the companies’ boards. These PE principal directors have a strong sense of personal ownership that is ensured by the compensation arrangements (particularly in the form of “carried interest”) of their firms.

PE principals are either paid nothing, or the same as the outside directors. In the latter arrangement, they are getting paid by both the portfolio company to be a director and by the private equity firm as an employee, which can result in excessive payment levels. For this reason, these “double pay” arrangements have sometimes caused controversy.

In summary, there are real differences in director pay between public and private companies, with the exception of private-equity controlled companies that tend to pay the same as public company counterparts.

Similar to executive pay, director pay trends continue to “trickle down” from public companies to private companies. With evolving standards and further integration of the director talent pool, we expect that private companies will continue adopting the cash-based pay practices of public companies. For all companies, governance improvements are focused on strengthening the role and responsibilities of the board of directors, and an appropriate director pay plan is a key factor to consider.