Les conseils d’administration sont de plus en plus confrontés à l’exigence d’évaluer l’efficacité de leur fonctionnement par le biais d’une évaluation annuelle du CA, des comités et des administrateurs.

En fait, le NYSE exige depuis dix ans que les conseils procèdent à leur évaluation et que les résultats du processus soient divulgués aux actionnaires. Également, les investisseurs institutionnels et les activistes demandent de plus en plus d’informations au sujet du processus d’évaluation.

Les résultats de l’évaluation peuvent être divulgués de plusieurs façons, notamment dans les circulaires de procuration et sur le site de l’entreprise.

On recommande de modifier les méthodes et les paramètres de l’évaluation à chaque trois ans afin d’éviter la routine susceptible de s’installer si les administrateurs remplissent les mêmes questionnaires, gérés par le président du conseil. De plus, l’objectif de l’évaluation est sujet à changement (par exemple, depuis une décennie, on accorde une grande place à la cybersécurité).

C’est au comité de gouvernance que revient la supervision du processus d’évaluation du conseil d’administration. L’article décrit quatre méthodes fréquemment utilisées.

(1) Les questionnaires gérés par le comité de gouvernance ou une personne externe

(3) les entretiens individuels avec les administrateurs sur des thèmes précis par le président du conseil, le président du comité de gouvernance ou un expert externe.

(4) L’évaluation des contributions de chaque administrateur par la méthode d’auto-évaluation et par l’évaluation des pairs.

Chaque approche a ses particularités et la clé est de varier les façons de faire périodiquement. On constate également que beaucoup de sociétés cotées utilisent les services de spécialistes pour les aider dans leurs démarches.

La quasi-totalité des entreprises du S&P 500 divulgue le processus d’évaluation utilisé pour améliorer leur efficacité. L’article présente deux manières de diffuser les résultats du processus d’évaluation.

(1) Structuré, c’est-à-dire un format qui précise — qui évalue quoi ; la fréquence de l’évaluation ; qui supervise les résultats ; comment le CA a-t-il agi eu égard aux résultats de l’opération d’évaluation.

(2) Information axée sur les résultats — les grandes conclusions ; les facteurs positifs et les points à améliorer ; un plan d’action visant à corriger les lacunes observées.

Voici trois articles parus sur mon blogue qui abordent le sujet de l’évaluation :

More than ten years have passed since the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) began requiring annual evaluations for boards of directors and “key” committees (audit, compensation, nominating/governance), and many NASDAQ companies also conduct these evaluations annually as a matter of good governance. [1] With boards now firmly in the routine of doing annual evaluations, one challenge (as with any recurring activity) is to keep the process fresh and productive so that it continues to provide the board with valuable insights. In addition, companies are increasingly providing, and institutional shareholders are increasingly seeking, more information about the board’s evaluation process. Boards that have implemented a substantive, effective evaluation process will want information about their work in this area to be communicated to shareholders and potential investors. This can be done in a variety of ways, including in the annual proxy statement, in the governance or investor information section on the corporate website, and/or as part of shareholder engagement outreach.

To assist companies and their boards in maximizing the effectiveness of the evaluation process and related disclosures, this post provides an overview of several frequently used methods for conducting evaluations of the full board, board committees and individual directors. It is our experience that using a variety of methods, with some variation from year to year, results in more substantive and useful evaluations. This post also discusses trends and considerations relating to disclosures about board evaluations. We close with some practical tips for boards to consider as they look ahead to their next annual evaluation cycle.

Common Methods of Board Evaluation

As a threshold matter, it is important to note that there is no one “right” way to conduct board evaluations. There is room for flexibility, and the boards and committees we work with use a variety of methods. We believe it is good practice to “change up” the board evaluation process every few years by using a different format in order to keep the process fresh. Boards have increasingly found that year-after-year use of a written questionnaire, with the results compiled and summarized by a board leader or the corporate secretary for consideration by the board, becomes a routine exercise that produces few new insights as the years go by. This has been the most common practice, and it does respond to the NYSE requirement, but it may not bring as much useful information to the board as some other methods.

Doing something different from time to time can bring new perspectives and insights, enhancing the effectiveness of the process and the value it provides to the board. The evaluation process should be dynamic, changing from time to time as the board identifies practices that work well and those that it finds less effective, and as the board deals with changing expectations for how to meet its oversight duties. As an example, over the last decade there have been increasing expectations that boards will be proactive in oversight of compliance issues and risk (including cyber risk) identification and management issues.

Three of the most common methods for conducting a board or committee evaluation are: (1) written questionnaires; (2) discussions; and (3) interviews. Some of the approaches outlined below reflect a combination of these methods. A company’s nominating/governance committee typically oversees the evaluation process since it has primary responsibility for overseeing governance matters on behalf of the board.

1. Questionnaires

The most common method for conducting board evaluations has been through written responses to questionnaires that elicit information about the board’s effectiveness. The questionnaires may be prepared with the assistance of outside counsel or an outside advisor with expertise in governance matters. A well-designed questionnaire often will address a combination of substantive topics and topics relating to the board’s operations. For example, the questionnaire could touch on major subject matter areas that fall under the board’s oversight responsibility, such as views on whether the board’s oversight of critical areas like risk, compliance and crisis preparedness are effective, including whether there is appropriate and timely information flow to the board on these issues. Questionnaires typically also inquire about whether board refreshment mechanisms and board succession planning are effective, and whether the board is comfortable with the senior management succession plan. With respect to board operations, a questionnaire could inquire about matters such as the number and frequency of meetings, quality and timeliness of meeting materials, and allocation of meeting time between presentation and discussion. Some boards also consider their efforts to increase board diversity as part of the annual evaluation process.

Many boards review their questionnaires annually and update them as appropriate to address new, relevant topics or to emphasize particular areas. For example, if the board recently changed its leadership structure or reallocated responsibility for a major subject matter area among its committees, or the company acquired or started a new line of business or experienced recent issues related to operations, legal compliance or a breach of security, the questionnaire should be updated to request feedback on how the board has handled these developments. Generally, each director completes the questionnaire, the results of the questionnaires are consolidated, and a written or verbal summary of the results is then shared with the board.

Written questionnaires offer the advantage of anonymity because responses generally are summarized or reported back to the full board without attribution. As a result, directors may be more candid in their responses than they would be using another evaluation format, such as a face-to-face discussion. A potential disadvantage of written questionnaires is that they may become rote, particularly after several years of using the same or substantially similar questionnaires. Further, the final product the board receives may be a summary that does not pick up the nuances or tone of the views of individual directors.

In our experience, increasingly, at least once every few years, boards that use questionnaires are retaining a third party, such as outside counsel or another experienced facilitator, to compile the questionnaire responses, prepare a summary and moderate a discussion based on the questionnaire responses. The desirability of using an outside party for this purpose depends on a number of factors. These include the culture of the board and, specifically, whether the boardroom environment is one in which directors are comfortable expressing their views candidly. In addition, using counsel (inside or outside) may help preserve any argument that the evaluation process and related materials are privileged communications if, during the process, counsel is providing legal advice to the board.

In lieu of asking directors to complete written questionnaires, a questionnaire could be distributed to stimulate and guide discussion at an interactive full board evaluation discussion.

2. Group Discussions

Setting aside board time for a structured, in-person conversation is another common method for conducting board evaluations. The discussion can be led by one of several individuals, including: (a) the chairman of the board; (b) an independent director, such as the lead director or the chair of the nominating/governance committee; or (c) an outside facilitator, such as a lawyer or consultant with expertise in governance matters. Using a discussion format can help to “change up” the evaluation process in situations where written questionnaires are no longer providing useful, new information. It may also work well if there are particular concerns about creating a written record.

Boards that use a discussion format often circulate a list of discussion items or topics for directors to consider in advance of the meeting at which the discussion will occur. This helps to focus the conversation and make the best use of the time available. It also provides an opportunity to develop a set of topics that is tailored to the company, its business and issues it has faced and is facing. Another approach to determining discussion topics is to elicit directors’ views on what should be covered as part of the annual evaluation. For example, the nominating/governance could ask that each director select a handful of possible topics for discussion at the board evaluation session and then place the most commonly cited topics on the agenda for the evaluation.

A discussion format can be a useful tool for facilitating a candid exchange of views among directors and promoting meaningful dialogue, which can be valuable in assessing effectiveness and identifying areas for improvement. Discussions allow directors to elaborate on their views in ways that may not be feasible with a written questionnaire and to respond in real time to views expressed by their colleagues on the board. On the other hand, they do not provide an opportunity for anonymity. In our experience, this approach works best in boards with a high degree of collegiality and a tradition of candor.

3. Interviews

Another method of conducting board evaluations that is becoming more common is interviews with individual directors, done in-person or over the phone. A set of questions is often distributed in advance to help guide the discussion. Interviews can be done by: (a) an outside party such as a lawyer or consultant; (b) an independent director, such as the lead director or the chair of the nominating/governance committee; or (c) the corporate secretary or inside counsel, if directors are comfortable with that. The party conducting the interviews generally summarizes the information obtained in the interview process and may facilitate a discussion of the information obtained with the board.

In our experience, boards that have used interviews to conduct their annual evaluation process generally have found them very productive. Directors have observed that the interviews yielded rich feedback about the board’s performance and effectiveness. Relative to other types of evaluations, interviews are more labor-intensive because they can be time-consuming, particularly for larger boards. They also can be expensive, particularly if the board retains an outside party to conduct the interviews. For these reasons, the interview format generally is not one that is used every year. However, we do see a growing number of boards taking this path as a “refresher”—every three to five years—after periods of using a written questionnaire, or after a major event, such as a corporate crisis of some kind, when the board wants to do an in-depth “lessons learned” analysis as part of its self-evaluation. Interviews also offer an opportunity to develop a targeted list of questions that focuses on issues and themes that are specific to the board and company in question, which can contribute further to the value derived from the interview process.

For nominating/governance committees considering the use of an interview format, one key question is who will conduct the interviews. In our experience, the most common approach is to retain an outside party (such as a lawyer or consultant) to conduct and summarize interviews. An outside party can enhance the effectiveness of the process because directors may be more forthcoming in their responses than they would if another director or a member of management were involved.

Individual Director Evaluations

Another practice that some boards have incorporated into their evaluation process is formal evaluations of individual directors. In our experience, these are not yet widespread but are becoming more common. At companies where the nominating/governance committee has a robust process for assessing the contributions of individual directors each year in deciding whether to recommend them for renomination to the board, the committee and the board may conclude that a formal evaluation every year is unnecessary. Historically, some boards have been hesitant to conduct individual director evaluations because of concerns about the impact on board collegiality and dynamics. However, if done thoughtfully, a structured process for evaluating the performance of each director can result in valuable insights that can strengthen the performance of individual directors and the board as a whole.

As with board and committee evaluations, no single “best practice” has emerged for conducting individual director evaluations, and the methods described above can be adapted for this purpose. In addition, these evaluations may involve directors either evaluating their own performance (self-evaluations), or evaluating their fellow directors individually and as a group (peer evaluations). Directors may be more willing to evaluate their own performance than that of their colleagues, and the utility of self-evaluations can be enhanced by having an independent director, such as the chairman of the board or lead director, or the chair of the nominating/governance committee, provide feedback to each director after the director evaluates his or her own performance. On the other hand, peer evaluations can provide directors with valuable, constructive comments. Here, too, each director’s evaluation results typically would be presented only to that director by the chairman of the board or lead director, or the chair of the nominating/governance committee. Ultimately, whether and how to conduct individual director evaluations will depend on a variety of factors, including board culture.

Disclosures about Board Evaluations

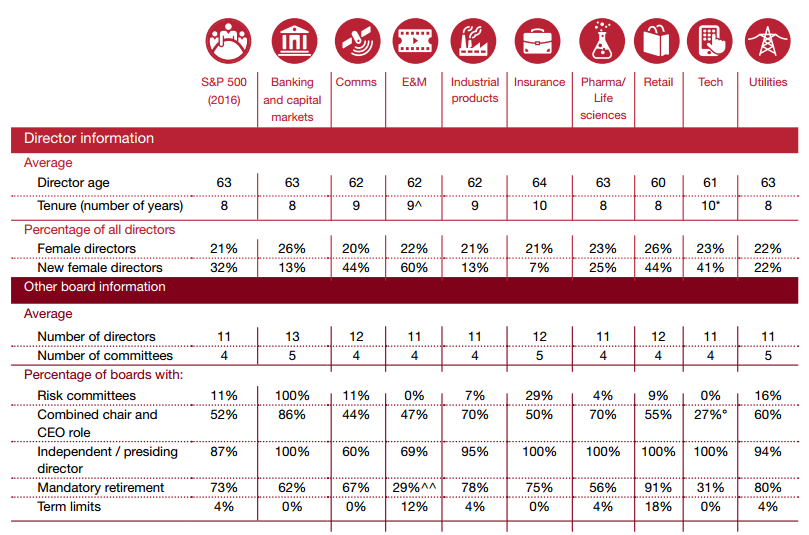

Many companies discuss the board evaluation process in their corporate governance guidelines. [2] In addition, many companies now provide disclosure about the evaluation process in the proxy statement, as one element of increasingly robust proxy disclosures about their corporate governance practices. According to the 2015 Spencer Stuart Board Index, all but 2% of S&P 500 companies disclose in their proxy statements, at a minimum, that they conduct some form of annual board evaluation.

In addition, institutional shareholders increasingly are expressing an interest in knowing more about the evaluation process at companies where they invest. In particular, they want to understand whether the board’s process is a meaningful one, with actionable items emerging from the evaluation process, and not a “check the box” exercise. In the United Kingdom, companies must report annually on their processes for evaluating the performance of the board, its committees and individual directors under the UK Corporate Governance Code. As part of the code’s “comply or explain approach,” the largest companies are expected to use an external facilitator at least every three years (or explain why they have not done so) and to disclose the identity of the facilitator and whether he or she has any other connection to the company.

In September 2014, the Council of Institutional Investors issued a report entitled Best Disclosure: Board Evaluation (available here), as part of a series of reports aimed at providing investors and companies with approaches to and examples of disclosures that CII considers exemplary. The report recommended two possible approaches to enhanced disclosure about board evaluations, identified through an informal survey of CII members, and included examples of disclosures illustrating each approach. As a threshold matter, CII acknowledged in the report that shareholders generally do not expect details about evaluations of individual directors. Rather, shareholders “want to understand the process by which the board goes about regularly improving itself.” According to CII, detailed disclosure about the board evaluation process can give shareholders a “window” into the boardroom and the board’s capacity for change.

The first approach in the CII report focuses on the “nuts and bolts” of how the board conducts the evaluation process and analyzes the results. Under this approach, a company’s disclosures would address: (1) who evaluates whom; (2) how often the evaluations are done; (3) who reviews the results; and (4) how the board decides to address the results. Disclosures under this approach do not address feedback from specific evaluations, either individually or more generally, or conclusions that the board has drawn from recent self-evaluations. As a result, according to CII, this approach can take the form of “evergreen” proxy disclosure that remains similar from year to year, unless the evaluation process itself changes.

The second approach focuses more on the board’s most recent evaluation. Under this approach, in addition to addressing the evaluation process, a company’s disclosures would provide information about “big-picture, board-wide findings and any steps for tackling areas identified for improvement” during the board’s last evaluation. The disclosures would identify: (1) key takeaways from the board’s review of its own performance, including both areas where the board believes it functions effectively and where it could improve; and (2) a “plan of action” to address areas for improvement over the coming year. According to CII, this type of disclosure is more common in the United Kingdom and other non-U.S. jurisdictions.

Also reflecting a greater emphasis on disclosure about board evaluations, proxy advisory firm Institutional Shareholder Services Inc. (“ISS”) added this subject to the factors it uses in evaluating companies’ governance practices when it released an updated version of “QuickScore,” its corporate governance benchmarking tool, in Fall 2014. QuickScore views a company as having a “robust” board evaluation policy where the board discloses that it conducts an annual performance evaluation, including evaluations of individual directors, and that it uses an external evaluator at least every three years (consistent with the approach taken in the UK Corporate Governance Code). For individual director evaluations, it appears that companies can receive QuickScore “credit” in this regard where the nominating/governance committee assesses director performance in connection with the renomination process.

What Companies Should Do Now

As noted above, there is no “one size fits all” approach to board evaluations, but the process should be viewed as an opportunity to enhance board, committee and director performance. In this regard, a company’s nominating/governance committee and board should periodically assess the evaluation process itself to determine whether it is resulting in meaningful takeaways, and whether changes are appropriate. This includes considering whether the board would benefit from trying new approaches to the evaluation process every few years.

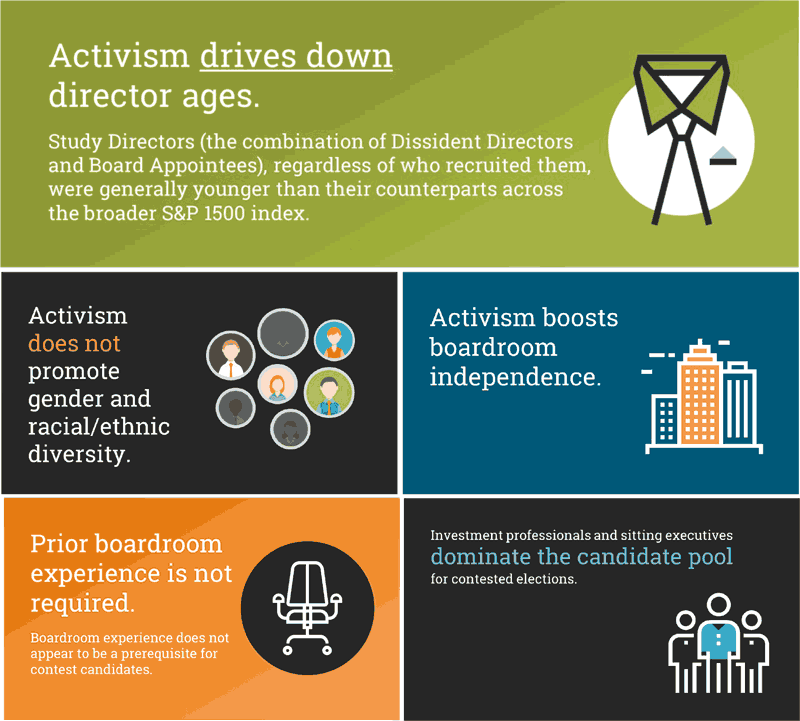

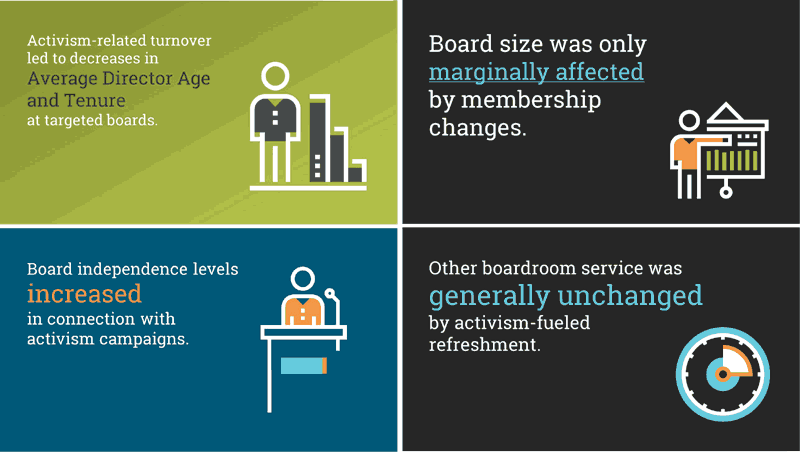

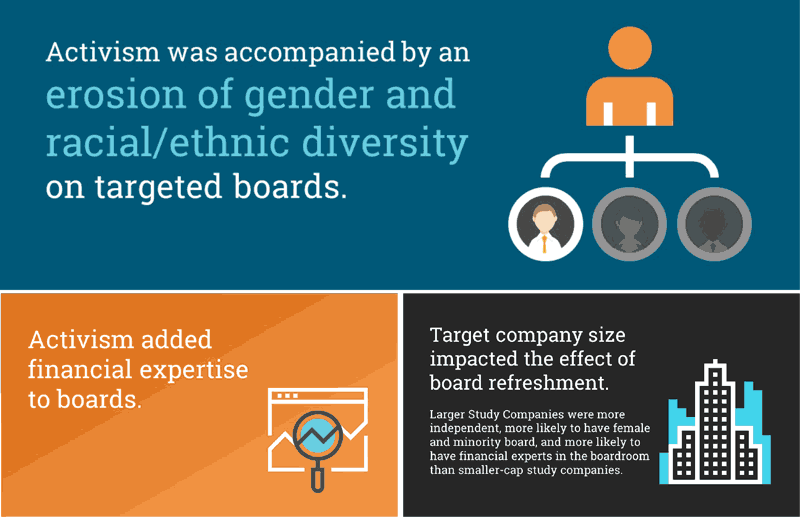

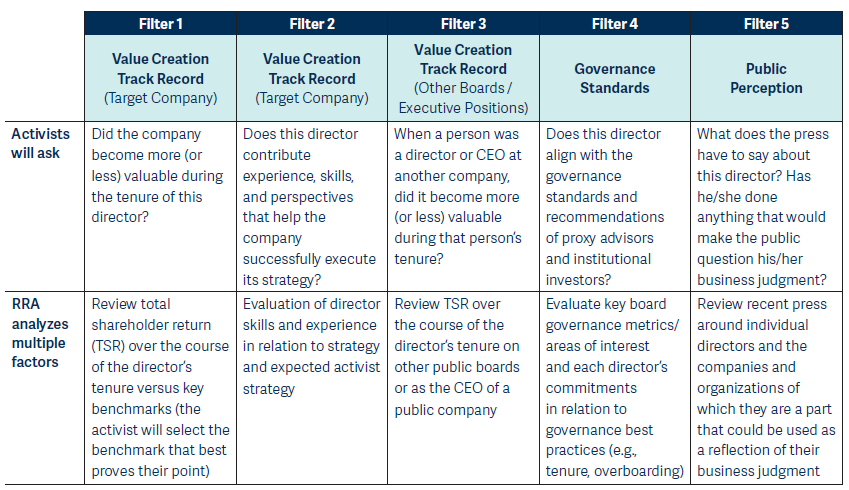

Factors to consider in deciding what evaluation format to use include any specific objectives the board seeks to achieve through the evaluation process, aspects of the current evaluation process that have worked well, the board’s culture, and any concerns directors may have about confidentiality. And, we believe that every board should carefully consider “changing up” the evaluation process used from time to time so that the exercise does not become rote. What will be the most beneficial in any given year will depend on a variety of factors specific to the board and the company. For the board, this includes considerations of board refreshment and tenure, and developments the board may be facing, such as changes in board or committee leadership. Factors relevant to the company include where the company is in its lifecycle, whether the company is in a period of relative stability, challenge or transformation, whether there has been a significant change in the company’s business or a senior management change, whether there is activist interest in the company and whether the company has recently gone through or is going through a crisis of some kind. Specific items that nominating/governance committees could consider as part of maintaining an effective evaluation process include:

- Revisit the content and focus of written questionnaires. Evaluation questionnaires should be updated each time they are used in order to reflect significant new developments, both in the external environment and internal to the board.

- “Change it up.” If the board has been using the same written questionnaire, or the same evaluation format, for several years, consider trying something new for an upcoming annual evaluation. This can bring renewed vigor to the process, reengage the participants, and result in more meaningful feedback.

- Consider whether to bring in an external facilitator. Boards that have not previously used an outside party to assist in their evaluations should consider whether this would enhance the candor and overall effectiveness of the process.

- Engage in a meaningful discussion of the evaluation results. Unless the board does its evaluation using a discussion format, there should be time on the board’s agenda to discuss the evaluation results so that all directors have an opportunity to hear and discuss the feedback from the evaluation.

- Incorporate follow-up into the process. Regardless of the evaluation method used, it is critical to follow up on issues and concerns that emerge from the evaluation process. The process should include identifying concrete takeaways and formulating action items to address any concerns or areas for improvement that emerge from the evaluation. Senior management can be a valuable partner in this endeavor, and should be briefed as appropriate on conclusions reached as a result of the evaluation and related action items. The board also should consider its progress in addressing these items.

- Revisit disclosures. Working with management, the nominating/governance committee and the board should discuss whether the company’s proxy disclosures, investor and governance website information and other communications to shareholders and potential investors contain meaningful, current information about the board evaluation process.