Voici un article très intéressant sur les tendances en évaluation des CA à l’échelle internationale.

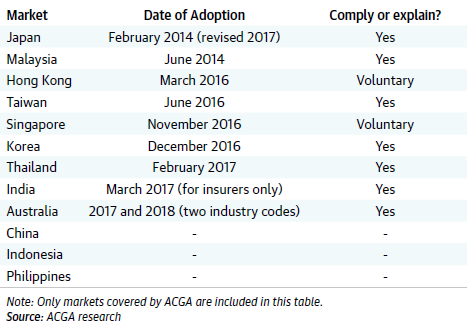

Les auteurs, Mark Fenwick* et Erik P. M. Vermeulen, ont étudié l’état de la situation de l’évaluation des conseils dans 20 juridictions différentes qu’ils ont classifiées en 5 groupes, allant d’absence de législation, à des réglementations détaillées et explicites.

Dans l’ensemble, l’étude montre que les juridictions qui sont explicites eu égard aux meilleures pratiques en matière d’évaluation des conseils sont plus susceptibles d’adopter des processus d’évaluation efficaces. La législation et la réglementation ont un grand pouvoir d’influence sur les pratiques exemplaires.

Les auteurs retiennent un certain nombre de constats sur les meilleures pratiques en évaluation des CA :

(1) Although there is “no one-size-fits-all” solution, and the design of the evaluation should be tailored to meet the needs of the individual company and the particular circumstances of that company, board evaluation needs to be a continuous and on-going process rather than a periodic event.

(2) Evaluation should include not only compliance and risk-management competencies, but also skills and experience in business-related and organization-related areas, such as strategy, innovation, marketing, globalization, and growth.

(3) Regulator-issued “best practice” principles and guidelines should provide enough detail to offer genuine help to companies in implementing and evaluation processes, but also leave enough flexibility for companies to tailor the process to their specific needs. Additional guidelines need to provide more information about the criteria, methods, and form of the evaluation process (without compelling companies to make use of them).

(4) The board member or committee responsible for driving the evaluation process should actively involve external experts if, and when, necessary. In addition, “Legal Tech”, specifically board evaluation software and application, can help facilitate the assessment process.

(5) Boards should engage in a more open and detailed form of communication and disclosure about the evaluation process and its outcomes.

Bonne lecture !

Board Evaluation: International Practice

Although there is a broad consensus that we need “better corporate governance,” there is often less agreement as to what this actually means or how we might achieve it. Such uncertainties are hardly surprising. Contemporary corporate governance frameworks were significantly re-worked in the 2000s in response to a series of high-profile scandals. But these reforms appear to have had little effect on the performance of listed companies during the 2008 Financial Crisis. Moreover, the number, scale, and damage of corporate scandals and economic failures do not appear to be diminishing.

One possible reason for the poor performance of corporate governance measures has been an over-emphasis on the regulatory design of “checks-and-balances” in listed companies, rather than on the equally important question of how governance structures can add value to a firm. Our new paper, Evaluating the Board of Directors: International Practice, explores this latter issue, with particular reference to the role of boards and board evaluation.

In the conventional “checks and balances” model of corporate governance, authority and empowerment flow “downwards” from the shareholders (the legal and moral owners of a company) through the board of directors/supervisory board to the management and, eventually, employees. Corporate governance mechanisms are intended to curtail agency problems, notably those that arise between (potentially) self-interested management and investor-owners.

Since management is responsible to the board of directors or supervisory board that, in turn, owes a responsibility to the shareholders or owners of the firm, board members have also been heavily affected by the regulations that have been implemented over the last two decades. In particular, policymakers have emphasized the monitoring and oversight role of “independent” or “outside” directors as crucial in protecting shareholder interests and preventing self-interested transactions. In countries with controlling shareholders, which is common in Europe and Asia, board members are also expected to protect the interests of “minority investors” and other stakeholders in the company. This is deemed necessary because controlling block shareholders may engage in activities that are detrimental to the interests of minority shareholders or other stakeholders in the company.

As such, the dominant view of policymakers has been to treat the board as supervisor/monitors of the senior managers. In consequence, the board of directors has tended to focus on the control of management behavior and the monitoring of company past-performance and sustainability.

An alternative way of framing the issue, however, would be to move beyond a control perspective and recognize that a well-balanced board can be a competitive advantage for a company looking to create value and build its capacity for delivering innovation. Such a broader view can be found in the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, for instance, or, more recently, The New Paradigm, A Roadmap for an Implicit Corporate Governance Partnership Between Corporations and Investors to Achieve Sustainable Long-Term Investment and Growth, issued on 2 September 2016 by the World Economic Forum.

Moreover, companies themselves, as well as their investors, now recognize that the “monitoring” role is no longer sufficient and that the model of board supervision and independence constitutes a missed opportunity. Instead, more innovative firms have integrated a diverse range of individuals onto their boards in the expectation that they will work in collaboration with the firm’s CEO and other senior managers in developing new business strategies. These directors can help a firm stay relevant via the inclusion of diverse perspectives that are directly relevant to a company’s core business operation. A more collaborative model of the relationship between the board and senior management (and the companies’ investors) ensures that these different perspectives are properly integrated into the decision-making processes in a way that can add genuine value to a firm’s business performance.

It is in this context that policymakers, regulators and companies seek to understand better the factors that impact the effectiveness of board performance. As a consequence, board evaluation and evaluation processes have become a key point of interest. In particular, many boards have recognized that it is vital for them to evaluate and assess the effectiveness of their performance on a regular basis. This has resulted in more attention to board evaluations in many jurisdictions. Again, this trend can be seen in the G20/OECD Corporate Governance Principles which recommend including regular board evaluations in a country’s corporate governance framework

As is often the case, however, the risk of regulatory initiatives aimed at forcing or “nudging” changes in corporate behavior is that it merely encourages “box-ticking” in which managing the appearance of compliance becomes the overriding objective. Resources devoted to managing an image of compliance and not substantive compliance are wasted, and the potential gains from meaningful compliance—in this case, effective board evaluation—are never realized.

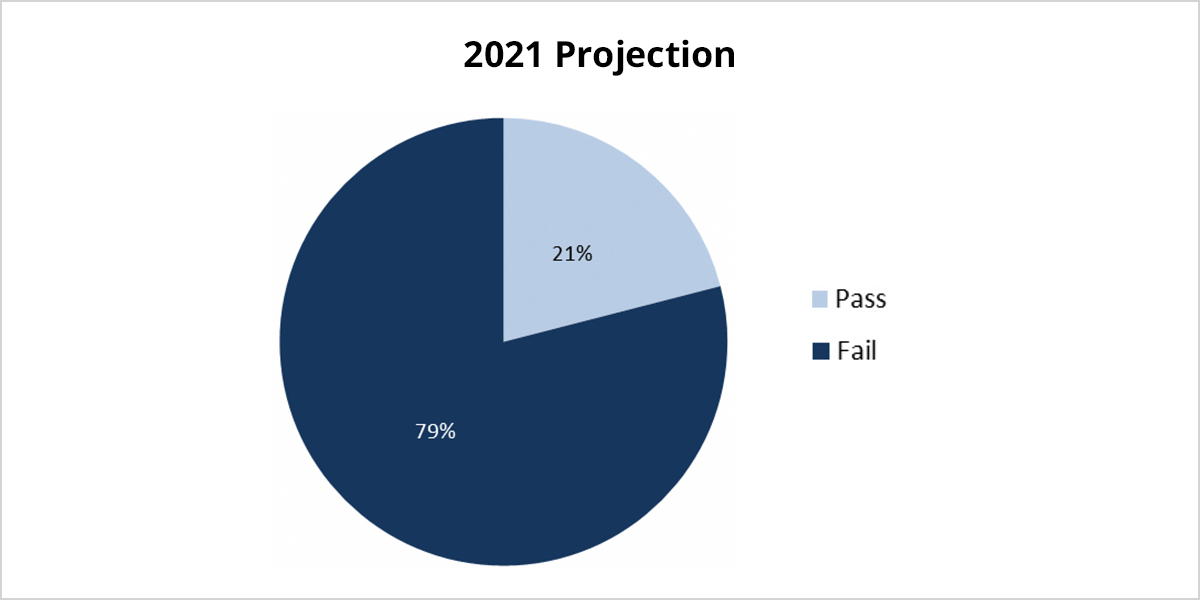

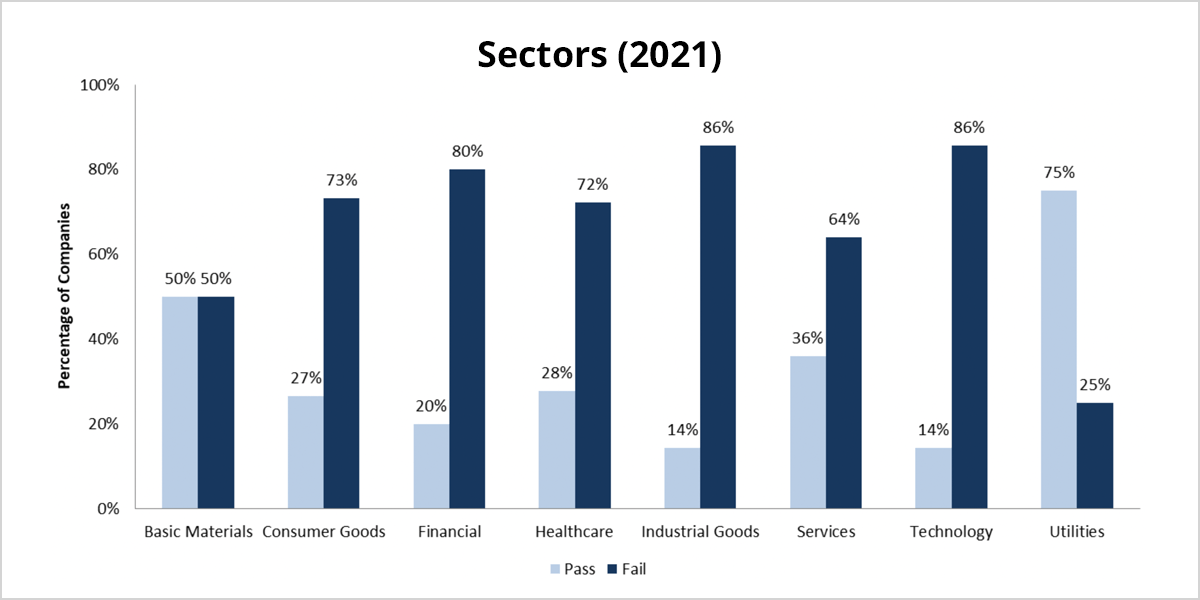

Our paper, therefore, aims to evaluate regulatory measures aimed at promoting meaningful board evaluation. An empirical study of twenty different jurisdictions was conducted employing multiple criteria. The jurisdictions were classified into five groups ranging from no legal provision for board evaluation to jurisdictions with detailed rules and procedures.

The evidence presented in our paper seems to indicate that companies that are listed in countries with more specific principles and rules, as well as substantive guidance on “best practice” do tend to adopt more meaningful and open forms of board evaluation practice than their counterparts in jurisdictions with no or less detailed requirements, i.e., there seems to be evidence that “law matters” in this context.

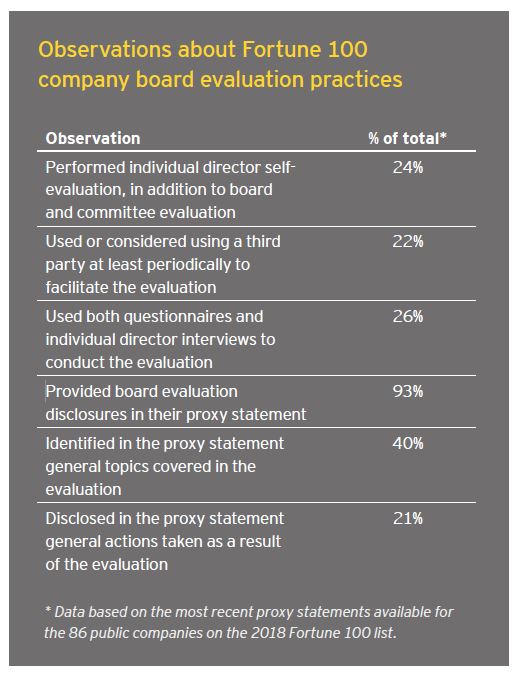

As to what constitutes “best practice” in board evaluation the paper makes a number of findings and suggestions. Crucial amongst them are the suggestions that (1) Although there is “no one-size-fits-all” solution, and the design of the evaluation should be tailored to meet the needs of the individual company and the particular circumstances of that company, board evaluation needs to be a continuous and on-going process rather than a periodic event. (2) Evaluation should include not only compliance and risk-management competencies, but also skills and experience in business-related and organization-related areas, such as strategy, innovation, marketing, globalization, and growth. (3) Regulator-issued “best practice” principles and guidelines should provide enough detail to offer genuine help to companies in implementing and evaluation processes, but also leave enough flexibility for companies to tailor the process to their specific needs. Additional guidelines need to provide more information about the criteria, methods, and form of the evaluation process (without compelling companies to make use of them). (4) The board member or committee responsible for driving the evaluation process should actively involve external experts if—and when—necessary. In addition, “Legal Tech”—specifically board evaluation software and applications—can help facilitate the assessment process. (5) Boards should engage in a more open and detailed form of communication and disclosure about the evaluation process and its outcomes.

“Done right”, board evaluation has the potential to enhance a board’s supervisory functions but—just as importantly—it can allow a firm to identify (and fill) expertise gaps on the board and leverage the expertise of board members to improve firm performance by building strategic partnerships with executives and senior management.

The complete paper is available for download here.

*Mark Fenwick is a Professor at Kyushu University Graduate School of Law and Erik P. M. Vermeulen is Professor of Business & Financial Law at Tilburg University. This post is based on a recent paper by Professor Fenwick and Professor Vermeulen.

Furthermore, the pay can be decent, judging from the NACD and Pearl Meyer & Partners

Furthermore, the pay can be decent, judging from the NACD and Pearl Meyer & Partners