J’ai trouvé très intéressantes les questions qu’un nouvel administrateur pourrait se poser afin de mieux cerner les principaux facteurs liés à la bonne gouvernance d’un conseil d’administration.

Bien sûr, ce petit questionnaire peut également être utilisé par un membre de CA qui veut évaluer la qualité de la gouvernance de son propre conseil d’administration.

Les administrateurs peuvent interroger le président du conseil, les autres membres du conseil et le secrétaire corporatif.

Les douze questions énumérées ci-dessous ont fait l’objet d’une discussion lors d’une table ronde organisée par INSEAD Directors Forum du campus asiatique de Singapore.

Chaque question est accompagnée de quelques réflexions utiles pour permettre le passage à l’acte.

Bonne lecture ! Vos commentaires sont les bienvenus.

In many countries, boards of directors (particularly those of large organisations) have functioned too long as black boxes. Directors’ focus has often—and understandably so—been monopolised by a laundry list of issues to be discussed and typically approved at quarterly meetings.

The board’s own performance, effectiveness, processes and habits receive scant reflection. Many directors are happy to leave the corporate secretary with the task of keeping sight of governance best practices; certainly they do not regard it as their own responsibility.

It occurred to me later that these questions could be of broader use to directors as a framework for beginning a reassessment of their board role.

However, increased regulatory pressures are now pushing boards toward greater responsibility, transparency and self-awareness. In some countries, annual board reviews have become compulsory. In addition, mounting concerns about board diversity provide greater scope for questioning the status quo.

Achieving a more heterogeneous mix of specialisations, cultures and professional experiences entails a willingness to revise some unwritten rules that, in many instances, have governed board functions. And that is not without risk.

At the same time, the “diversity recruits” wooed for board positions may not know the explicit, let alone the implicit, rules. Some doubtless never anticipated they would be asked to join a board. Such invitations often come out of the blue, with little motivation or clarity about what is expected from the new recruit. No universal guidelines are available to aid candidates as they decide whether to accept their invitation.

Long-standing directors and outliers alike could benefit from a crash course in the fundamentals of well-run boards. This was the subject of a roundtable discussion held in February 2017 as part of the INSEAD Directors Forum on the Asia campus.

As discussion leader, I gave the participants, most of whom were recent recipients of INSEAD’s Certificate in Corporate Governance, a basic quiz designed to prompt reflection about how their board applies basic governance principles. It occurred to me later that these questions could be of broader use to directors as a framework for beginning a reassessment of their board role.

Questions and reflections

Q1) True/False: My board maintains a proper ratio of governing vs. executing.

Reflection: Recall basic principles of governance. If you are executing, who is maintaining oversight over you? Why aren’t the executive team executing and the board governing?

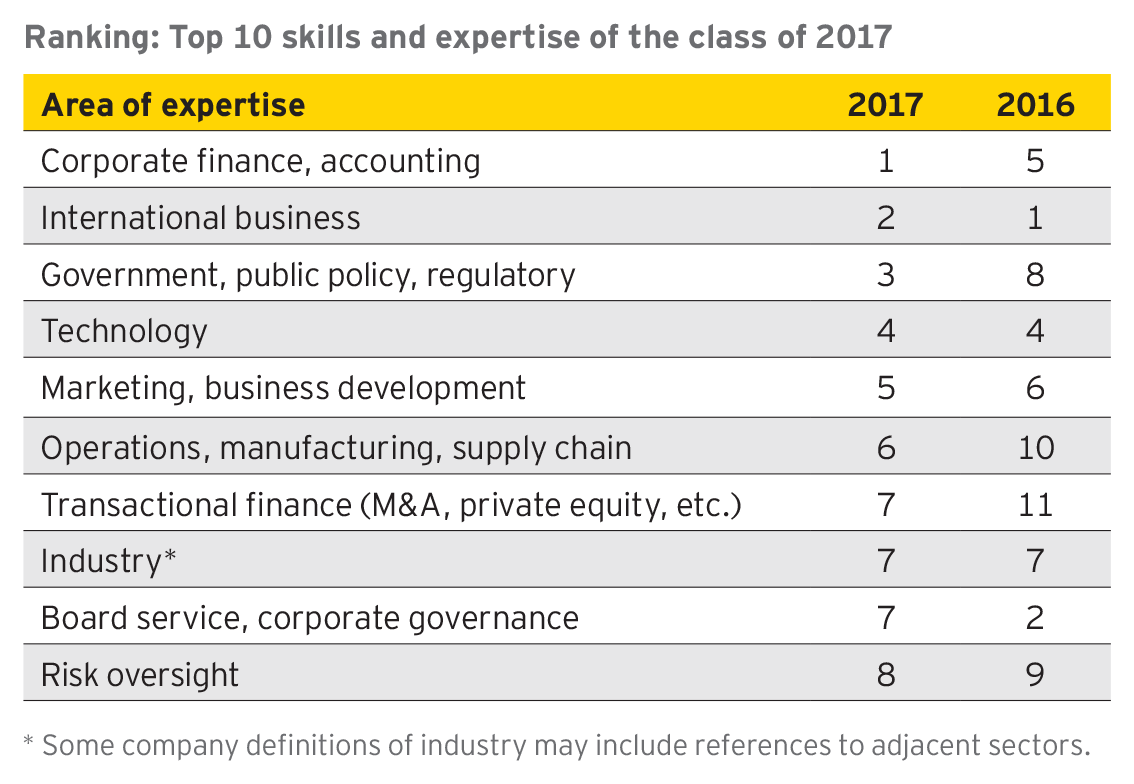

Q2) True/False: My board possesses the required competencies to fulfil its duties.

Reflection: Competencies can be industry-specific or universal (such as being an effective director). Many boards are reluctant to replace members, yet the needs of the organisation shift and demand new competencies, particularly in the digital age. Does your board have a director trained in corporate governance who could take the lead? Or does it adopt the outdated view of governance as a matter for the corporate secretary, perhaps in consultation with owners?

Q3) True/False: The frequency and duration of my board meetings are sufficient.

Reflection: Do you cover what you must cover and have ample time for strategy discussions? Are discussions taking place at the table that should be conducted prior to meetings?

Q4) How frequently does your chairperson meet with management: weekly, fortnightly, monthly, or otherwise?

Reflection: Meetings can be face-to-face or virtual. An alternative question is: Consider email traffic between the chair/board and management—is correspondence at set times (e.g. prior to scheduled meetings/calls) or random in terms of topic and frequency?

Q5) Is this frequency excessive, adequate or insufficient?

Reflection: Consider what is driving the frequency of the meetings (or email traffic). Is there a pressing topic that justifies more frequent interactions? Is there a lack of trust or lack of interest driving the frequency?

Q6) True/False: My board possesses the ideal mix of competencies to handle the most pressing issue on the agenda.

Reflection: If one issue continually appears on the agenda (e.g. marketing-related), there could be reason to review the board’s effectiveness with regards to this issue, and probably the mix of skills within the current board. If the necessary expertise were present at the table, could the board have resolved the issue?

Q7) True/False: The executive team is competent/capable. If “false”, is your board acting on this?

Reflection: At this point in the quiz, you should be considering whether incompetency is the issue. If so, is it being addressed? How comfortable are you, for example, that your executive team is capable of addressing digitisation?

Q8) True/False: My chairperson is effective.

Reflection: Perhaps incompetency rests with the chairperson or with a few board members. Are elements within control of the chairperson well managed? Does your board function professionally? If not, does the chair intervene and improve matters? Are you alone in your views regarding board effectiveness? A “false” answer here should lead you to take an activist role at the table to guide the chair and the board to effectiveness.

Q9) Yes/No: Does your board effectively make use of committees? If “yes”, how many and for which topics? If “no”, why not?

Reflection: Well-defined committees (e.g. audit, nomination, risk) improve the efficiency of board meetings and are a vital component of governance. In the non-profit arena, use of board committees is less common. However, non-profit boards can equally benefit from this basic guiding principle of good governance.

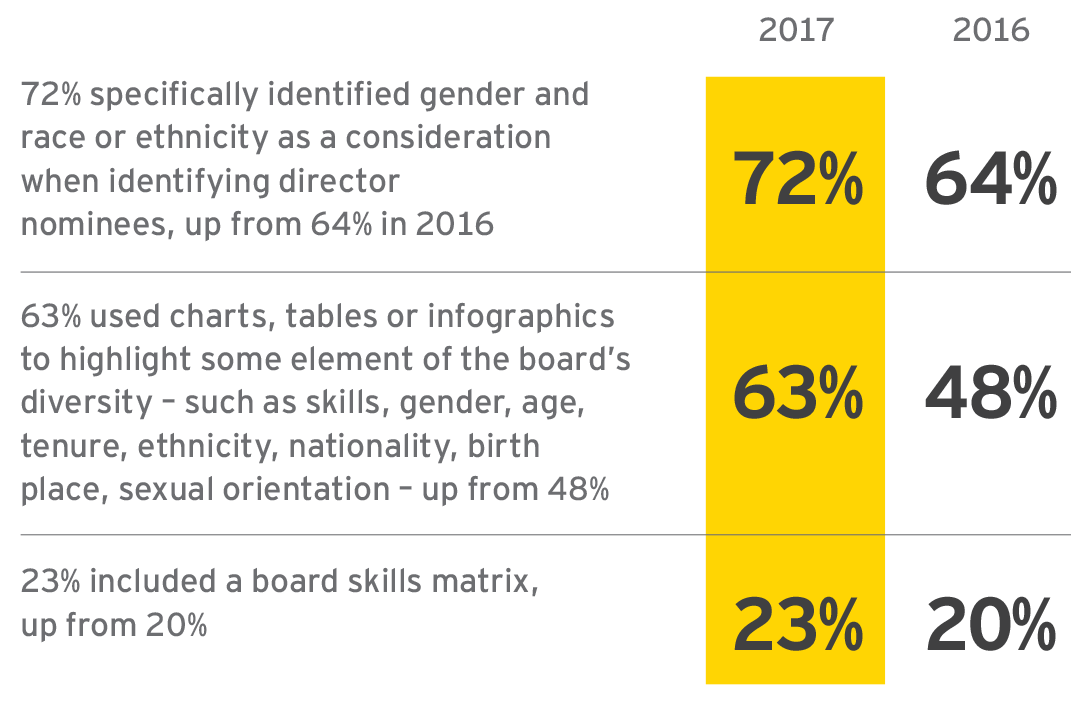

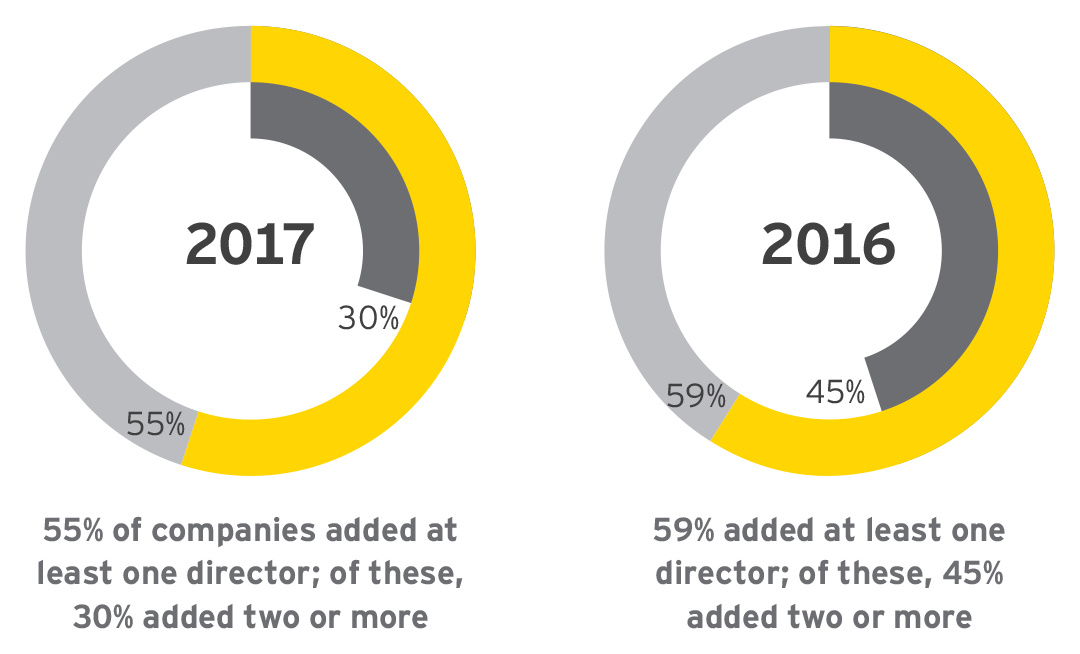

Q10) True/False: Recruitment/nomination of new board members adheres to a robust process.

Reflection: When are openings posted? Who reviews/targets potential candidates? How are candidate criteria determined? And is there a clear “on-boarding” process that is regularly revisited?

Q11) True/False: My board performs a board review annually.

Reflection: A board review will touch on many elements mentioned in previous questions. Obtaining buy-in for the first review might prove painful. Thereafter knowledge of an annual review will undoubtedly lead to more conscious governance and opportunities to introduce improvements (including replacement of board members). Procedurally, the review of the board as a whole should precede the review of individuals.

Q12) Think of a tough decision your board has made. Recall how the decision was reached and results were monitored. Was “fair process leadership” (FPL) at play?

Reflection: Put yourself in the shoes of a fellow board member, perhaps the one most dissatisfied with the outcome of a particular decision. Would that person agree that fair process was adhered to, despite his or her own feelings? Boards that apply fair process move on—as a team—from what is perceived to be a negative outcome for an individual board member. If decisions are made rashly and lack follow-up, FPL is not applied. Energies will quickly leave the room.

From reflection to action

Roundtable participants agreed that these questions should be applied in light of the longevity of the organisation concerned. Compared with most mature organisations, a start-up will need many more board meetings and more interactions between the board and the management team. The “exit” phase of an organisation (or a sub-part of the organisation) is another time in the lifecycle that requires intensified board involvement.

Particularly in the non-profit sector, where directors commonly work pro bono, passion for the organisational mission should be a prerequisite for all prospective board members. However, passion—in the form of a determination to see the organisation’s strategy succeed—should be a consideration for all board members and nominees, regardless of the sector.

Directors who apply the above framework and are dissatisfied with what they discover could seek solutions in their professional networks, corporate governance textbooks or a course such as INSEAD’s International Directors Programme.

If you are considering a board role, you could use the 12 questions, tweak them for your needs and evaluate your answers. Speak not only with the chair, but also with as many board members and relevant executive team members as you can. Understand your comfort level with how the board operates and applies governance principles before accepting a mandate.