Voici le compte rendu hebdomadaire du forum de la Harvard Law School sur la gouvernance corporative au 25 octobre 2018.

Cette fois-ci, j’ai relevé les cinq principaux billets.

Bonne lecture !

Voici le compte rendu hebdomadaire du forum de la Harvard Law School sur la gouvernance corporative au 25 octobre 2018.

Cette fois-ci, j’ai relevé les cinq principaux billets.

Bonne lecture !

Dans un premier temps, j’ai tenté de répondre à cette question en renvoyant le lecteur à deux publications que j’ai faites sur le sujet. C’est du genre check-list !

Puis, dans un deuxième temps, je vous invite à consulter les documents suivants qui me semblent très pertinents pour répondre à la question. Il s’agit en quelque sorte d’une revue de la littérature sur le sujet.

J’espère que ces commentaires vous seront utiles, même si mon intervention est colorée par la situation canadienne et américaine !

Bonne lecture !

J’ai réalisé une entrevue avec le Journal des Affaires le 17 mars 2014. Une rédactrice au sein de l’Hebdo des AG, un média numérique qui se consacre au traitement des sujets touchant à la gouvernance des entreprises françaises, m’a contacté afin de connaître mon opinion sur quelles « prédictions » se sont effectivement avérées, et lesquelles restent encore à améliorer.

J’ai préparé quelques réflexions en référence aux douze tendances que j’avais identifiées le 17 mars 2014. J’ai donc revisité les tendances afin de vérifier comment la situation avait évolué en quatre ans. J’ai indiqué en rouge mon point de vue eu égard à ces tendances.

« Si la gouvernance des entreprises a fait beaucoup de chemin depuis quelques années, son évolution se poursuit. Afin d’imaginer la direction qu’elle prendra au cours des prochaines années, nous avons consulté l’expert en gouvernance Jacques Grisé, ex- directeur des programmes du Collège des administrateurs de sociétés, de l’Université Laval. Toujours affilié au Collège, M. Grisé publie depuis plusieurs années le blogue www.jacquesgrisegouvernance.com, un site incontournable pour rester à l’affût des bonnes pratiques et tendances en gouvernance. Voici les 12 tendances dont il faut suivre l’évolution, selon Jacques Grisé »

À ces 12 tendances, il faudrait en ajouter deux autres qui se sont révélées cruciales pour les conseils d’administration depuis quelques années :

(1) la mise en œuvre d’une politique de gestion des risques, l’identification des risques, l’évaluation des facteurs de risque eu égard à leur probabilité d’occurrence et d’impact sur l’organisation, le suivi effectué par le comité d’audit et par l’auditeur interne.

(2) le renforcement des ressources du conseil par l’ajout de compétences liées à la cybersécurité. La sécurité des données est l’un des plus grands risques des entreprises.

Récemment, je suis intervenu auprès du conseil d’administration d’une OBNL et j’ai animé une discussion tournant autour des thèmes suivants en affirmant certains principes de gouvernance que je pense être incontournables.

Vous serez certainement intéressé par les propositions suivantes :

(1) Le conseil d’administration est souverain — il est l’ultime organe décisionnel.

(2) Le rôle des administrateurs est d’assurer la saine gestion de l’organisation en fonction d’objectifs établis. L’administrateur a un rôle de fiduciaire, non seulement envers les membres qui les ont élus, mais aussi envers les parties prenantes de toute l’organisation. Son rôle comporte des devoirs et des responsabilités envers celle-ci.

(3) Les administrateurs ont un devoir de surveillance et de diligence ; ils doivent cependant s’assurer de ne pas s’immiscer dans la gestion de l’organisation (« nose in, fingers out »).

(4) Les administrateurs élus par l’assemblée générale ne sont pas porteurs des intérêts propres à leur groupe ; ce sont les intérêts supérieurs de l’organisation qui priment.

(5) Le président du conseil est le chef d’orchestre du groupe d’administrateurs ; il doit être en étroite relation avec le premier dirigeant et bien comprendre les coulisses du pouvoir.

(6) Les membres du conseil doivent entretenir des relations de collaboration et de respect entre eux ; ils doivent viser les consensus et exprimer leur solidarité, notamment par la confidentialité des échanges.

(7) Les administrateurs doivent être bien préparés pour les réunions du conseil et ils doivent poser les bonnes questions afin de bien comprendre les enjeux et de décider en toute indépendance d’esprit. Pour ce faire, ils peuvent tirer profit de l’avis d’experts indépendants.

(8) La composition du conseil devrait refléter la diversité de l’organisation. On doit privilégier l’expertise, la connaissance de l’industrie et la complémentarité.

(9) Le conseil d’administration doit accorder toute son attention aux orientations stratégiques de l’organisation et passer le plus clair de son temps dans un rôle de conseil stratégique.

(10) Chaque réunion devrait se conclure par un huis clos, systématiquement inscrit à l’ordre du jour de toutes les rencontres.

(11) Le président du CA doit procéder à l’évaluation du fonctionnement et de la dynamique du conseil.

(12) Les administrateurs doivent prévoir des activités de formation en gouvernance et en éthique.

Voici enfin une documentation utile pour bien appréhender les grandes tendances qui se dégagent dans le monde de la gouvernance aux É.U., au Canada et en France.

La considération de l’éthique et des valeurs d’intégrité sont des sujets de grande actualité dans toutes les sphères de la vie organisationnelle*. À ce propos, le Réseau d’éthique organisationnelle du Québec (RÉOQ) tient son colloque annuel les 25 et 26 octobre 2018 à l’hôtel Marriott Courtyard Montréal Centre-Ville et il propose plusieurs conférences qui traitent de l’éthique au quotidien. Je vous invite à consulter le programme du colloque et y participer.

Ne vous méprenez pas, la saine gouvernance des entreprises repose sur l’attention assidue accordée aux questions éthiques par le président du conseil, par le comité de gouvernance et d’éthique, ainsi que par tous les membres du conseil d’administration. Ceux-ci ont un devoir inéluctable de respect de la charte éthique approuvée par le CA.

Les défaillances en ce qui a trait à l’intégrité des personnes et les manquements de nature éthique sont souvent le résultat d’un conseil d’administration qui n’exerce pas un fort leadership éthique et qui n’affiche pas de valeurs transparentes à ce propos. Ainsi, il faut affirmer haut et fort que les comportements des employés sont largement tributaires de la culture de l’entreprise, des pratiques en cours, des contrôles internes… Et que les administrateurs sont les fiduciaires de ces valeurs qui font la réputation de l’entreprise !

Cette affirmation implique que tous les membres d’un conseil d’administration doivent faire preuve de comportements éthiques exemplaires : « Tone at the Top ». Les administrateurs doivent se donner les moyens d’évaluer cette valeur au sein de leur conseil, et au sein de l’organisation.

C’est la responsabilité du conseil de veiller à ce que de solides valeurs d’intégrité soient transmises à l’échelle de toute l’organisation, que la direction et les employés connaissent bien les codes de conduites et que l’on s’assure d’un suivi adéquat à cet égard.

Mais là où les CA achoppent trop souvent dans l’établissement d’une solide conduite éthique, c’est (1) dans la formulation de politiques probantes (2) dans la mise en place de l’instrumentalisation requise (3) dans le recrutement de personnes qui adhèrent aux objectifs énoncés et (4) dans l’évaluation et le suivi du climat organisationnel.

Les administrateurs doivent poser les bonnes questions sur la situation existante et prendre le recul nécessaire pour envisager les divers points de vue des parties prenantes dans le but d’assurer la transmission efficace du code de conduite de l’entreprise.

Les préconceptions et les préjugés sont coriaces, mais ils doivent être confrontés lors des échanges de vues au CA ou lors des huis clos. Les administrateurs doivent aborder les situations avec un esprit ouvert et indépendant.

Vous aurez compris que le président du conseil a un rôle clé à cet égard. C’est lui qui doit incarner le leadership en matière d’éthique et de culture organisationnelle. L’une de ses tâches est de s’assurer qu’il consacre le temps approprié aux questionnements éthiques. Pour ce faire, le président du CA doit poser des gestes concrets (1) en plaçant les considérations éthiques à l’ordre du jour (2) en s’assurant de la formation des administrateurs (3) en renforçant le rôle du comité de gouvernance et (4) en mettant le comportement éthique au cœur de ses préoccupations.

Le choix du premier dirigeant (PDG) est l’une des plus grandes responsabilités des conseils d’administration. Lors du processus de sélection, on doit s’assurer que le PDG incarne les valeurs éthiques qui correspondent aux attentes élevées des administrateurs ainsi qu’aux pratiques en vigueur. L’évaluation annuelle des dirigeants doit tenir compte de leur engagement éthique, et le résultat doit se refléter dans la rémunération variable des dirigeants.

Quels items peut-on utiliser pour évaluer la composante éthique de la gouvernance du conseil d’administration ? Voici un instrument qui peut aider à y voir plus clair. Ce cadre de référence novateur a été conçu par le Bureau de vérification interne de l’Université de Montréal.

| 1. Les politiques de votre organisation visant à favoriser l’éthique sont-elles bien connues et appliquées par ses employés, partenaires et bénévoles ? |

| 2. Le Conseil de votre organisation aborde-t-il régulièrement la question de l’éthique, notamment en recevant des rapports sur les plaintes, les dénonciations ? |

| 3. Le Conseil et l’équipe de direction de votre organisation participent-ils régulièrement à des activités de formation visant à parfaire leurs connaissances et leurs compétences en matière d’éthique ? |

| 4. S’assure-t-on que la direction générale est exemplaire et a développé une culture fondée sur des valeurs qui se déclinent dans l’ensemble de l’organisation ? |

| 5. S’assure-t-on que la direction prend au sérieux les manquements à l’éthique et les gère promptement et de façon cohérente ? |

| 6. S’assure-t-on que la direction a élaboré un code de conduite efficace auquel elle adhère, et veille à ce que tous les membres du personnel en comprennent la teneur, la pertinence et l’importance ? |

| 7. S’assure-t-on de l’existence de canaux de communication efficaces (ligne d’alerte téléphonique dédiée, assistance téléphonique, etc.) pour permettre aux membres du personnel et partenaires de signaler les problèmes ? |

| 8. Le Conseil reconnaît-il l’impact sur la réputation de l’organisation du comportement de ses principaux fournisseurs et autres partenaires ? |

| 9. Est-ce que le président du Conseil donne le ton au même titre que le DG au niveau des opérations sur la culture organisationnelle au nom de ses croyances, son attitude et ses valeurs ? |

|

10. Est-ce que l’organisation a la capacité d’intégrer des changements à même ses processus, outils ou comportements dans un délai raisonnable ? |

*Autres lectures pertinentes :

Plusieurs personnes très qualifiées me demandent comment procéder pour décrocher un poste d’administrateur de sociétés… rapidement.

Dans une période où les conseils d’administration ont des tailles de plus en plus restreintes ainsi que des exigences de plus en plus élevées, comment faire pour obtenir un poste, surtout si l’on a peu ou pas d’expérience comme CEO d’une entreprise ?

Je leur réponds qu’ils doivent :

(1) viser un secteur d’activité dans lequel ils ont une solide expertise

(2) bien comprendre ce qui les démarque (en revisitant leur CV)

(3) se demander comment leurs avantages comparatifs peuvent ajouter de la valeur à l’organisation

(4) explorer comment ils peuvent faire appel à leurs réseaux de contacts

(5) s’assurer de bien comprendre l’industrie et le modèle d’affaires de l’entreprise

(6) bien faire connaître leurs champs d’intérêt et leurs compétences en gouvernance, notamment en communiquant avec le président du comité de gouvernance de l’entreprise convoitée, et

(7) surtout… d’être patients !

Si vous n’avez pas suivi une formation en gouvernance, je vous encourage fortement à consulter les programmes du Collège des administrateurs de sociétés (CAS).

L’article qui suit présente une démarche de recherche d’un mandat d’administrateur en six étapes. L’article a été rédigé par Alexandra Reed Lajoux, directrice de la veille en gouvernance à la National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD).

Vous trouverez, ci-dessous, une brève introduction de l’article paru sur le blogue de Executive Career Insider, ainsi qu’une énumération des 6 éléments à considérer.

Je vous conseille de lire ce court article en vous rappelant qu’il est surtout destiné à un auditoire américain. Vous serez étonné de constater les similitudes avec la situation canadienne.

Of all the career paths winding through the business world, few can match the prestige and fascination of corporate board service. The honor of being selected to guide the future of an enterprise, combined with the intellectual challenge of helping that enterprise succeed despite the odds, make directorship a strong magnet for ambition and a worthy goal for accomplishment.

Furthermore, the pay can be decent, judging from the NACD and Pearl Meyer & Partners director compensation studies. While directors do risk getting underpaid for the accordion-like hours they can be called upon to devote (typical pay is a flat retainer plus stock, but hours are as needed with no upper limit), it’s typically equivalent to CEO pay, if considered hour for hour. For example, a director can expect to work a good 250 hours for the CEO’s 2,500 and to receive nearly 10 percent of the CEO’s pay. In a public company that can provide marketable equity (typically half of pay), the sums can be significant—low six figures for the largest global companies.

Granted, directorship cannot be a first career. As explained in my previous post, boards offer only part time engagements and they typically seek candidates with track records. Yet directorship can be a fulfilling mid-career sideline, and a culminating vocation later in life—for those who retire from day to day work, but still have much to offer.

So, at any age or stage, how can you get on a board? Here are 6 steps, representing common wisdom and some of my own insights based on what I have heard from directors who have searched for – or who are seeking – that first board seat.

1. Recast your resume – and retune your mindset – for board service. Before you begin your journey, remember that the most important readers of your resume will be board members in search of a colleague. As such, although they will be duly impressed by your skills and accomplishments as an executive, as they read your resume or talk to you in an interview they will be looking and listening for clues that you will be an effective director. Clearly, any board positions you have had – including nonprofit board service, work on special committees or task forces and the like should be prominent on your resume and in your mind.

2. Integrate the right keywords. Language can be tuned accordingly to “directorspeak.” Any language that suggests you singlehandedly brought about results should be avoided. Instead, use language about “working with peers,” “dialogue,” and “stewardship” or “fiduciary group decisions, » « building consensus, » and so forth. While terms such as “risk oversight,” “assurance,” “systems of reporting and compliance,” and the like should not be overdone (boards are not politbureaus) they can add an aura of governance to an otherwise ordinary resume. This is not to suggest that you have two resumes – one for executive work and one for boards. Your use of boardspeak can enhance an existing executive resume. So consider updating the resume you have on Bluesteps and uploading that same resume to NACD’s Directors Registry.

3. Suit up and show up—or as my colleague Rochelle Campbell, NACD senior member engagement manager, often says, “network, network, network.” In a letter to military leaders seeking to make a transition From Battlefield to Boardroom (BtoB)through a training program NACD offers for military flag officers, Rochelle elaborates: “Make sure you attend your local chapter events—and while you are there don’t just shake hands, get to know people, talk to the speakers, and create opportunities for people to learn about you and your capabilities, not just your biography.” Rochelle, who has helped military leaders convey the value of their military leadership experience to boards, adds: “Ensure when you are networking, that you are doing so with a purpose. Include in your conversations that you are ready, qualified, and looking for a board seat.” Rochelle also points out the value of joining one’s local Chamber of Commerce and other business groups in relevant industries.

4. Cast a wide net. It is unrealistic for most candidates to aim for their first service to be on a major public company board. Your first board seat will likely be an unpaid position on a nonprofit board, or an equity-only spot on a start-up private board, or a small-cap company in the U.S. or perhaps oversees. Consider joining a director association outside the U.S. Through the Global Network of Director Institutes‘ website you can familiarize yourself with the world’s leading director associations. Some of them (for example, the Institute of Directors in New Zealand) send out regular announcements of open board seats, soliciting applications. BlueSteps members also have access to board opportunities, including one currently listed for in England seeking a non-executive director.

5. Join NACD. As long as you serve as a director on a board (including even a local nonprofit) you can join NACD as an individual where you will be assigned your own personal concierge and receive an arrange of benefits far too numerous to list here. (Please visit NACDonline.org to see them.) If you seek additional board seats beyond the one you have, you will be particularly interested in our Directors Registry, where NACD members can upload their resumes and fill out a profile so seeking boards can find them. Another aspect will be your ability to attend local NACD chapter events, many of which are closed to nonmembers. You can also join NACD as a Boardroom Executive Affiliate no matter what your current professional status.

6. Pace yourself. If you are seeking a public company board seat, bear in mind that a typical search time will be more than two years, according to a relevant survey from executive search firm Heidrick & Struggles and the affinity group WomenCorporateDirectors. That’s how long on average that both female and male directors responding to the survey said it took for them to get on a board once they started an active campaign. (An earlier H&S/WCD survey had indicated that it took more time for women than for men, but that discrepancy seems to have evened out now – good news considering studies by Credit Suisse and others showing a connection between gender diversity and corporate performance.) Remember that the two years is how long it took successful candidates to land a seat (people looking back from a boardroom seat on how long it took to get them there). If you average in the years spent by those who never get a board seat and gave up, the time would be longer. This can happen.

An Uphill Battle

Jim Kristie, longtime editor of Directors & Boards, once shared a poignant letter from one of his readers, whose all too valid complaint he called “protypical”:

When I turned 50, I felt like I had enough experience to add value to a public board of directors. I had served on private boards. I joined the National Association of Corporate Directors, and began soliciting smaller public companies to serve on their boards. I even solicited pink sheet companies. I solicited private equity firms to serve on the boards of portfolio companies. I signed up with headhunters, and Nasdaq Board Recruiting. In the last several years, I have sent my CV to hundreds of people, and made hundreds of telephone calls. I have been in the running, but so far no board positions.

Jim responded that the individual had done “all the right things” (thanks for the endorsement!) and steered him to additional relevant resources.

Similarly, a highly respected military flag officer, an Army general who spent two solid years looking for a board seat with help from NACD, called his search an “uphill battle.” While four-star generals tend to attract invitations for board service, flag officers and others do not always get the attention they merit from recruiters and nominating committees. In correspondence to our CEO, he praised the BtoB program, but had some words of realism:

My experience over the past two years has convinced me that until sitting board room members see the value and diversity of thought that a B2B member brings, we will never see an appreciable rise in board room membership beyond the defense industry and even then, they only really value flag membership for the access they bring. The ‘requirements’ listed for new board members coming from industry will rarely match with a B2B resume and until such time that boards understand the value that comes with having a B2B member as part of their leadership team, they probably never will.

We’ve heard similar words from other kinds of leaders—from human resources directors to chief internal auditors, to university presidents. With so few board seats opening up every year, and with a strong leaning toward for-profit CEOs, it’s a real challenge to get through the boardroom door.

One of NACD’s long-term goals is to educate existing boards on the importance of welcoming these important forms of leadership, dispelling the notion that only a for-profit CEO can serve. For example, I happen to believe that a tested military leader can offer boards as much as or more than a civilian leader in the current high-risk environment. But no matter what your theatre of action, you must prepare for a long campaign. It’s worth the battle!

Une autre semaine prolifique sur le site de HLS !

Voici le compte rendu hebdomadaire du forum de la Harvard Law School sur la gouvernance corporative au 18 octobre 2018.

Cette semaine, j’ai choisi les dix billets suivants.

Bonne lecture !

Voici le compte rendu hebdomadaire du forum de la Harvard Law School sur la gouvernance corporative au 11 octobre 2018.

Comme à l’habitude, j’ai relevé les dix principaux billets.

Bonne lecture !

Semaine prolifique sur le site de HLS !

Voici le compte rendu hebdomadaire du forum de la Harvard Law School sur la gouvernance corporative au 4 octobre 2018.

Cette semaine, j’ai relevé les quinze principaux billets.

Bonne lecture !

Voici le compte rendu hebdomadaire du forum de la Harvard Law School sur la gouvernance corporative au 27 septembre 2018.

Comme à l’habitude, j’ai relevé les dix principaux billets.

Bonne lecture !

Ce matin un article de Alissa Amico*, paru sur le forum de Harvard Law School, a attiré mon attention parce que c’est sur un sujet qui fait couler beaucoup d’encre dans le domaine la gouvernance des entreprises publiques (cotées en bourse).

En effet, quels sont les moyens appropriés de diffusion et de divulgation des informations à l’ère des médias sociaux ? L’auteure fait le tour de la question en rappelant qu’il existe encore beaucoup d’ambiguïté dans l’acceptation des nouveaux outils de communication.

On le sait, la SEC a réagi promptement aux annonces de Elon Musk, PDG et Chairman de Telsa, faites par le biais de Twitter qui ont été jugées trompeuses et qui ne respectaient pas le principe d’une diffusion de l’information à la portée de tous les actionnaires.

L’auteure rappelle que l’Autorité des Marchés Financiers français a pris une position ferme à ce propos en exigeant que les entreprises divulguent leurs réseaux sociaux privilégiés de communication sur leur site Internet.

La conclusion de l’article est révélatrice de grands changements à l’égard de la diffusion d’information stratégique.

The ultimate twist of irony is of course that the SEC, investigating Tesla and its CEO, is part of the same government whose President’s tweeting activity has been far from uncontroversial. Both Mr. Musk’s and Mr. Trump’s use of Twitter highlight that—whether we like it or not—social media may soon be the most consulted sort of media. Its impact, in both corporate or political circles, needs hence to be considered by policymakers seriously. It is clear that every boat—whether corporate or political—needs a captain responsible for setting the course and communicating it to the lighthouse to avoid collisions and confusion at sea. Yet, captains are not pirates, and in the era of social media, regulators need to devise new rules of the game to avoid investor collusion and collision.

Qu’en pensez-vous ?

Bonne lecture !

There was something Trumpian in Elon Musk’s tweet about taking Tesla private. “Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured”, he boldly and succinctly announced on August 7, claiming that the necessary capital has been confirmed from the Public Investment Fund (PIF), the Saudi sovereign fund that is seeking to become the region’s largest according to the ambitions of its government, including through the much-debated public offering of Saudi Aramco.

Like in a Mexican soap opera, news about the PIF raising fresh capital through the transfer of its 70% stake in SABIC, the Saudi $100 billion petrochemicals giant and the largest listed company in the Kingdom to Saudi Aramco, as well its talks with Tesla’s rival Lucid followed shortly, immediately highlighting the perils of instant communication. As it turns out, tweeting 280-character messages is straightforward, explaining them takes a little more character and significantly more characters.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has reacted promptly, issuing a subpoena to Tesla to probe into the accuracy of its communication to investors. Elon Musk is unfortunately not the first CEO to pay for taking to Twitter. Nestle’s attempt at humor on Twitter, which likened a massacre of Mexican students to its candy bar, resulted in calls for boycott, ultimately forcing the company to erase the message and apologize. Even the CEO of Twitter itself, Jack Dorsey, has had to apologize for one of his personal tweets, which unlike Tesla and Nestle cases, had nothing to do with his company.

Indeed, the emergence of new communication channels has occurred at a faster pace than regulation on how these should be employed by companies has emerged, whilst over-excited executives have taken to social media in attempt to build hype around their companies. In the world where the number of Instagram, Twitter and Facebook followers counts more than the number of public investors, social media has the potential of becoming the main channel for communication in the corporate world.

Although this phenomenon has gone largely unnoticed, its implications need to be considered in a wider context that is beyond this immediate Bermuda Triangle involving Mr. Musk, the PIF and Tesla. In fact, this episode raises two important and distinct questions: first, who should be able to speak on behalf of public shareholding companies in order to ensure the accuracy of communication, and second, how should this communication be made such that it reaches its ultimate target, the investor community.

In developed markets such as the United States, where Tesla is incorporated, disclosure by public companies is subject to a myriad of regulations including Rule 10b-5—first issued 70 years ago—which prohibits the release or omission of material information, resulting in fraud or deceit. It is also subject to a more recent Fair Disclosure Regulation which essentially forbids companies from releasing non-public material information to third parties, effectively stamping out the practice of selective disclosure by companies to specific investors.

These regulations provide the colorful context behind the SEC’s investigation into Mr. Musk’s unfortunate tweet, allowing the regulator to question whether he had misled investors: that is, whether funding for taking Tesla private has indeed been “secured”. Another issue—and one not raised in the media—is whether Twitter can effectively be considered as an appropriate means of communication to the investor community. In the United States, where 70% of public share ownership today is in the hands of institutional investors, this is a moot point.

Indeed, the SEC has officially allowed listed companies to use social media in 2013, prompted by an investigation into a Facebook post by the Netflix CEO Reed Hastings about the company passing a billion hours watched for the first time. The SEC did not penalize him and decided that henceforth social media could be used for communicating corporate announcements as long as investors are warned that this would be the case.

In the context of emerging markets however, this position would be potentially quite dangerous. In Saudi Arabia for example, home to the PIF—Tesla’s alleged buyer—trading in the stock market is 90% retail, whereas its underlying ownership is largely institutional. Communicating company news via social media presupposes that all investors have equal access to it, which may not necessarily be the case in retail marketplaces. Regulators in emerging markets, where guidelines on the use of social media for corporate announcements are generally lacking, would do well to address this before executives take to Twitter and Facebook.

They would need to keep in mind however, that habits of emerging market investors may not have shifted fast enough to be comfortable in the world of Twitter. In Egypt for example, the officially recognised channel for publishing financial results remains the country’s newspapers. Expecting investors to run from conventional—not to say outdated—means of communication, to judiciously tracking social media announcements appears overly ambitious.

Using social media as a means of communicating material corporate news raises another non-semantic point which is equally important to address in both emerging and developed markets. It is not only tweets of CEOs like Elon Musk that have the potential to affect share prices and investor perceptions. If CFOs, CROs, CIOs, COOs and other C-suite members take to Twitter, Facebook, Instagram or other platforms to offer their interpretation of company developments, the potential impact on investors could be quite disheartening.

Just like the CEO’s or the CFO’s ability to write a cheque is circumscribed by internal controls and board oversight of material transactions related to mergers and acquisitions for instance, their ability to speak on behalf of their companies should be addressed by policies including specific approval processes. This would effectively limit the possibility of senior executives or board members using their iPhone as a Megaphone, instead requiring rigorous processes to be introduced such that social media announcements are coherent with other disclosure channels and indeed with corporate strategy.

From a governance perspective, further thought should be given to centralizing the communication function within companies in the hands of the Head of Investor Relations or equivalent. Indeed, given the value of information in our era of fast-paced communication powered by social media and fast-paced stock exchanges powered by algorithmic and high-frequency trading, the role of a Chief Communication Officer may be justified in large publicly listed companies, just as the role of a Chief Risk Officer reporting to the board has been introduced in many large organisations following the financial crisis.

While forcing companies in a straightjacket of yet more corporate governance rules on how they should handle their corporate communications may be unwise, some thought about legal distinctions and limits between what is considered personal and corporate announcements appears warranted. Investors may need to be told that unless corporate announcements come from official company channels—which personal Twitter accounts are not—their interpretation of tweets by excited executives are to be made at their own peril, not subject to usual investor protections.

Likewise, publicly-traded companies need to inform the investor community of what constitutes their official communication channels and ensure that financial and non-financial information announced through these is pre-approved, synchronized and not in conflict with existing regulations. Some regulators such as the French securities regulator, Authorité des Marches Financiers, has done so almost 5 years ago, recommending that companies specify their social media accounts on their website as well as establish a charter addressing how executives and staff are to use their personal social media accounts.

The ultimate twist of irony is of course that the SEC, investigating Tesla and its CEO, is part of the same government whose President’s tweeting activity has been far from uncontroversial. Both Mr. Musk’s and Mr. Trump’s use of Twitter highlight that—whether we like it or not—social media may soon be the most consulted sort of media. Its impact, in both corporate or political circles, needs hence to be considered by policymakers seriously. It is clear that every boat—whether corporate or political—needs a captain responsible for setting the course and communicating it to the lighthouse to avoid collisions and confusion at sea. Yet, captains are not pirates, and in the era of social media, regulators need to devise new rules of the game to avoid investor collusion and collision.

*Alissa Amico is the Managing Director of GOVERN. This post is based on a GOVERN memorandum by Ms. Amico.

La considération de l’éthique et des valeurs d’intégrité sont des sujets de grande actualité dans toutes les sphères de la vie organisationnelle*. À ce propos, le Réseau d’éthique organisationnelle du Québec (RÉOQ) tient son colloque annuel les 25 et 26 octobre 2018 à l’hôtel Marriott Courtyard Montréal Centre-Ville et il propose plusieurs conférences qui traitent de l’éthique au quotidien. Je vous invite à consulter le programme du colloque et y participer.

Ne vous méprenez pas, la saine gouvernance des entreprises repose sur l’attention assidue accordée aux questions éthiques par le président du conseil, par le comité de gouvernance et d’éthique, ainsi que par tous les membres du conseil d’administration. Ceux-ci ont un devoir inéluctable de respect de la charte éthique approuvée par le CA.

Les défaillances en ce qui a trait à l’intégrité des personnes et les manquements de nature éthique sont souvent le résultat d’un conseil d’administration qui n’exerce pas un fort leadership éthique et qui n’affiche pas de valeurs transparentes à ce propos. Ainsi, il faut affirmer haut et fort que les comportements des employés sont largement tributaires de la culture de l’entreprise, des pratiques en cours, des contrôles internes… Et que les administrateurs sont les fiduciaires de ces valeurs qui font la réputation de l’entreprise !

Cette affirmation implique que tous les membres d’un conseil d’administration doivent faire preuve de comportements éthiques exemplaires : « Tone at the Top ». Les administrateurs doivent se donner les moyens d’évaluer cette valeur au sein de leur conseil, et au sein de l’organisation.

C’est la responsabilité du conseil de veiller à ce que de solides valeurs d’intégrité soient transmises à l’échelle de toute l’organisation, que la direction et les employés connaissent bien les codes de conduites et que l’on s’assure d’un suivi adéquat à cet égard.

Mais là où les CA achoppent trop souvent dans l’établissement d’une solide conduite éthique, c’est (1) dans la formulation de politiques probantes (2) dans la mise en place de l’instrumentalisation requise (3) dans le recrutement de personnes qui adhèrent aux objectifs énoncés et (4) dans l’évaluation et le suivi du climat organisationnel.

Les administrateurs doivent poser les bonnes questions sur la situation existante et prendre le recul nécessaire pour envisager les divers points de vue des parties prenantes dans le but d’assurer la transmission efficace du code de conduite de l’entreprise.

Les préconceptions et les préjugés sont coriaces, mais ils doivent être confrontés lors des échanges de vues au CA ou lors des huis clos. Les administrateurs doivent aborder les situations avec un esprit ouvert et indépendant.

Vous aurez compris que le président du conseil a un rôle clé à cet égard. C’est lui qui doit incarner le leadership en matière d’éthique et de culture organisationnelle. L’une de ses tâches est de s’assurer qu’il consacre le temps approprié aux questionnements éthiques. Pour ce faire, le président du CA doit poser des gestes concrets (1) en plaçant les considérations éthiques à l’ordre du jour (2) en s’assurant de la formation des administrateurs (3) en renforçant le rôle du comité de gouvernance et (4) en mettant le comportement éthique au cœur de ses préoccupations.

Le choix du premier dirigeant (PDG) est l’une des plus grandes responsabilités des conseils d’administration. Lors du processus de sélection, on doit s’assurer que le PDG incarne les valeurs éthiques qui correspondent aux attentes élevées des administrateurs ainsi qu’aux pratiques en vigueur. L’évaluation annuelle des dirigeants doit tenir compte de leur engagement éthique, et le résultat doit se refléter dans la rémunération variable des dirigeants.

Quels items peut-on utiliser pour évaluer la composante éthique de la gouvernance du conseil d’administration ? Voici un instrument qui peut aider à y voir plus clair. Ce cadre de référence novateur a été conçu par le Bureau de vérification interne de l’Université de Montréal.

| 1. Les politiques de votre organisation visant à favoriser l’éthique sont-elles bien connues et appliquées par ses employés, partenaires et bénévoles ? |

| 2. Le Conseil de votre organisation aborde-t-il régulièrement la question de l’éthique, notamment en recevant des rapports sur les plaintes, les dénonciations ? |

| 3. Le Conseil et l’équipe de direction de votre organisation participent-ils régulièrement à des activités de formation visant à parfaire leurs connaissances et leurs compétences en matière d’éthique ? |

| 4. S’assure-t-on que la direction générale est exemplaire et a développé une culture fondée sur des valeurs qui se déclinent dans l’ensemble de l’organisation ? |

| 5. S’assure-t-on que la direction prend au sérieux les manquements à l’éthique et les gère promptement et de façon cohérente ? |

| 6. S’assure-t-on que la direction a élaboré un code de conduite efficace auquel elle adhère, et veille à ce que tous les membres du personnel en comprennent la teneur, la pertinence et l’importance ? |

| 7. S’assure-t-on de l’existence de canaux de communication efficaces (ligne d’alerte téléphonique dédiée, assistance téléphonique, etc.) pour permettre aux membres du personnel et partenaires de signaler les problèmes ? |

| 8. Le Conseil reconnaît-il l’impact sur la réputation de l’organisation du comportement de ses principaux fournisseurs et autres partenaires ? |

| 9. Est-ce que le président du Conseil donne le ton au même titre que le DG au niveau des opérations sur la culture organisationnelle au nom de ses croyances, son attitude et ses valeurs ? |

|

10. Est-ce que l’organisation a la capacité d’intégrer des changements à même ses processus, outils ou comportements dans un délai raisonnable ? |

*Autres lectures pertinentes :

Voici le compte rendu hebdomadaire du forum de la Harvard Law School sur la gouvernance corporative au 20 septembre 2018.

Comme à l’habitude, j’ai relevé les dix principaux billets.

Bonne lecture !

Les investisseurs qui croient dans le génie de cet entrepreneur sont en droit de s’attendre à ce que le fondateur mette en place des systèmes de gouvernance qui respectent les parties prenantes, dont les investisseurs.

Ces comportements de dominance sont tributaires du conseil d’administration où le fondateur joue le rôle de « Chairman, Product architect and CEO », comme s’il était le propriétaire de tout le capital de l’entreprise.

On peut comprendre la confiance que les investisseurs mettent en Musk, mais jusqu’à quel point doivent-ils ignorer certaines règles fondamentales de gouvernance d’entreprise ?

On connaît plusieurs entreprises qui sont dominées complètement par leur fondateur-entrepreneur. Ces comportements « dysfonctionnels » ne sont pas toujours signe de mauvaise performance à court terme. Mais, à long terme, sans de solides principes de gouvernance, ces entreprises rencontrent généralement des problèmes de croissance.

Selon l’auteur Kevin Reed,

Elon Musk, Tesla’s “chairman, product architect and CEO”, has recently the displayed classic traits of a dominant, idiosyncratic and controversial boss which, according to one commentator, is a sure sign of weak governance.

Voici un aperçu de l’argumentaire présenté dans l’article.

Bonne lecture !

There has been a long history of dominant, sometimes idiosyncratic and often irascible CEOs.

They will court controversy—which can be directly related to the business’s strategy and operations, or linked to “non-corporate” behaviour or actions.

Names such as Mike Ashley, Lord Sugar and even “shareholder-return-friendly” Sir Martin Sorrell have shown how outspoken and autocratic leaders will find their approach strongly questioned or criticised.Names such as Mike Ashley, Lord Sugar and even “shareholder-return-friendly” Sir Martin Sorrell have shown how outspoken and autocratic leaders will find their approach strongly questioned or criticised—usually during tough times, despite previous spells of success.

However, recent proclamations on social and traditional media by Tesla’s Elon Musk could well be viewed as beyond the pale.

Whether offering a mini-submarine to rescue children stuck in a Thai cave, to making lewd accusations about another rescuer, through to proclaiming on Twitter that he is considering taking Tesla private, it puts into question whether such behaviour damages shareholder value.

“The tale of Elon Musk is a sadly familiar story of a founder who through vision, drive, ambition and talent grows a company to fantastic levels, but who then seems unable to accept challenge and healthy criticism and feels unable to operate in an appropriate governance environment,” explains Iain Wright, director of corporate and regional engagement at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW).

Crashing companies onto rocks

Wright believes that we have seen “time and time again” dominant founders and chiefs “crash those companies onto the rocks” through “weak corporate governance”.

An important part of reining in such dominance is through the board and, namely, the chairman. They need to be able to support someone with the vision and entrepreneurial spirit of someone like Musk, but also challenge them on behalf of the company and its stakeholders to “curb some of his erratic behaviour”.

“The board is subservient to the founder and chief executive rather than the other way round.”He adds: “Good corporate governance would put in place a board who would challenge this, led by a chair who has the authority, experience and gravitas to stand up to Musk and tell him to have a holiday and get some sleep.”

And so, what of Tesla’s chairman? Well, that’s Elon Musk, whose full title is “chairman, product architect and CEO”. Attempts to separate the roles and appoint a chairman have been rebuffed by the board in the past, stating that it has a lead independent director in place.

This director is Antonio Gracias, a private equity investor who has reportedly shared many years associated with Musk.

“The board is subservient to the founder and chief executive rather than the other way round,” suggests Wright. “Musk is both chairman and CEO of Tesla, a situation relatively common in the States but quite properly frowned upon as inappropriate corporate governance in the UK.”

Separating the role is for the “long-term benefit of the company”, adds Wright. “This proposal should come back on the table soon.”

Mettez-vous à la place de Robert Dutton. Se faire mettre à la porte de «son» entreprise après 35 années de loyaux services, dont 20 à titre de président et chef de la direction, c’est à la fois blessant et révoltant.

La blessure est d’autant plus grande lorsque vous découvrez que votre départ avait en fait pour finalité de permettre aux gros actionnaires, dont la Caisse de dépôt et placement, de faire la piastre en vendant l’entreprise à une multinationale américaine.

Farouche défenseur d’un Québec inc. qui protège ses sièges sociaux, l’ancien grand patron de RONA, Robert Dutton, ne voulait rien savoir des offres d’acquisition de Lowe’s.

Inconcevable

Pour lui, il était inconcevable de voir RONA devenir une filiale d’une multinationale étrangère.

Pour les gros fonds institutionnels qui détiennent des blocs d’actions de votre entreprise, il était évident qu’un PDG comme Dutton représentait un obstacle majeur.

C’est le genre de gars capable de déplacer des montagnes pour protéger l’entreprise contre les prédateurs étrangers.

Les dessous de la vente de RONA : l’ex-PDG ne voulait rien savoir des offres de Lowe’s

Voici le compte rendu hebdomadaire du forum de la Harvard Law School sur la gouvernance corporative au 6 septembre 2018.

Comme à l’habitude, j’ai relevé les dix principaux billets.

Bonne lecture !

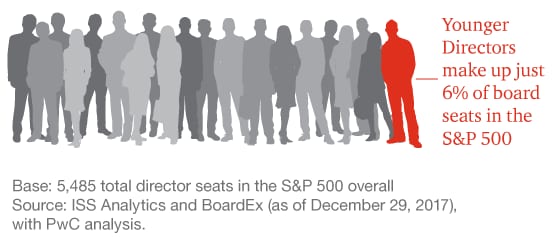

Lorsque l’on parle de diversité au sein des conseils d’administration, on se réfère, la plupart du temps, à la composition du CA sur la base des genres et des origines ethniques.

L’âge des nouveaux administrateurs est une variable de diversité trop souvent négligée de la composition des CA. Dans cette enquête complète de PwC, les auteurs mettent l’accent sur les caractéristiques des administrateurs qui ont moins de 50 ans et qui servent sur les CA du S&P 500.

Cette étude de PwC est basée sur des données statistiques objectives provenant de diverses sources de divulgation des grandes entreprises américaines.

En consultant la table des matières du rapport, on constate que l’étude vise à répondre aux questions suivantes :

(1) Quelle est la population des jeunes administrateurs sur les CA du S&P 500 ?

Ils sont peu nombreux, et ils ne sont pas trop jeunes !

Ils ont été nommés récemment

Les femmes font une entrée remarquable, mais pas dans tous les groupes…

(2) Qu’y a-t-il de particulier à propos des « jeunes administrateurs » ?

96 % occupent des emplois comme hauts dirigeants, 31 % des jeunes administrateurs indépendants sont CEO provenant d’autres entreprises,

Plus de la moitié proviennent des secteurs financiers et des technologies de l’information

Ils sont capables de concilier les exigences de leurs emplois avec celles de leurs rôles d’administrateurs

Ils sont recherchés pour leurs connaissances en finance/investissement ou pour leurs expertises en technologie

90 % des jeunes administrateurs siègent à un comité du CA et 50 % siègent à deux comités

La plupart évitent de siéger à d’autres conseils d’administration

(3) Quelles entreprises sont les plus susceptibles de nommer de jeunes administrateurs ?

Les jeunes CEO représentent une plus grande probabilité d’agir comme administrateurs indépendants

Plus de 50 % des jeunes administrateurs indépendants proviennent des secteurs des technologies de l’information, et des produits aux consommateurs

Les secteurs les moins pourvus de jeunes administrateurs sont les suivants : télécommunications, utilités, finances et immobiliers

Les plus jeunes administrateurs expérimentent des relations mutuellement bénéfiques.

La conclusion de l’étude c’est qu’il est fondamental de repenser la composition des CA en fonction de l’âge. Les conseils prodigués relatifs à l’âge sont les suivants :

Have you analyzed the age diversity on your board, or the average age of your directors?

Does your board have an updated succession plan? Does age diversity play into considerations for new board members?

Are there key areas where your board lacks current expertise—such as technology or consumer habits? Could a new—and possibly younger—board member bring this knowledge?

Does your board have post-Boomers represented?

Does your board have a range of diversity of thought—not just one or two people in the room who you look to continually for the “diversity angle”?

Could younger directors bring some needed change to the boardroom?

Notons que cette étude a été faite auprès des grandes entreprises américaines. Dans l’ensemble de la population des entreprises québécoises, la situation est assez différente, car il y a beaucoup plus de jeunes sur les conseils d’administration.

Mais, à mon avis, il y a encore de nombreux efforts à faire afin de rajeunir et renouveler nos CA.

Bonne lecture !

There are 315 Younger Directors in the S&P 500. Together, they hold 348 board seats of companies in the index. Of these 348 Younger Director seats, 260 are filled by independent Younger Directors.

Fewer than half of S&P 500 companies have a Younger Director. Only 43% of the S&P 500 (217 companies) have at least one Younger Director on the board. At 50 of those companies, one of the Younger Directors is the company’s CEO.

S&P 500 companies with younger CEOs are much more likely to have independent Younger Directors on the board. Sixty percent (60%) of the 527 companies with a CEO aged 50 or under have at least one independent Younger

Director on the board—as compared to just 42% of companies that have a CEO over the age of 50.Almost one-third of Younger Directors are women. Women comprise a much larger percentage (31%) of Younger Directors than in the S&P 500 overall (22%). This is in spite of the fact that over 90% of Younger Directors nominated under

shareholder agreements—such as those with an activist, private equity investor or family shareholder—are men.Information technology and consumer products companies are more likely to have Younger Directors. The three companies in the telecommunications sector have no Younger Directors.

Close to half of the independent Younger Directors have finance/investing backgrounds. Just under one-third are cited for their technology expertise, executive experience or industry knowledge.

Younger Directors fit in board service while pursuing their careers. According to their companies’ SEC filings, 96% of Younger Directors cite active jobs or positions in addition to their board service.

Younger Directors serve on fewer boards. The average independent S&P 500 director sits on 2.1 public company boards. In contrast, independent Younger Directors sit on an average of 1.7 boards. More than half serve on only one public board.

More than half of the independent Younger Directors have held their board seat for two years or less. Only 18% have been on the board for more than five yearsé

Voici le compte rendu hebdomadaire du forum de la Harvard Law School sur la gouvernance corporative au 30 août 2018.

Comme à l’habitude, j’ai relevé les dix principaux billets.

Bonne lecture !

Aujourd’hui, je vous propose la lecture d’un article sur l’évolution de la gouvernance chinoise.

Les auteurs, Jamie Allen*et Li Rui, de la Asian Corporate Governance Association (ACGA), ont produit un excellent rapport sur les changements que vivent les entreprises chinoises eu égard à la gouvernance.

L’étude se base sur une enquête auprès d’entreprises chinoises et auprès d’investisseurs étrangers. Également, les auteurs présentent une mine d’information sur la situation de la gouvernance.J’ai reproduit, ci-après, un résumé de l’enquête.

Bonne lecture !

With its securities market continuing to internationalise and grow in complexity, China appears at a turning point in its application of CG and ESG principles.

The time is right to strengthen communication and understanding between domestic and foreign market participants.

Introduction: Bridging the gap

The story of modern corporate governance in China is closely connected to the rapid evolution of its capital markets following the opening to the outside world in 1978. The 1980s brought the first issuance of shares by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and a lively over-the-counter market. National stock markets were relaunched in Shanghai and Shenzhen in 1990 to 1991, while new guidance on the corporatisation and listing of SOEs was issued in 1992. The first overseas listing of a state enterprise came in October 1992 in New York, followed by the first SOE listing in Hong Kong in 1993. Corporate governance reform gained momentum in the late 1990s, but it was less a byproduct of the Asian Financial Crisis than a need to strengthen the governance of SOEs listing abroad. The early 2000s then brought a series of major reforms on independent directors, quarterly reporting and board governance aimed squarely at domestically listed firms.

A great deal has changed in China since then, with periods of intense policy focus on corporate governance followed by consolidation. In recent years, China’s equity market has undergone a renewed burst of internationalisation through Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Connect, relaxed rules for Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors, and the landmark inclusion of 234 leading A shares in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index in June 2018. While capital controls and other restrictions on foreign investment remain, there seems little reason to doubt that foreign portfolio investment will play an increasing role in China’s public and private securities markets in the foreseeable future.

Running parallel to market internationalisation, and facilitated by it, is a broadening of the scope of corporate governance to include a focus on environmental and social factors (“ESG”), and a deepening concern about climate change and environmental sustainability. Pension funds and investment managers in China are now encouraged by the government to look closely at ESG risks and opportunities in their investment process. And green finance has become big business in China, with green bond issuance growing steadily. Indeed, these themes are also part of the newly revised Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies (2018) from the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC); this is the first revision of the Code since 2002.

Turning point

China thus appears at a new turning point in its market development and application of corporate governance principles. While it is difficult to predict how this process will unfurl, we believe three broad developments would be beneficial:

-That unlisted and listed companies in China see corporate governance and ESG not merely as a compliance requirement, but as tools for enhancing organisational effectiveness and corporate performance over the longer term. This applies as much to entrepreneurial privately owned enterprises (POEs) as established SOEs. The view that good governance is not relevant or possible in young, innovative firms is misguided.

-That domestic institutional investors in China see corporate governance and ESG not only as tools for mitigating investment risk, but as a platform for enhancing the value of existing investments through active dialogue with investee companies. The process of engagement can also help investors differentiate between companies that take governance seriously and those which do not.

-That foreign institutional investors view corporate governance in China as something more nuanced than a division between “shareholder unfriendly” SOEs and “exciting but risky” POEs. We recommend foreign asset owners and managers spend more time on the ground in China and invest in studying China’s corporate governance system, if they are not already doing so.

Of course, there are many exceptions to these broad characterisations. It is possible to find companies which view governance as a learning journey—and they are not necessarily listed. Certain mainland asset managers have begun investigating how to integrate governance and ESG factors into their investment process. And there are a growing number of foreign investors, both boutique and mainstream, that have developed a deep understanding of the diversity among SOEs and POEs and which have achieved excellent investment returns from SOEs as well.

Not surprisingly, however, our research has found that significant gaps in communication and understanding do exist between foreign institutional investors and China listed companies. According to an original survey undertaken by ACGA for this report, a majority of foreign investor respondents (59%) admitted that they did not understand corporate governance in China. Only 10% answered in the affirmative, while another 31% felt they “somewhat” understood the system. Conversely, it appears that most China listed companies do not appreciate the challenges that foreign institutional investors face in navigating “corporate governance with Chinese characteristics”.

This report is written for both a domestic and international audience. Our aim is to describe in as fair and factual a manner as possible the system of corporate governance in China, highlighting what is unique, what looks the same but is different, and areas of genuine similarity with other major securities markets. The main part of the report focuses on “Chinese characteristics” and looks at the role of Party organisations/committees, the board of directors, supervisory boards, independent directors, SOEs vs POEs, and audit committees/auditing. Each chapter explains the current legal and regulatory basis for the governance institution described, the particular challenges that companies and investors face, and concludes with suggestions for next steps. Our intention has been to craft recommendations that are practical and anchored firmly in the current CG system in China—in other words, that are implementable by companies and institutional investors. We hope the suggestions, and indeed this report, will be viewed as a constructive contribution to the development of China’s capital market.

The remainder of this Introduction provides an overview of key macro results from our two surveys. We start with the good news—that a large proportion of foreign institutional investors and local companies are optimistic about China—then highlight the challenges both sides face in addressing governance issues. The following chapters draw upon additional material from the two surveys.

ACGA survey—The big picture

Are you optimistic?

The good news from our survey is that a sizeable proportion of both foreign investors (38% of respondents) and China listed companies (52%) are optimistic about the investment potential of the A share market over the next five to 10 years, as Figure 1.1 below shows. Only 21% of foreign investors are negative, while the remainder are neutral. Not surprisingly, only 15% of China respondents were negative, while almost one-third were neutral.

Do you agree with MSCI?

The picture diverges on the issue of whether MSCI was right to include A shares in its Emerging Markets Index in 2018: only 27% of foreign respondents agreed compared to 65% of Chinese respondents, as Figure 1.2, below, shows. Almost half the foreign respondents did not agree compared to a mere 12% for Chinese respondents. A similar proportion was neutral in both surveys.

Challenges—Foreign institutional investors

The investment process

Foreign investors face a range of challenges investing in China, the first of which is understanding the companies in which they invest. As Figure 1.3 below indicates, foreign investors do not rely solely on information provided by companies when making investment decisions, but utilise a range of additional sources. It appears that listed companies are not aware of this issue.

Company engagement

Globally, institutional investors seek to enter into dialogue with their investee companies. It is no different in China, as shown in Figure 1.4.

But the process is not easy.

And successful outcomes are fairly thin on the ground to date.

Common threads

Respondents gave a range of answers as to why the process of engagement was difficult and successful outcomes limited, but some common threads were discernible:

Language and communication: In addition to straightforward linguistic difficulties (ie, companies not speaking English, investors not speaking Chinese), the communication problem is sometimes cultural. As one person said, “Even though I am from China, it is hard to interpret hidden messages.”

Access: Getting access to companies can be difficult. Getting to meet the right senior-level person, such as a director or executive, can be even more challenging.

Investor relations (IR): While some IR teams are professional, many are not. As one respondent commented: “IR (managers) are not very well trained and some of them lack basic understanding or knowledge of corporate governance or even financial information.”

CG as compliance: A common complaint is that companies view CG as merely a compliance exercise. Some refuse to give “detailed answers beyond the party line”.

Non-alignment: There is a recurring feeling that the interests of controlling shareholders in SOEs are not aligned with minority shareholders. One investor commented on the “lack of responsiveness” to outside shareholder suggestions, adding that SOEs “wait for government to give the direction, not investors”.

Lack of understanding: There can be a significant gap in the awareness of CG and ESG principles.

Empathy for companies

Conversely, a few respondents expressed empathy for the position of companies. As one wrote: “There also appears to be an under appreciation by international investors of the differences in culture, political context, and the path and stage of economic development between China and the rest of the world. Any attempt at influencing changes without a reasonable understanding of these differences is likely to be ineffective and (may) at times lead to unintended consequences.”

Another explained some of the regulatory challenges facing listed companies: “With a few exceptions, both SOEs and POEs have to deal with stringent and ever-changing industry regulations and government policies.”

A third said that some engagement had been positive: “Generally, where I have had access to the right people, engagement has been constructive. I suspect this is a result of the companies already appreciating the value of good governance in attracting non-domestic investors.”

And perhaps the most positive comment of all: “A number of the Chinese companies we speak to, especially the industry leaders, already address ESG risks in their businesses. Most of them publish ESG reports annually, which help to set the benchmark for their industry and also to garner positive feedback from society and hence, end-customers. Some of such companies end up enjoying a pricing premium on their products once this positive brand equity has been established. This creates a virtuous cycle, where ESG becomes part of their corporate culture. They understand that for the long-term sustainability of their business, and for the benefits of all their stakeholders, such investment can only enhance their competitiveness.”

Brave new world of stewardship

Yet most investors still find engaging with companies a challenge. A further reason may be that China is one of only three major markets in Asia-Pacific that has not yet issued an “investor stewardship code”. Such codes push institutional investors to take CG and ESG more seriously, incorporate these concepts into their investment process, and help to encourage greater dialogue between listed companies and their shareholders (see Table 1.1, below). In recent years, the bar has been quickly raised on this issue in Asia and expectations have risen commensurately.

Without an explicit policy driving investor stewardship, it is unlikely that the average listed company will give proper weight to a dialogue with shareholders. As one foreign investor said: “Generally speaking, it is relatively easier to engage with bigger listed companies. SOEs and larger companies tend to be more responsive. SOEs have more incentive to do so following government guidelines and trends.”

A key question to ask is who within a company should be responsible for engaging with shareholders? The short answer is the board, as a group representing and accountable to shareholders. Indeed, on a positive note, our survey found that most Chinese listed companies do admit that the responsibility for talking to shareholders should not be placed solely on the investor relations (IR) team (see Figure 1.7 below). But given that delegating this task to IR remains a common practice, it would appear that there is an inconsistency between words and actions here.

Challenges—China listed companies

Some additional factors clearly play on the willingness of companies to take CG and ESG seriously, as Figures 1.8 and 1.9 below show.

Does the market reward good CG?

Only 27% of the respondents to our China listed company survey believe there is a close correlation between good corporate governance and company performance. Another 46% think they are “somewhat related”, while a quarter see no relationship. These results broadly align with the view common in most markets, including China, that only a minority of companies (usually the large caps) feel incentivised to improve their governance practices and that they will be rewarded by investors if they do so.

Even more concerning is the largely negative view on whether better governance helps a company to list.

As an aside, this might also help to explain why listed POEs in China are generally not seen as being a better investment proposition or as having better governance than SOEs—an issue we explore in Chapter 3.5.

Only 23% of foreign respondents said they preferred investing in POEs over SOEs, while two-thirds said they did not. Meanwhile, only 10% of China listed companies thought POEs were better governed than SOEs. Around one-third thought they were about the same, while 54% thought POEs were worse.

Even so, in a fast-growing market such as China, there is a risk in taking a static or one-dimensional view.

‘Companies will have to become more ESG aware’

We conclude this section with a wide-ranging comment from a China-based institutional investor on the need to see governance and ESG as a process:

Chinese companies are generally financial weaker than their more established peers in developed markets. This is a symptom of markets being at different stages of development. For Chinese companies, survival is the top priority. Once they have gained enough market share and accumulated a certain level of capital reserves, they will start to consider ESG issues. This will help them cement their market position and grow more healthily in the long term.

At the moment, we recognise that the cost of not practicing ESG is not high in China. But things are changing, especially on the environmental front. We can see that the government is very serious about closing down small players who are not compliant with emission standards. The quality of air, earth and water concerns the livelihood of every citizen, and we believe that there will be heightened enforcement of pollution laws.

Corporate governance is also improving as public shareholders get more actively involved in major corporate actions. Having said that, shareholder structures remain highly concentrated, especially for SOEs in China, and external forces may not be strong enough to ensure a proper division of power.

We see increasing numbers of entrepreneurs and companies more willing to give back to society and the challenge here is simply that philanthropy is quite new in China.

As society becomes more civilised and consumers become more aware of issues such as child labour and environmental pollution, Chinese companies will have to become more ESG aware and responsible.

Interview: ‘Character and quality of management is critical’

David Smith CFA, Head of Corporate Governance, Aberdeen Standard Investments Asia, Singapore

What is your view on investing in A shares?

We have an A share fund, so naturally, we have spent substantial time and effort getting comfortable with both the market and the companies. There are well-documented risks surrounding investing in China, but the market has obvious attractions China is leading the world in some of the sectors, like e-commerce, for example. As investors, we always have to balance return with macroeconomic risk, political risk, regulatory risk, and so on, and this is certainly the case for China.

What is your view on stock suspensions in China?

The situation is getting better but companies too often still choose to suspend given a pending “restructuring”, which protects potential investors at the expense of existing investors, something that can be incredibly frustrating given how long we can be locked up for. There is a general misunderstanding in China as to what suspension means: companies should only suspend when there is information asymmetry, not when there is uncertainty. We are paid to analyse and deal with uncertainty, and the market will find a price for it. If companies have to suspend whenever there is uncertainty, we won’t have a stock market in place.

In general, there are too many suspensions in China. If a company has a restructuring plan or a regulatory investigation is going on, it should just disclose this through an announcement; as long as everyone in the market knows the same information, the stock should keep trading.

The issue of price-sensitive information has already been taken care of by regulations around continuous disclosure, so a suspension is often not protecting anyone, it just removes liquidity for existing investors. This issue is exacerbated by the bizarre and unusual situation of dual-listed A/H share companies suspending on one exchange and not the other.

In developed markets, in contrast, suspensions of issuers lasting more than a month for whatever reason are very rare. Part of the issue is also that promoter shares might sometimes have been pledged, so promoters want to avoid a share price fall triggering a margin call.

What are the top CG issues you have observed in Chinese companies?

Entrepreneur risk (people risk) is the most obvious one, including related-party transaction risks, along with operational and execution risks. For Aberdeen, we never invest if we feel uncomfortable with the founder or management. Both the character and quality of the people inside the company is something we value a lot in our investment decision-making process.

Regulatory risk is another issue. Changes in regulations can affect not just SOEs but also POEs to different extents. For example, the recent regulatory change on the reinforcement of Party committees inside Chinese companies is not what foreign investors expected to see as the direction of corporate governance development in China.

Another issue is that given more and more onus put on independent directors, maybe we need to think about another way to elect them. The current situation involves voting for independent directors on their independence, rather than competence. However, “independence” can be easily gamed in Asia. Many independent directors are structurally independent but rely on the company for their living (pension), so investors are increasingly asking if/how they add value to board discussions.

What is your view on voting trends among China listed firms? Does voting lead to engagement

Not much has changed. Any voting against has tended to focus on resolutions like related-party transactions, or other corporate actions, rather than issues across the board.

Engagement is getting a little bit better in China. We have seen more and more companies listening to us, and dialogue is getting much better. Companies increasingly understand that we are not in China for the short-term and that our interests are aligned. That certainly helps.

Methodology

A tale of two surveys

The two surveys in this report, the “ACGA Foreign Institutional Investor Perceptions Survey 2017” and the “ACGA China Listed Company Perceptions Survey 2017”, were developed internally in the first half of 2017 and carried out over 21 July to 1 September of that year. They were distributed through ACGA’s global network of members and contacts, and by a number of supporting organisations both inside and outside China (see the Acknowledgements page for details).

Purpose

We decided to conduct a survey at the preliminary stage of this project for two main reasons. The first was to add a broader range of perspectives to the report and to complement the extensive research carried out by ACGA and our contributing authors.

The second was to develop new data on corporate governance in China. When we began researching this report, we found that much of the information on board structures and governance practices in China was out of date, incomplete or non-existent. We developed the survey to partially fill this gap. To complement this information, we turned to data providers such as Wind and Valueonline to provide raw data on which we could do original analysis—and we carried out our own reviews of specific governance practices among large listed companies.

Foreign Institutional Investor Perceptions Survey

The Foreign Institutional Investor Perceptions Survey contained 22 questions and focused on areas that we believe are relevant to China’s investment potential and governance. They can be divided into the following categories:

Macro questions, such as capital market development, MSCI inclusion, SOEs vs POEs, and mainland-listed vs overseas-listed firms.

Shareholder rights, including investor protection in China vs overseas.

Company governance, including corporate reporting, role of chairman, independent directors, supervisory boards.

Role of government, including appointment of chairmen, intervention in SOEs and POEs, the role of the Party organisation/committee.

Investor engagement with companies.

Several of the questions provided options for respondents to give detailed answers and, where relevant, these comments are incorporated into our text.

The survey was developed by ACGA in Q2 2017 and first tested with a select group of ACGA global investor members in June of that year. It was refined based on feedback received before being sent out electronically in July. The recipients were primarily drawn from among ACGA’s list of institutional investor members based in Asia and around the world. This was complemented by recipients from our supporting organisation membership networks.

In total, we received 155 complete and comparable responses. Partial responses were not counted. Based on information gathered about respondents’ titles, they fell into three broad groups: CEOs, directors, managing directors or partners; portfolio managers and analysts; and managers or specialists in CG, ESG or stewardship. A large proportion held senior roles in their organisations.

The total assets under management (AUM) of all respondents amounted to around US$40 trillion, with the range from US$20m to US$6 trillion. In other words, a mix of both boutique investment managers and large mainstream institutions.

China Listed Company Perceptions Survey

The China Listed Company Perceptions Survey contained 12 questions and likewise focused on areas that we believe are relevant to such companies, their directors and managers. While there were fewer questions in this survey, they covered similar categories as in our foreign survey, namely macro issues, company governance, role of government, and investor engagement.

We designed some questions to be identical to the Foreign Institutional Investor Survey, in order to allow direct comparisons between corporate and investor perspectives on the same issue.

We also asked some unique questions of companies, such as whether or not they see a close correlation between corporate governance and performance, and whether better governance helps a firm list its shares.

The survey recipients were drawn from among ACGA’s corporate membership base, as well as clients and contacts of supporting organisations.

In total, we received 182 complete responses from which we extracted the survey results. Most respondents held senior positions in their companies such as directors, executives, board secretaries and senior managers. Most of the companies represented have been listed in China for more than five years and have a market cap of more than Rmb5 billion (US$800m approx). Further demographic data on the two groups of respondents follows:

Foreign respondents

The foreign institutional investors who responded are mostly from the US, UK, Asia and the European Union, as shown in Figure 1.10 below. The response is consistent with the distribution of ACGA members by region. Investors from Australia, New Zealand, the Middle East and Canada also responded to the survey.

In terms of their global AUM, the vast majority of respondents have less than 1% invested in China A shares, while a significant minority have between 1% and 10%. Very few have more than 10% of their funds invested in China domestic listings, although interestingly a few have more than 50%. The latter would be smaller investment managers with a dedicated China focus, as shown in Figure 1.11.

The picture changes markedly when overseas-listed Chinese firms are taken into account: the majority of foreign respondents allocate between 1% to 10% of their global AUM to such companies and a sizeable proportion, about one-fifth, invest more than 10%.