Le texte a été publié en anglais. Vous pouvez le lire dans cette langue en cliquant sur le titre ci-dessous. Je vous invite à le faire puisque le texte original contient des tableaux et des statistiques que l’on ne retrouve pas dans ma version.

Afin de faciliter la compréhension, j’ai révisé la traduction électronique produite. Je crois que cette traduction est très acceptable.

Bonne lecture ! Vos commentaires sont les bienvenus.

Les conseils font l’objet des pressions croissantes pour démontrer leur pertinence à un moment où de multiples forces perturbatrices menacent les modèles d’affaires établis et créent de nouvelles possibilités d’innovation et de croissance. De plus en plus, les investisseurs s’attendent à ce que les conseils aient des processus significatifs en place pour renouveler leur adhésion et maximiser leur efficacité.

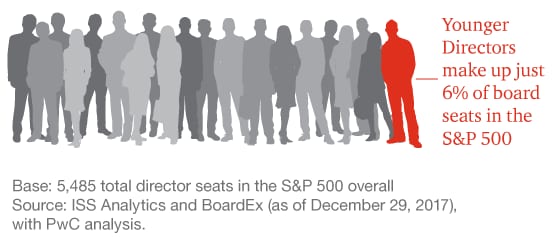

En conséquence, un nombre croissant « d’administrateurs de prochaine génération » sont nommés aux conseils d’administration à travers le monde. Beaucoup apportent des connaissances dans des domaines tels que la cybersécurité, l’IA (intelligence artificielle), l’apprentissage automatique et les technologies de l’industrie 4.0 ; d’autres ont une expérience directe de la transformation numérique, de la conception organisationnelle, de la connaissance du client ou de la communication sociale. Inévitablement, les experts de ces disciplines ont tendance à provenir d’une génération différente de celle de la majorité des membres du conseil d’administration.

Les jeunes administrateurs ont un impact sur le contenu et la dynamique du débat en salle de réunion. Ils incitent d’autres administrateurs à s’engager sur des sujets qui ne leur sont pas familiers et à apporter une approche et une perspective différentes au rôle. Tout comme les entreprises élargissent leur réflexion sur la valeur de la diversité et reconnaissent les avantages de la main-d’œuvre intergénérationnelle, les conseils bénéficient de recrutements d’administrateurs qui apportent non seulement une expertise foncièrement nécessaire, mais aussi une vision contemporaine de la façon dont les décisions affectent les parties prenantes — des employés et des fournisseurs aux clients et à la communauté. Ces administrateurs font face à un ensemble différent de défis en milieu de travail dans leurs rôles exécutifs ; en tant qu’administrateurs, ils peuvent rarement exprimer leurs préoccupations et leurs points de vue, autour de la table du conseil d’administration.

Les conseils qui choisissent sagement leurs jeunes administrateurs peuvent bénéficier grandement de leur présence. Cependant, il ne suffit pas d’amener de nouveaux administrateurs compétents dans la salle du conseil ; il est vital que les conseils les préparent au succès en combinant une intégration complète, une intégration réfléchie et une attitude ouverte, réceptive et respectueuse envers leurs contributions.

Nous avons interrogé un groupe de présidents de conseil d’administration et d’administrateurs de la prochaine génération sur plusieurs continents à propos de leur expérience de cette dernière phase de l’évolution des conseils d’administration.

Qu’y a-t-il pour la prochaine génération?

Avant de rejoindre le conseil d’administration d’une entreprise publique, il est important d’être clair sur la motivation. Pourquoi maintenant ; et pourquoi cette entreprise ? Être un administrateur non exécutif est un engagement important, et vous devez vous assurer que vous et le conseil d’administration considérez que c’est un investissement qui en vaut la peine. Nous constatons que la plupart des administrateurs next-gén sont motivés par trois choses : (1) le développement personnel. (2) la possibilité d’enrichir leur rôle exécutif avec de nouvelles idées et de nouvelles expériences acquises en tant qu’administrateur et (3) le désir de faire une contribution.

Un cadre qui commençait à se familiariser avec son propre conseil estimait qu’il était temps de se joindre à un conseil externe : « Je voulais élargir mon point de vue, acquérir des expériences différentes et voir une entreprise sous un autre angle. Je sentais que cela finirait par faire de moi un leader meilleur et plus efficace ». Une autre gestionnaire d’entreprise a souligné l’occasion unique d’apprendre d’autres personnes plus expérimentées qu’elle-même : « Je pourrais voir que je serais parmi les gens inspirants et que je serais exposé à un secteur différent, mais aussi, à une culture différente et à de nouvelles façons de faire des affaires. “Un troisième a décrit la décision de rejoindre un conseil comme” l’une des choses les plus utiles que j’ai fait dans ma vie ».

Les nouveaux administrateurs citent un certain nombre d’expériences et de compétences qu’ils espèrent acquérir en siégeant à un conseil, allant d’un style de leadership différent et travaillant avec une culture organisationnelle différente à l’apprentissage d’un nouveau secteur ou marché géographique.

Bien sûr, rejoindre un conseil d’administration doit être un exercice mutuellement bénéfique. « C’est utile pour moi parce que j’apprends sur la gouvernance, et sur le fonctionnement interne du conseil ». Je peux appliquer ce que j’apprends dans mon autre travail. Le conseil, quant à lui, obtient quelqu’un avec un ensemble différent de spécialités et une perspective légèrement plus fraîche ; ils ont quelqu’un qui veut être plus ouvert et plus direct, un peu plus non-conformiste par rapport aux autres membres du conseil.

Les présidents de conseil d’administration sont de plus en plus ouverts au recrutement de talents de prochaine génération, citant plusieurs raisons allant du besoin de compétences et de compétences spécifiques à des voix plus diverses à la table. Un président recherchait spécifiquement quelqu’un pour déplacer le centre du débat : « Un nouvel administrateur plus jeune peut voir un dilemme d’un point de vue différent, nous faisant réfléchir à deux fois. Je cherche une personne intègre qui est prête à parler ouvertement et à défier la gestion. Ce que je ne peux pas nécessairement attendre de ces personnes, bien sûr, c’est l’expérience d’avoir vu beaucoup de situations similaires sur 30-40 ans dans les affaires. C’est un compromis, et c’est l’une des raisons pour lesquelles la diversité des âges au sein du conseil est si importante. L’expertise des spécialistes doit être équilibrée avec l’expérience, et avec l’expérience vient un bon jugement ».

Préparation au rôle

Si vous êtes un dirigeant actif qui rejoint le conseil d’administration d’une entreprise publique, beaucoup de temps est en jeu (ainsi que votre réputation), vous devez donc être sûr que vous prenez la bonne décision. Un processus de vérification préalable approfondi offre non seulement cette sécurité, mais contribue également à accélérer votre préparation au rôle. « Au cours de mes entrevues, j’ai lu énormément de choses sur l’entreprise », a déclaré un administrateur récemment nommé. « J’ai regardé les appels des analystes, j’ai lu les documents de la SEC et j’ai posé beaucoup de questions, en particulier sur la dynamique du conseil. Ils m’ont fait rencontrer tous les membres du conseil d’administration et j’ai pu voir comment ils se parlaient entre eux ».

Il est important d’avoir une compréhension claire de ce que le conseil recherche et de la façon dont vos antécédents et votre expérience ajouteront de la valeur dans le contexte de l’entreprise. Par exemple, bien que les membres du conseil les plus séniors puissent avoir un aperçu raisonnable de la perturbation de l’entreprise, ils n’auront pas d’expérience pratique d’une initiative de transformation numérique. Vous êtes peut-être parfaitement placé pour fournir ces connaissances de première main, mais il se peut que le président du conseil d’administration veuille bien faire face à certaines difficultés, ait appris à relever le défi technologique d’un point de vue commercial et sache quel type de questions poser. Seule une due diligence approfondie révélera si vos attentes sont alignées avec celles du conseil et vous permettront de procéder en toute confiance.

Embarquement (Onboarding)

L’une des choses les plus courantes que nous entendons des administrateurs de prochaine génération est qu’ils auraient aimé un processus d’intégration plus approfondi avant leur première réunion — c’est quelque chose que les conseils d’administration doivent clairement aborder. Il revient souvent aux nouveaux administrateurs de prendre l’initiative et de concevoir un programme qui les aidera à s’intégrer dans l’entreprise. « Une grande partie de l’immersion dont j’ai eu besoin est venue des étapes que j’ai suivies moi-même », a déclaré un administrateur qui estimait que rencontrer quelques dirigeants et présidents de comité du conseil ainsi qu’une lecture du matériel fourni par le secrétaire de la société constituait une préparation insuffisante.

Un bon programme d’initiation comprendra des présentations de la direction sur le modèle d’affaires, la rentabilité et la performance ; visites de site ; et des réunions avec des conseillers externes tels que des comptables, des banquiers et des courtiers. Assister avec le responsable des relations avec les investisseurs pour revoir les perspectives des investisseurs et des analystes peut aussi être utile.

Les administrateurs de la prochaine génération ont demandé à rencontrer les chefs d’entreprise pour un examen plus détaillé d’une filiale ou d’une activité particulière où leur propre expérience est particulièrement pertinente. Dans une entreprise de vente au détail, par exemple, il serait logique de rencontrer le responsable du merchandising d’un magasin phare pour se familiariser avec le positionnement des produits et l’expérience client.

Le temps passé avec le PDG pour en apprendre davantage sur l’entreprise est essentiel. La plupart des chefs d’entreprise seront ravis de faire en sorte que le nouvel administrateur puisse voir directement les principaux projets et rencontrer les personnes qui les dirigent, ainsi que passer du temps avec d’autres membres de l’équipe de la haute direction. « Ils étaient complètement ouverts à la possibilité de rencontrer d’autres personnes, mais cela ne faisait pas partie du programme d’initiation formel. J’ai trouvé ces conversations les plus éclairantes parce que je me suis simplement rapproché de l’entreprise et du travail. »

Un président d’une société de produits de consommation a ajouté une touche intéressante à l’intégration d’un nouvel administrateur nommé pour son expérience de leadership en matière de commerce électronique. Il a invité la nouvelle recrue à faire une présentation à toute l’équipe de direction au sujet de son propre cheminement. « Le genre de perturbation et la vitesse à laquelle fonctionne sa société en ligne étaient stupéfiants, et cet exercice s’est avéré une source d’apprentissage pour le conseil d’administration et l’équipe de direction », a déclaré le président. « Cela a également renforcé sa crédibilité auprès du reste du conseil ».

Faire la transition à un rôle d’administrateur non exécutif

La plupart des administrateurs de la prochaine génération comprennent qu’ils devront aborder les responsabilités de leur conseil d’une manière différente d’un rôle exécutif, mais la plupart sous-estiment les difficultés à faire cette transition dans la pratique.

Il est important d’être en mesure de faire la distinction entre les questions sur lesquelles seul le conseil peut se prononcer (par exemple, la relève du chef de la direction) et les sujets que le conseil doit laisser à la direction (questions opérationnelles). La stratégie est un domaine où, dans la plupart des marchés, le conseil d’administration et la direction ont tendance à collaborer étroitement, mais il y a beaucoup d’autres moyens où les administrateurs de la prochaine génération peuvent apporter leur expertise particulière.

Cependant, il faut du temps pour apprendre comment ajouter de la valeur aux discussions du conseil sans pour autant saper l’autorité de la direction. L’écoute et l’apprentissage sont un aspect crucial pour gagner le respect et la crédibilité auprès du reste du conseil. « Il faut être très conscient du moment où il faut intervenir, quand il est nécessaire d’insister sur un sujet difficile, et quand il faut prendre du recul », explique un administrateur. « La compétence consiste à poser la bonne question de la bonne façon — à ne pas affaiblir ou à décourager la direction, mais à les encourager à voir les choses un peu différemment ».

En tant qu’administrateur non exécutif, vous devez vous engager à un niveau supérieur et de manière plus détachée que dans votre rôle exécutif. Avec des réunions mensuelles ou bimestrielles, il peut être difficile de déterminer si vous ajoutez de la valeur, ou même à quoi ressemble la valeur, surtout lorsque votre travail régulier implique de prendre la responsabilité d’une exécution de haute qualité. En tant qu’administrateur non exécutif, vous pouvez voir des choses qui doivent être prises en compte et vouloir vous impliquer plus activement, mais vous devez faire confiance en la capacité de l’équipe de direction à le faire. « J’avais l’impression que le conseil d’administration pourrait être un peu plus engagé. Nous avons des zones très précises dans lesquelles nous sommes censés contribuer à orienter les décisions et les actions, et il y en a d’autres où nous sommes plus consultatifs ; c’est une question de trouver le bon équilibre ».

Cependant, le travail des administrateurs de prochaine génération ne commence pas et ne se termine pas avec les réunions du conseil d’administration. Beaucoup interagiront avec la direction en dehors des réunions. Un directeur britannique nommé pour son expertise numérique prend le temps de se mettre à jour avec l’équipe numérique de l’entreprise lorsqu’elle est à New York « pour savoir à quoi ils travaillent, comprendre ce qui les motive et quelles sont leurs préoccupations ». Un nouvel administrateur indépendant a été invité par le PDG (CEO) à passer une journée avec l’équipe de management du développement de l’entreprise, après quoi il a passé en revue l’expérience client. « J’ai reçu des commentaires très clairs, mais je me suis contenté de l’envoyer au chef de la direction, pas à l’équipe que j’ai rencontrée ou à un autre membre du conseil ». Offrir de l’aide à l’équipe de direction de façon informelle.

Votre rôle n’est pas nécessairement de comprendre les problèmes, mais de proposer des idées et de poser des questions à l’équipe de direction.

Obtenir de la rétroaction

Les administrateurs de prochaine génération qui sont habitués à recevoir des commentaires dans leur capacité de direction peuvent avoir du mal à s’adapter à un rôle où il est moins facilement disponible. « La rétroaction est la chose la plus difficile à laquelle je me suis attaqué », explique un administrateur. « Avec votre propre entreprise, c’est un succès ou pas. Si vous êtes un employé, on vous dit si vous faites du bon travail. Ce n’est pas le cas sur un conseil ».

Les nouveaux administrateurs doivent identifier une personne avec laquelle ils se sentent à l’aise et qui peut leur offrir un aperçu de certaines des règles non écrites du conseil. Certains préfèrent une relation de mentorat plus formelle avec un membre du conseil d’administration, mais cette idée ne plaît pas à tout le monde. Des vérifications régulières auprès du président du conseil (et du chef de la direction) les aideront à évaluer leur rendement et à apprendre comment ils peuvent offrir une contribution plus utile.

Au-delà de la rétroaction individuelle informelle, le conseil peut avoir un processus pour fournir une rétroaction à chaque administrateur dans le cadre de l’auto-évaluation annuelle du conseil. Sur les conseils où cette pratique est en place, les administrateurs de la prochaine génération ont tendance à être très à l’aise avec elle et à accueillir les commentaires. S’il n’y a pas de processus de rétroaction individuelle des administrateurs en place, l’administrateur de la prochaine génération peut servir de catalyseur pour établir cette saine pratique en s’enquérant directement à ce sujet.

Le rôle du président du conseil

Les présidents de conseil ont une influence significative sur le succès des administrateurs de prochaine génération dans le rôle. Il peut être difficile d’arriver à un conseil qui compte beaucoup d’administrateurs plus âgés et plus expérimentés, en particulier s’il existe une dynamique « collégiale » établie de longue date. Le président a la double tâche de guider le nouvel administrateur, tout en s’assurant que les autres membres du conseil restent ouverts aux nouvelles idées et perspectives que celui-ci apporte au conseil. Cela peut impliquer de travailler dur pour encourager les relations à se développer à un niveau personnel, ce qui permettra ensuite d’émettre des points de vue divergents, et même dissidents sur le plan professionnel.

Un président peut faire un certain nombre de choses pour soutenir l’administrateur de la prochaine génération, par exemple : s’intéresser de près au processus d’intégration ; fournir un encadrement sur la meilleure façon de représenter les intérêts des investisseurs ; offrir des commentaires constructifs après les réunions ; et encourager le nouvel administrateur à se tenir à l’écart plutôt que de jouer la carte de la sécurité et à simplement s’aligner sur la culture existante du conseil d’administration. Comme l’a dit un président : « Certains conseils se méfient d’un nouvel administrateur qui pense différemment et qui menace, bien que respectueusement, de faire bouger les choses. Mais parfois, vous avez besoin que le nouvel administrateur perturbe le conseil avec des idées nouvelles, acceptant que cela puisse entraîner un changement culturel. C’est mon travail de laisser cela se produire ». Cela dit, si un nouvel administrateur est en désaccord avec certains éléments contenus dans la documentation du conseil d’administration ou s’il ne comprend pas, il serait sage d’en discuter avec le président du conseil en premier lieu.

Pour le nouvel administrateur, l’adaptation à la structure et à la formalité des réunions du conseil d’administration signifie adopter une approche mesurée et s’inspirer de la décision du président, en particulier à contre-courant. « Bien que je n’aie assisté qu’à trois réunions, je teste les barrières qui font que je peux être ouvert et direct, tout en en apprenant davantage sur l’entreprise », rapporte un administrateur. Un autre a défendu une position non partagée par la majorité du conseil d’administration, convaincu que le président est heureux de donner une tribune à ses opinions. Vous devez être respectueux et faire valoir votre point de vue et vos arguments, mais si ceux-ci ne prévalent pas, c’est bien aussi. Bien sûr, si cela devient une question de principe, vous êtes toujours libre de démissionner, n’est-ce pas ?

Vers un nouveau genre de conseil

Au fur et à mesure que les entreprises relèvent de nouveaux défis et qu’une jeune génération de cadres issus de milieux très différents accède à des postes d’administrateurs indépendants, les conseils d’administration devront trouver le bon équilibre entre expérience et pertinence. Ils devront également devenir plus dynamiques en matière de composition, de diversité, de discussion et d’occupation. Les administrateurs de longue date qui s’intéressent à la gouvernance et à la gestion des risques côtoieront des représentants de la prochaine génération nommés pour leur excellente connaissance du domaine ou leur expérience en temps réel des environnements transformationnels, mais le mandat de ces administrateurs sera probablement plus court que la moyenne actuelle.

Les conseils doivent être réalistes quant à la durée du mandat d’un candidat de la prochaine génération. Ils doivent également réfléchir soigneusement à la question de savoir si cet administrateur se sentirait moins isolé et plus efficace s’il était accompagné par un autre administrateur d’un âge et d’un passé similaires. « En tant que femme, j’ai été une minorité tout au long de ma carrière, donc c’est étrange d’être une minorité à cause de mon expertise numérique », a déclaré une administratrice. Tout comme la présence d’autres femmes au sein du conseil d’administration réduit le fardeau d’une femme administratrice, il y a lieu de nommer deux ou plusieurs administrateurs de la nouvelle génération.

Les conseils d’administration résolus à rester au fait des problèmes critiques affectant leurs entreprises devraient considérer les avantages potentiels de nommer au moins un administrateur de la prochaine génération, non seulement pour leur expertise, mais aussi pour leur capacité à apporter une pensée alternative et des perspectives multipartites dans la salle du conseil. Soutenus par un président du conseil attentif et par des administrateurs ouverts d’esprit, les administrateurs de la prochaine génération peuvent avoir un impact positif et durable sur l’efficacité du conseil en cette période de changement sans précédent.