Voici un article très bien documenté sur la recrudescence de l’activisme des actionnaires en Europe.

L’actif sous contrôle des activistes européens est passé de 21,7 B $, en 2012, à 27,5 B $, en 2015.

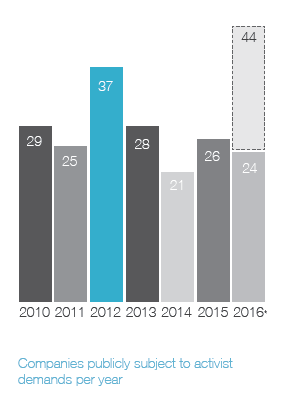

The inaugural edition of this report, published nearly two years ago, suggested that so long as opportunities presented themselves, activists would continue to seek governance, strategy and capital allocation reforms from European issuers. Indeed they have. After ebbing briefly in 2014, when only 51 companies were publicly targeted (after 61 in 2012 and 59 in 2013), activism has roared back, with 67 companies targeted in 2015 and 64 in the first half of 2016 alone. Assets under management for European activists have grown slowly in that period—from $21.7 billion in 2012 to $27.5 billion in 2015—suggesting the growth has been funded by new entrants and foreign players.

Even publicity-shy activists who have been working with companies behind closed doors for many years concede that the growth in activism in Europe is accelerating. Some see a cyclical boom, with activists hoping to catalyse M&A. Yet on topics such as remuneration, and with the launch of specialist European activist funds, the change appears built to last. Part of the evolution of activism in Europe has been the success of tactics seen as more common in the U.S., including proxy contests. Although longer-term participants and the bulk of campaigns suggest lowkey, collaborative approaches are still more common, activists are becoming less shy about testing where the boundaries lie.

Even publicity-shy activists who have been working with companies behind closed doors for many years concede that the growth in activism in Europe is accelerating. Some see a cyclical boom, with activists hoping to catalyse M&A. Yet on topics such as remuneration, and with the launch of specialist European activist funds, the change appears built to last. Part of the evolution of activism in Europe has been the success of tactics seen as more common in the U.S., including proxy contests. Although longer-term participants and the bulk of campaigns suggest lowkey, collaborative approaches are still more common, activists are becoming less shy about testing where the boundaries lie.

The five countries covered in detail in this post represent approximately 80% of the companies targeted by activists since 2010, although in the past two-and-a-half years the level has been lower. Outside of their ranks, Scandinavia and the Netherlands are popular hunting grounds, while Southeastern Asset Management picked up a board seat at Spain’s Applus in July.

Future editions of this report will have to find a different flag for the front cover, following the U.K.’s decision to leave the European Union. The impact on activism in Europe could be still more profound. In the short period since the referendum, stock markets all over Europe dipped temporarily, creating buying opportunities at export-led companies. Elliott Management, a U.S. hedge fund with a well-established London office, has disclosed four positions since the vote (although it held some as toe-holds previously). Some of these companies were already subject to takeover offers, and Elliott has agitated for higher bids.

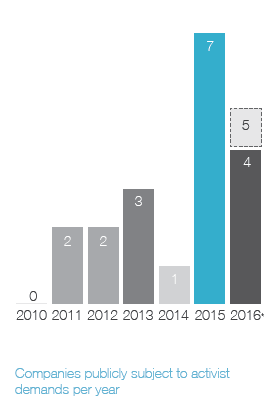

Another development, albeit not directly connected with traditional forms of activism, is the rise of activist short selling, where investors bet against a company and attempt to convince investors the stock price will drop. Such campaigns more than doubled from 2014 to 2015, and gained prominence after fuelling sell-offs at the likes of Quindell and Wirecard. Already in the first half of 2016, six companies had been targeted.

The U.S. has seen activism spread beyond a disciplined asset class in recent years. Whether European investors prove to be quite as demanding remains to be seen. But if markets continue to be volatile, opportunities for value investors, arbitrageurs and short sellers will be more plentiful. Recent events suggest there will be opportunists to match.

United Kingdom

Activism has roared back to prominence in the United Kingdom since 2014, with three high-profile proxy battles and the first FTSE 100 company accepting an activist into its boardroom.

ValueAct Capital Partners, a San Francisco-based hedge fund known for its engagements with Adobe and Microsoft, prefers to be seen as a cooperative investor. It generally avoids aggressive tactics such as proxy fights, lawsuits and public letter-writing, preferring testimonials from CEOs it has worked with in the past. Investing in Rolls-Royce Holdings, with its strategically important submarine business and stately shareholders, required a display of deference. As well as hiking its stake to above 10%, the fund worked with new CEO Warren East for over 200 days before its nominee was offered a board seat.

Others have taken less conciliatory paths. Sherborne Investors, defeated in a 2014 proxy contest at Electra Private Equity, raised its stake to 30% before finally winning two board seats the following year. Since then, almost all the other directors have been forced out, and the fund’s external manager served notice. Smoother contests saw victories for Elliott Management at Alliance Trust and the family office of Luis Amaral at Stock Spirits. Yet whereas the former has reformed slowly, attracting potential suitors in the process, the latter has descended into acrimony. The Stock Spirits board may have promised not to engage in acquisitions and to pay a special dividend, but risked conflict by designating the activist nominees non-independent.

Strong shareholder rights, including the ability to call a meeting with just 5% of shares, and a highly liquid and dispersed market, should mean the U.K. continues to be a focal point for activism in Europe. With stocks initially down sharply after the country voted to leave the European Union, a few bargain-hunters may even be preparing campaigns.

Proxy fights have become increasingly common at U.K. companies, with activists claiming a better record of success than in previous years after the Alliance Trust watershed. Toscafund, fighting the first in its 16-year history, will hope that track record continues. Elliott Management has also made merger arbitrage central to its strategy in recent years. Although operational activist Cevian Capital appears to be more focused on Continental Europe, turnarounds at exporters Rolls-Royce Holdings and Meggit are attracting activist attention.

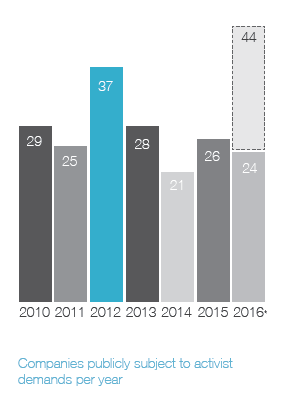

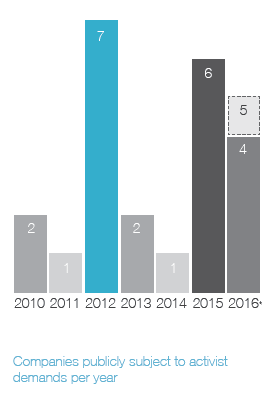

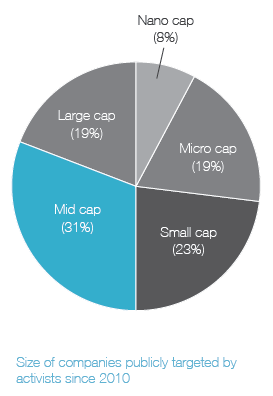

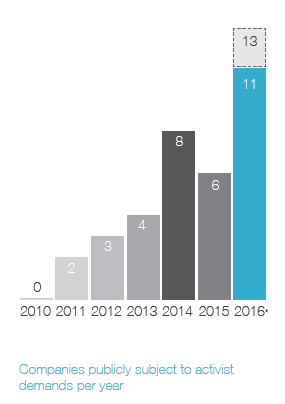

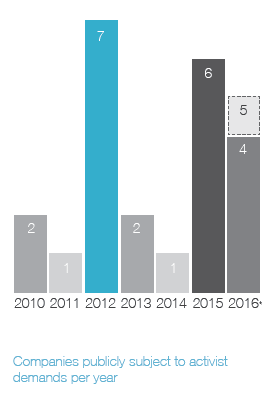

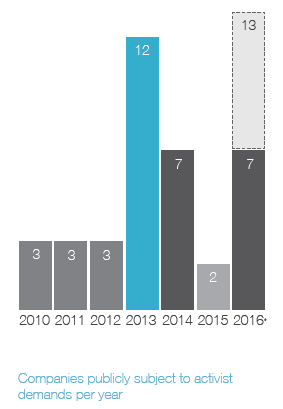

Activism in the U.K. increased steadily after the financial crisis, culminating in the shareholder spring of 2012. Despite a dip thereafter, 2015 and 2016 have seen steadily more activity and this year is expected to be the busiest year yet.

* as of 30th June 2016. Projected full-year figure shown in dotted box.

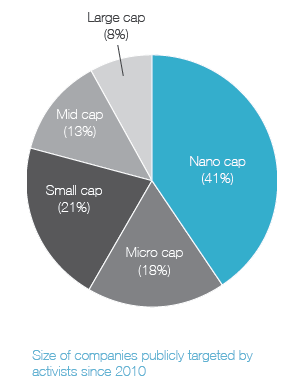

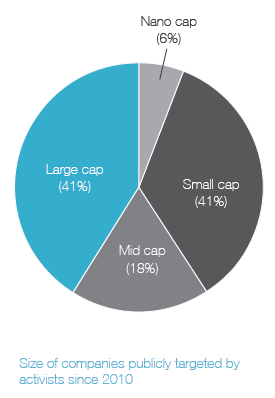

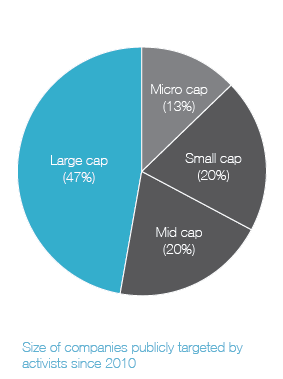

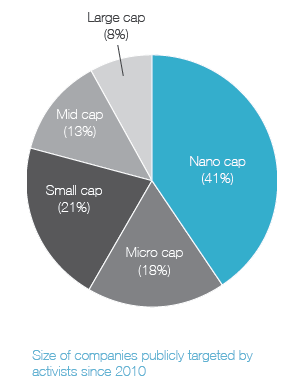

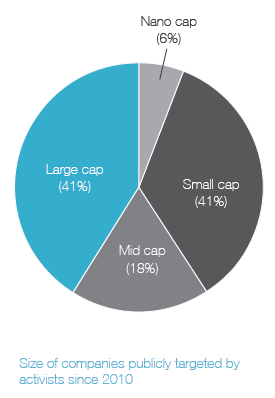

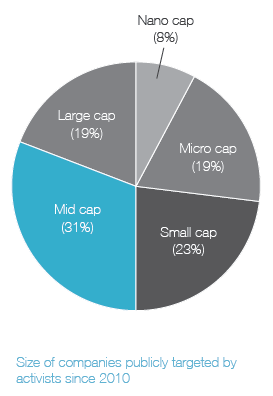

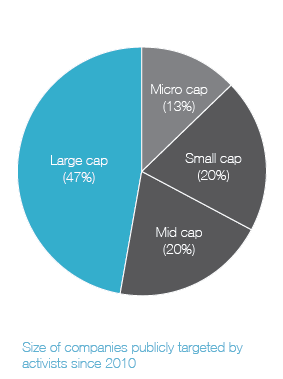

Easy access to shareholder rights, including meeting requisitions and proposals ensure that smaller companies are always vulnerable to activism. With several well funded and established activists setting up in London, however, large cap companies are starting to draw more attention.

Shareholder Activism—recent developments in the U.K.

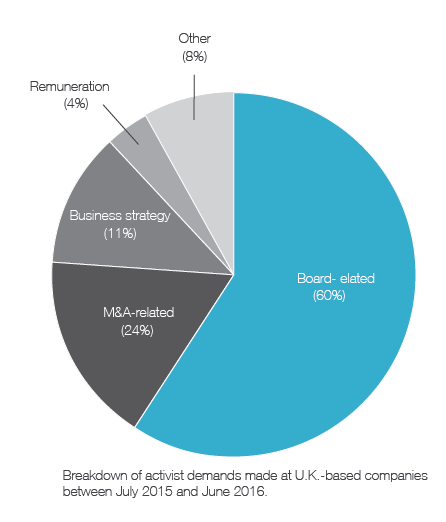

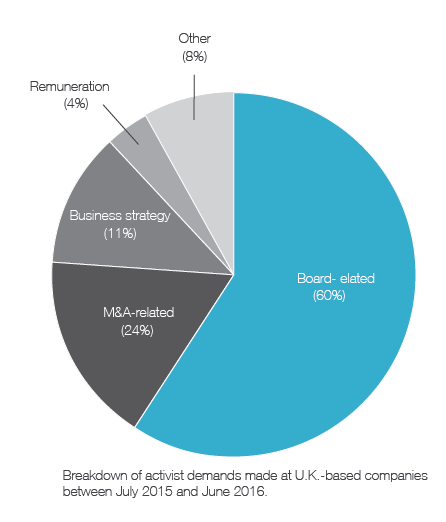

Continuing the trend of previous years, the U.K. continues to see the lion’s share of activism in Europe. Over the last 12 months, approximately 43% of all European campaigns were played out in the U.K., according to Activist Insight data. Whilst the traditional mix of activist strategies were deployed, attempts to obtain board representation received most attention and generated most success.

In April 2015, Elliott Management’s criticism of Alliance Trust’s poor performance and high costs resulted in two new non-executive directors (“NED”) being appointed to the latter’s board. At Stock Spirits, Western Gate Private Investment’s (“WGPI”) complaints of “spiraling costs” and a board prone to “group-think” also resulted in the appointment of two NEDs following a shareholder vote. At Rolls- Royce Holdings, too, ValueAct Capital’s complaints regarding a fifth profit warning in two years resulted in a NED appointment for ValueAct’s chief operating officer in return for the promise that ValueAct would not lobby for a break-up of the company, nor increase its stake above 12.5%.

In each of these cases, the activists’ public rationale for supporting NED appointments has been to better long-term results through improved corporate governance and executive scrutiny. Also notable is that in two of the cases mentioned above, new appointments were subject to negotiation and compromise, with the activists accepting limitations on the extent of their directors’ participation in board meetings and board committees.

Board appointments have not gone without criticism, however, particularly regarding the perceived lack of independence of the new directors. Certainly, fears over conflicts of interest can have practical implications. In the case of Rolls-Royce,

ValueAct’s seat on the board was subject to limited rights: it has no ability to propose changes in strategy or management, call a shareholder meeting nor push for mergers or acquisitions. At Stock Spirits, the new NEDs have been prevented from sitting on certain committees and the chairman has publicly stated that they may be asked to leave meetings where commercially sensitive information, such as pricing, is discussed.

The U.K.’s legal, regulatory and political landscape remains supportive of shareholder engagement, and activists will leverage this to reinforce their (shorterterm) theses. Witness the increasing activity of Investor Forum (the “Forum”), whose 40 members own approximately 42% of the FTSE All Share Index. The Forum seeks to promote long-term investment and collective engagement with U.K. companies by its members. In August, after over a year of private engagement with Sports Direct alongside major institutions holding approximately 12% of Sports Direct, the Forum issued a press release calling for a comprehensive and independent review of corporate governance at the company.

Whilst the mechanics for investor engagement have remained largely constant over the last few years in the U.K., the grounds for activist shareholders to demand change remains dynamic. In addition to the traditional activist calling cards of under-par growth, over-inflated executive salaries and deficiencies in corporate governance, Britain’s recent referendum vote to leave the European Union may lead to some boards being challenged on their strategies to cope with Brexit. For so long as activists can continue to find intrinsic, unlocked value in U.K. companies, the facilitative environment and dynamic business conditions will continue to catalyse activism in the U.K.

France

Controlling shareholders, double voting rights and government stakes in key industries make activism a challenging proposition in France, though there is no sign of activists abandoning their ambitions altogether. Last year, Airbus quietly sold its stake in Dassault Aviation in order to buyback shares, a year after The Children’s Investment Fund suggested the move.

Admittedly, not all activists have had such success. Elliott Management is currently in a legal battle with XPO Logistics Europe (formerly Norbert Dentressangle). Although it failed to remove CEO Troy Cooper at this year’s annual meeting, it owns enough to prevent the U.S. parent from delisting the company. In 2015, U.S.-based P. Schoenfeld Asset Management (“PSAM”) acquired a small stake in Vivendi and suggested selling Universal Music Group in order to pay larger dividends. Vivendi Chairman Vincent Bolloré increased his stake and pushed through double voting rights for long-term investors, enhancing his control.

Nonetheless, activism has begun to thrive in France. Electrical parts company Rexel waved goodbye to its CEO just months after Cevian Capital disclosed a stake earlier this year, Carrefour faced another request for board seats, and a merger between Maurel & Prom and MPI saw opposition from U.K. and South African funds. Meanwhile, the Paris-based hedge fund CI-AM has been making a name for itself, attempting to use the courts to stop the takeover of Club Med by China Fosun International and to reshape a licensing agreement between Euro Disney and The Walt Disney Company, to ensure investors in the Paris theme park were adequately compensated.

Activist short selling is also making its presence felt. In December, Muddy Waters Research released a 22-page report on grocery chain Groupe Casino, which it said was “dangerously leveraged, and… managed for the very short term.” Shares were down 11.6% a week after the report was published.

Elliott has already been holding out at Norbert Dentressangle for more than a year, preventing the company from delisting following a takeover bid by XPO Logistics. An attempt to take the chairman role from CEO Troy Cooper at this year’s annual meeting failed, but the company has yet to be delisted–unlike MPI, which has now been merged with Maurel & Prom. Vincent Bolloré shows no signs being slowed down by U.S. activists such as P. Schoenfeld Asset Management, which won dividends but no seat on the board from a 2015 raid. In December, Muddy Waters Research released a much discussed short report on grocer Groupe Casino.

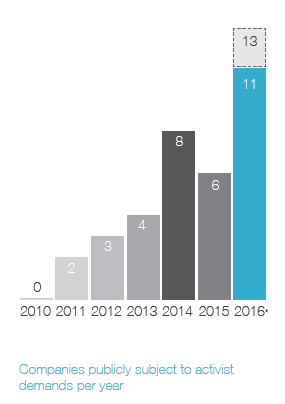

2015 saw a sudden renewal of activist interest in France, coming close to the peak of 2012. So far, 2016 is off to a reasonable start, although it seems the country will continue to be targeted intermittently.

* as of 30th June 2016. Projected full-year figure shown in dotted box.

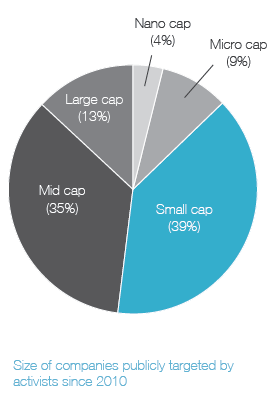

Activist targets tend to be larger, on average, in France than in other countries, perhaps because they are more likely to be susceptible to international pressure. However, a rising number of campaigns at small cap companies may presage a busier market in future.

France is in the process of strengthening its Say on Pay

The emergence of shareholder activism in France over the last decade has been supported by the development of corporate governance rules and best practices. A number of campaigns following the global financial crisis focused on corporate governance, including the separation of chairmen and CEO roles, management performance and compensation.

Say on Pay was introduced in France in 2013 in the form of a soft law set forth in the corporate governance code applicable to French listed companies (the “AFEP-MEDEF Code”). France opted for an annual non-binding shareholder vote on all forms of compensation paid or granted to the company’s officers, including the chairman (vote consultatif des actionnaires). If compensation is rejected, a board is required to post a release on the company’s website following its next board meeting detailing how it intends to deal with such vote.

As the vote is non-binding, the general view until now is that boards may maintain compensation granted to the company’s officers, even when it is rejected by shareholders, or receives very limited support. In 2016, Renault and Alstom’s CEO compensation gave rise to a negative Say on Pay vote by shareholders. In the case of Renault, the board met immediately after the meeting and decided to confirm the 2015 compensation of the company’s CEO, generating criticism from the French state, which holds a significant stake in Renault, and politicians, as well as questions on the efficacy of French Say on Pay.

Following the Renault controversy, a public consultation was launched in order to, amongst other things, strengthen the Code’s Say on Pay provisions. The proposed new wording (likely to be in force from September 2016), is somewhat more restrictive than that currently in force, as it contemplates an express obligation for the board to amend the relevant officers’ compensation for the previous year or the company’s management compensation policy for the future. The French government also proposed in early June in a bill currently under discussion at the French Parliament (the “Loi Sapin II”) to introduce a binding Say on Pay in the French Commercial Code. This bill was highly debated and, at the date hereof, the French Assemblée Nationale and Sénat have taken different positions on this topic.

In the context of this reform, it is essential that French legislators bear in mind that the board has always been and shall remain the competent corporate body to fix the compensation granted to the company’s officers. In particular, the board is the sole corporate body which can set the applicable performance criteria for the annual and long-term variable remuneration of the company’s officers and assess whether or not these criteria have been met. In our view, the best way to achieve a well-balanced system would be to implement a Say on Pay inspired by the U.K. model, with (i) a binding shareholder vote every three or four years on the company’s compensation policy, and (ii) a nonbinding shareholder vote every year on the compensation granted to the company’s officers for the previous fiscal year, without any effect provided that such compensation complies with the management compensation policy approved by the shareholders.

Germany

Shareholders have always occupied a more complicated role in Germany, where a two-tier board structure gives labour unions and other interest groups a role, while limiting direct contact with executives.

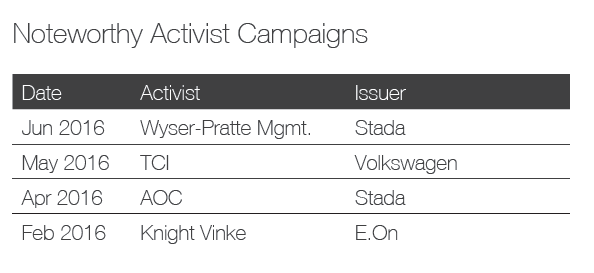

In recent years, however, activists have descended on Germany. Knight Vinke, a Monaco-based hedge fund that specialises in large cap companies, has written a white paper on how E.On should be reshaped, while Cevian Capital has stakes in Bilfinger and ThyssenKrupp, where it is practising its traditional long-term, operational style of activism. Sports retailer Adidas has been forced to deny suggestions that Southeastern Asset Management was behind a decision to sell its golf division.

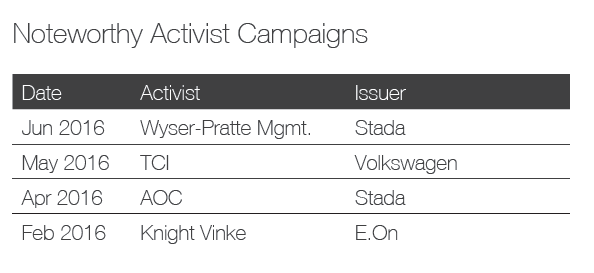

Events at Volkswagen since the emissions scandal highlight both the opportunities and the challenges for activism in Germany. London-based hedge fund The Children’s Investment Fund (“TCI”), wrote a scathing public letter in May, attacking executive compensation and deals with local state officials and unions that had damaged productivity levels.

Other investors sought to use Volkswagen’s annual meeting to send a message by attempting to deny management board members discharge from liability for their decisions and to halt dividend payments. Despite a number of investors speaking at the meeting and criticism from proxy voting advisers, the management resolutions were carried comfortably, reflecting the concentrated ownership of the Porsche and Piëch families.

A proxy contest at drugmaker Stada Arzneimittel may yet present activists with a path to influencing German companies, however. Investors defied management to elect a director selected by Active Ownership Capital (“AOC”), voted down Chairman Martin Abend and rejected the company’s remuneration plan. Other investors have openly called for the company to be sold, although AOC denied it would push for this.

The proxy contest at Stada Arzneimittel is a rare beast in a country that generally encourages activists to work more with management than directors to get things done. Even The Children’s Investment Fund Management, which has a fearsome reputation, is relying on its bully pulpit as a shareholder in Volkswagen to get things done, rather than initiating a formal contest. Activists have appointed supervisory board members in the past, however. Cevian Capital, a big player in the region, is currently involved at several construction sector companies.

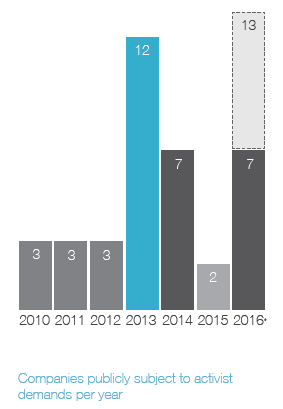

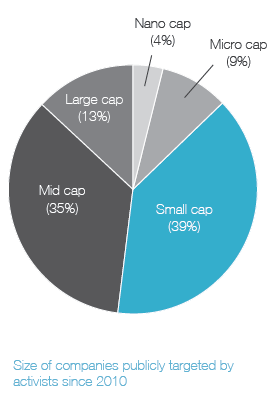

A wave of merger arbitrage by activists such as Kerrisdale Capital and Elliott Management as well the traditional activism of Cevian Capital made 2013 a banner year for activism in Germany. Cevian are showing the country more attention than ever, with 2016 on course to finish strongly.

* as of 30th June 2016. Projected full-year figures shown in dotted box.

Growing interest in activism in Germany has seen a wider range of market caps affected by activism since our last report. Both mid cap and large cap targets have increased in prominence, thanks to well-resourced activists showing interest in recent years.

New players rising

Shareholder activism in Germany continues to receive attention from the public, particularly with new domestic and short selling activists that understand how to utilise statutory legal instruments to implement their strategies entering the stage.

Elliott Management, a typical activist investor in special situations, continued to fiercely enforce its claim for an increase of the consideration for its 14.4% stake in Kabel Deutschland as part of the tender offer by Vodafone Group. In 2013, Elliott requested a special audit to review the offer of €84.53 per share. Since Vodafone vetoed a further special audit at the 2015 annual meeting, Elliott filed a court action requesting a further special audit alleging that €188 would have been fair; it seized upon its right pursuant to Sec. 145 German Stock Corporation Act (“AktG”). The court ruled in favour of Elliott, while the verdict of the further audit is outstanding.

Turning to “strategic” activists, with Active Ownership Capital (“AOC”) a new German player has entered the stage. In April 2016, AOC purchased a 5.1% position in Stada Arzneimittel and requested the replacement of initially five, later three, of the nine members of Stada’s supervisory board. Originally, Stada accepted these nominations but then changed its mind, eventually adjourning its annual meeting by nearly three months. Meanwhile AOC established a shareholders’ forum (Sec. 127a AktG) asking major shareholders to nominate candidates for election, eventually picking four to take into the proxy contest. Additionally, AOC called for the election of a new auditor; then it proposed the replacement of management board members even though the management board is appointed by the supervisory board whose members are independent from shareholders. AOC has been supported by Guy Wyser-Pratte and German Shareholder Value Management, drawing scrutiny by the German supervisory authority BaFin. It remains unclear whether AOC is seeking a longterm partnership or publicity to raise Stada’s market value, possibly with the goal of a sale; respective rumours of a partial or complete sale have evolved.

Besides the shareholders’ forum and direct communication with management, AOC essentially may use the following legal instruments: request that discharge of management not be granted on an individual basis (Sec. 120 para. 1 sent. 2 AktG), individual election of supervisory board members (Sec. 5.4.3 German Corporate Governance Code) and voting on its own director nominees prior to candidates proposed by management, thus enhancing their chances for election (Sec. 137 AktG).

The influence of activists is further proven by Cevian Capital’s investment in Bilfinger. For years Cevian has closely followed Bilfinger’s management and presumably “installed” Eckhard Cordes as chairman of the supervisory board, prompting various changes to the management board.

Aside from some other campaigns, a new kind of activists has emerged—those selling shares short and spreading news adversely affecting the share price. The lawfulness of this may be doubted. Examples include Muddy Waters (at Ströer) and Zatarra (Wirecard).

This illustrates the continuing increase in shareholder activism in Germany and that German law provides requisite instruments for it.

Italy

Shareholder representation on company boards is the rule and not the exception in Italy, with large investors dividing board seats amongst themselves and majority shareholders choosing managers. As of 2014, 83% of listed companies had a controlling shareholder, or a coalition of shareholders in control. However, the long-term trend is that the weight of the owners is slowly decreasing, and the presence of foreign institutional investors rising.

Moreover, the country’s prolonged economic crisis and new laws have weakened families and institutions that have controlled Italy’s largest companies for decades. Changes include the conversion of the largest co-operative banks into limited companies, a ban on director overboarding within competing entities in the financial sector, and limits on the grip of foundations on the country’s banks.

Railway signalling group Ansaldo STS has recently faced one of the most outspoken activist campaigns ever seen in the country, with Elliott Management and Amber Capital fighting for an increase in the price of a tender offer by Japan’s Hitachi—which recently acquired the Italian company’s controlling stake. Elliott also exploited Italy’s proxy access rules to elect three directors to the board of Ansaldo STS.

London-based Amber, which has an office in Milan, is also fighting a battle at dairy multinational Parmalat, where it has a board seat and accuses the controlling shareholder of improper related-party transactions.

In the 2016 proxy season, the Investment Managers’ Committee, an association assisting investment firms in nominating independent directors, submitted slates at 34 companies—up from 14 in 2013–and elected close to 60 board members, largely thanks to laws granting seats to minority shareholders.

Elliott Management has launched one of the most outspoken activist campaigns ever seen in Italy, electing three directors at Ansaldo STS and filing a lawsuit to gain complete control of the board. Amber Capital is engaging with several companies, and a battle with Parmalat’s largest shareholder that started in 2012 is still ongoing. In 2015, Vincent Bolloré’s Vivendi won three seats on the board of Telecom Italia.

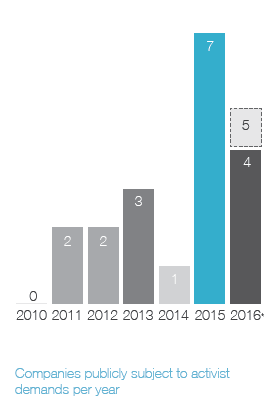

Activism in Italy has been rising steadily since the eurozone crisis, and 2016 is the busiest year on record as regulatory reform increases the scope for investors to apply pressure.

* as of 30th June 2016. Projected full-year figures shown in dotted box.

Activism in Italy is dominated by companies with a market capitalisation of less than 1.8 billion euros, although high-profile examples of large companies being targeted can be found.

Switzerland

Activism in Switzerland continues to play a role in several aspects of corporate life. Despite campaigns at the likes of Transocean, Xstrata and UBS, the country has previously been thought of as unfavourable to activism because, as in Germany, many companies have dual board structures. However, that failed to stop investors recently demanding changes to boards at Holcim, fashion retailer Charles Vögele and listed hedge fund Altin.

M&A activity including some of the largest Swiss companies, such as Syngenta and LafargeHolcim, has forced management teams to engage more meaningfully with shareholders, although investors have been less successful in wringing out meaningful concessions than in 2012, when a shareholder vote on golden parachutes for Xstrata executives forced the resignation of Chairman John Bond.

At Sika, a specialty chemicals company, Bill Gates’ family office Cascade Investment has opposed a takeover offer from Cie de Saint-Gobain, lobbying the takeover panel to force the bidder to tender for minority shareholders’ stakes. At the time of writing, Swiss courts were being asked to decide whether Sika could limit the majority voting rights of its founding family, which sold its 16% stake to the bidder.

A campaign at Altin highlights the lengths activists have to go to in Switzerland. In February, Alpine Select requisitioned a shareholder meeting to vote on the appointment of three new directors and a special dividend. When Alpine won just one seat on the board, its nominee resigned, and it went on to build a majority stake before negotiating an agreement whereby the company nominated three new directors, paid a hefty dividend and agreed to delist from the London Stock Exchange. Altin CEO Tony Morrongiello also announced his resignation in favour of Alpine’s Claudia Habermacher at the June annual meeting.

The restricted power of dual-class Swiss boards often limits investors to complaining about decisions from outside the boardroom—as with the appointment of Adecco’s new CEO—or legal action—as Bill Gates’ family office Cascade Investment is pursuing at Sika. Mergers have also catalysed activism, with Syngenta and Holcim targeted. As ever, Cevian Capital is present through its stake in ABB, while Swiss activist Telios may be one to watch in the future.

After an exceptionally busy 2015, this year has a lot to live up to. However, activists have started strongly, targeting more companies than in any year before 2015.

* as of 30th June 2016. Projected full-year figures shown in dotted box.

The make up of activist targets has changed only slightly in recent years. Many Swiss targets of activists being international by nature and often involved in crossborder mergers, the predominance of large cap targets is perhaps not surprising.