Voici un excellent résumé des principales tendances en gouvernance à l’échelle internationale. L’article paru sur le site de la Harvard Law School Forum est le fruit des recherches effectuées par Rusty O’Kelley, membre de CEO and Board Services Practice, et Anthony Goodman, membre de Board Effectiveness Practice de Russell Reynolds Associates.

Les auteurs ont interviewé plusieurs investisseurs activistes et institutionnels ainsi que des administrateurs de sociétés publiques et des experts de la gouvernance afin d’appréhender les tendances qui se dessinent pour les entreprises cotées en 2017.

Parmi les conclusions de l’étude, notons :

- Le besoin de se coller plus étroitement à des normes de gouvernance universellement acceptées ;

- La nécessité de bien se préparer aux nouveaux risques et aux nouvelles opportunités amenées par la montée des gouvernements populistes de droite ;

- Une responsabilité accrue des administrateurs de sociétés pour la création de valeur à long terme ;

- L’importance d’une solide compréhension des changements globaux eu égard à l’exercice d’une bonne gouvernance, notamment dans les états suivants :

– États-Unis

– Union européenne

– Japon

– Inde

– Brésil

Cette lecture nous donne une perspective globale des défis qui attendent les administrateurs et les CA de grandes sociétés publiques en 2017.

Bonne lecture !

Global and Regional Trends in Corporate Governance for 2017

Russell Reynolds Associates recently interviewed numerous institutional and activist investors, pension fund managers, public company directors and other governance professionals about the trends and challenges that public company boards will face in 2017. Our conversations yielded a wide array of perspectives about the forces that are driving change in the corporate governance landscape.

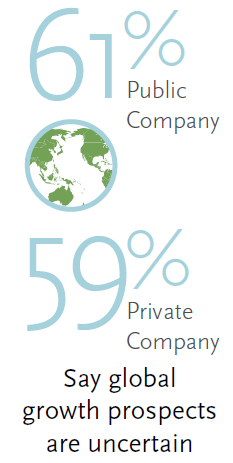

The changing pressures and dynamics that boards will face in the coming year are diverse and significant in their impact. Institutional investors will continue their push for more uniform standards of corporate governance globally, while also increasing their expectations of the role that boards should play in responsibly representing shareholders. Political uncertainty and the surprise results of the US Presidential and “Brexit” votes may require that boards take a more active role in scenario planning and helping management to navigate increasingly costly risks. The movement for companies and investors to adopt a more long-term orientation has gained momentum, with several large institutional investors now pressuring boards to demonstrate that they are actively involved in guiding a company’s strategy for long-term value creation.

Higher Expectations and Greater Alignment Around Corporate Governance Norms

Continuing the trend from last year, large institutional investors and pension funds are pushing for more aligned approaches to corporate governance across borders to support long-term value creation. Regulators are responding, particularly in emerging economies and those with nascent corporate governance regimes. Recent reforms in Japan, India and Brazil have borrowed heavily from the US or UK models. Where regulators have not yet caught up to or agreed with investor expectations, institutional investors are engaging companies directly to advocate for the governance reforms they want to see. These investors also expect more from their boards than ever before and are increasingly willing to intervene when they do not feel they are being responsibly represented in the boardroom.

Corporate Governance in an Era of Political Uncertainty

Populist political movements have gained broad support in several countries around the world, contributing to uncertainty about the future regulatory and political environments of two of the world’s five largest economies. In the UK, the Conservative government has signaled potential support for shareholder influence over executive pay and disclosure of the CEO-employee pay ratio. In the US, President-elect Trump has demonstrated a willingness to “name and shame” specific companies that he perceives to have benefited unfairly from trade deals or moved jobs overseas. Boards must be prepared to navigate these new reputational risks and intense media scrutiny, and review management’s assumptions about the political implications of certain decisions.

Increasing Board Accountability for Long-Term Value Creation

Efforts to encourage a more long-term market orientation have intensified in recent years, with several prominent business leaders and investors, most notably Larry Fink, Chairman and CEO of BlackRock, urging companies to focus on sustained value creation rather than maximizing short-term earnings. In his 2016 letter to chief executives of S&P 500 companies and large European corporations, Mr. Fink specifically called for increased board oversight of a company’s strategy for long-term value creation, noting that BlackRock’s corporate governance team would be looking for assurances of this oversight when engaging with companies.

Global and Regional Trends in Corporate Governance in 2017

Based on our global experience as a firm and our interviews with experts around the world, we believe that public companies will likely face the following trends in 2017:

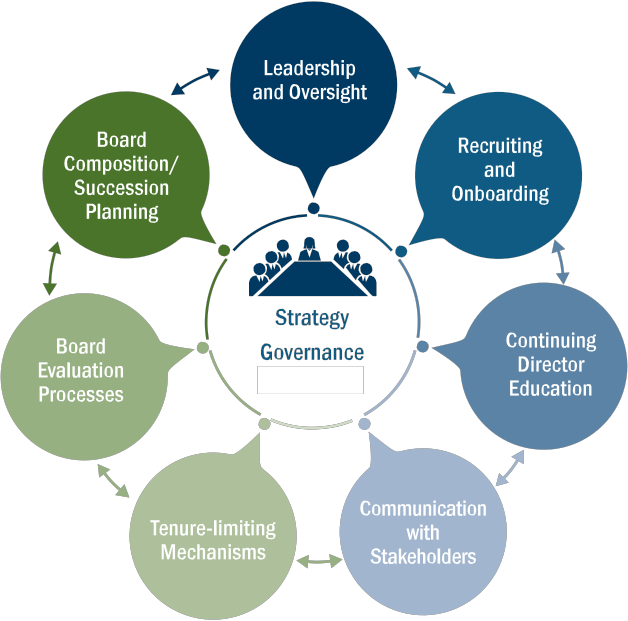

- Increasing expectations around the oversight role of the board, to include greater oversight of strategy and scenario planning, investor engagement, and executive succession planning.

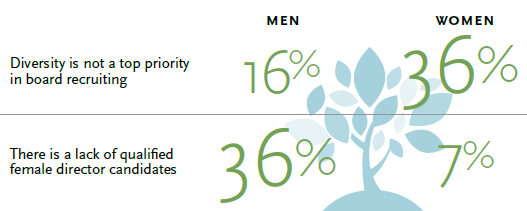

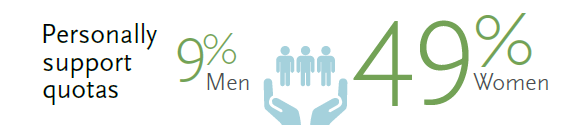

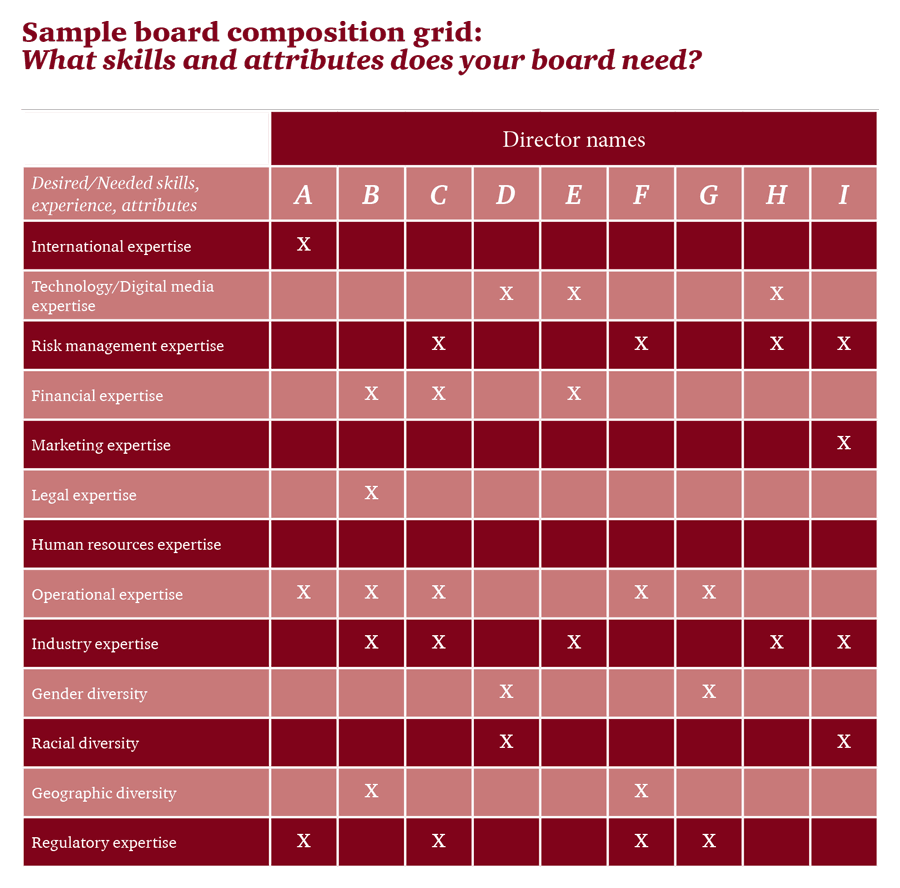

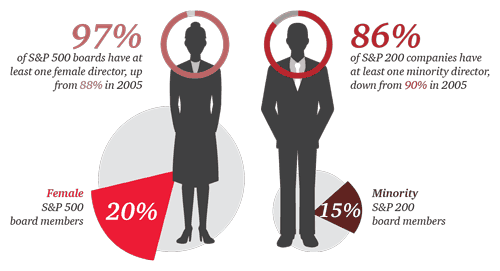

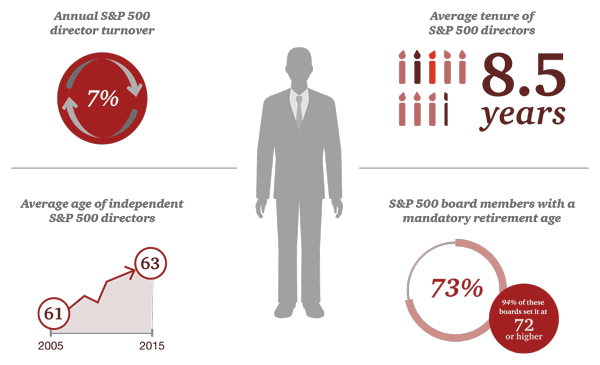

- Continued focus on board refreshment and composition, with particular attention being paid to directors’ skill profiles, the currency of directors’ knowledge, director overboarding, diversity, and robust mechanisms for board refreshment that go beyond box-ticking exercises.

- Greater scrutiny of company plans for sustained value creation, as concerns increase that activist settlements and other market forces are causing short-term priorities to compromise long-term interests.

- Greater focus on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues, and in particular those related to climate change and sustainability, as industries beyond the extractive sector begin to feel investor pressure in this area.

We explore these trends and their implications for five key regions and markets: the United States, the European Union, India, Japan and Brazil.

United States

The surprise election of Donald Trump has increased regulatory and legislative uncertainty. Certain industries, such as financial services, natural resources and healthcare, may face less pressure and government scrutiny. We expect nominees to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to be less supportive of the increased disclosure requirements around executive pay and diversity. However, public pension funds and institutional investors will continue to push governance issues through increased specific engagement with individual companies.

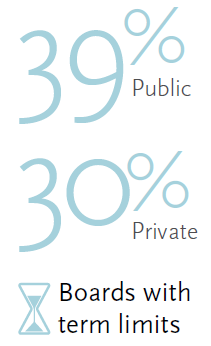

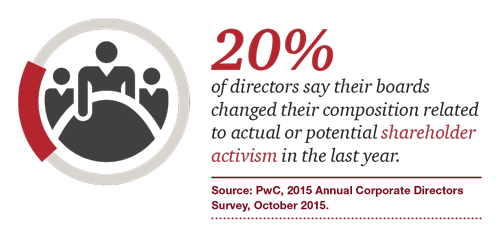

- Investors continue to push boards to demonstrate that they are taking a strategic and proactive approach to board refreshment. In particular, they are looking for indicators that boards are adding directors with the skill sets necessary to complement the company’s strategic direction, and ensuring a diversity of backgrounds and perspectives to guide that strategy. Some investors see tenure and age limits as too blunt an instrument, preferring internal or external board evaluations to ensure that every director is contributing effectively. Several large institutional investors will continue to push boards to conduct external board evaluations by third parties to increase the quality of feedback and improve governance.

- Ongoing fallout from the Wells Fargo scandal will increase pressure on boards to split the CEO/Chair role, particularly in the financial services sector. Given investor pressure, particularly from pension funds, we also anticipate increased demand for clawbacks, a trend that is likely to go beyond the banking sector.

- We expect that 2017 will be a significant year for ESG issues, and in particular those related to climate change and sustainability. Industries beyond the extractive sector will begin to feel investor pressure in this area. While this pressure is being exerted by a number of stakeholder groups, the degree to which the baton has been picked up by mainstream institutional investors is notable.

- Increased attention on climate risk is also changing the way many companies and investors think about materiality and disclosure, which will have significant implications for audit committees. Michael Bloomberg is currently leading the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, which will seek to develop consistent, voluntary standards for companies to provide information about climate-related financial risk. The Task Force’s recommendations are expected in mid-2017.

- Boards will increasingly be expected to ensure sufficient succession planning not just at the CEO level but in other key C-suite roles as well, as investors want to know that boards are actively monitoring the pipeline of talent. Additionally, there is a relatively new trend of some boards conducting crisis management exercises as a supplement to the activism risk assessment we have seen over the past couple of years.

- In the event that all or parts of the Dodd-Frank regulations are repealed, investors will likely turn to private ordering—seeking to persuade companies to change their by-laws—to keep the elements that are most important to them (e.g. “say on pay”). Current SEC rules require that companies begin disclosing their CEO-employee pay ratio in 2018, but we believe this to be a likely target for repeal.

European Union

Across many countries in Europe, the push for board and management diversity will continue apace in 2017. Executive pay continues to be the focus of government, investor and media attention with various proposals for reining in compensation. Work being done in the UK on board oversight of corporate culture has the potential to spill across European borders and travel farther afield over the next few years.

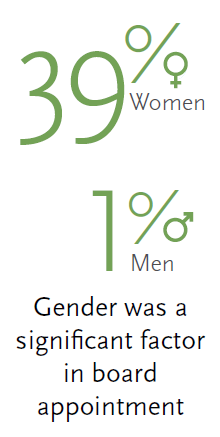

- Many countries in Europe continue to push ahead with encouraging gender diversity at the board level, as national laws regulating the number of female directors proliferate. In the UK, the Hampton-Alexander Review recommended that the Corporate Governance Code be amended to require FTSE 350 companies to disclose the gender balance of their executive committees in their annual report.

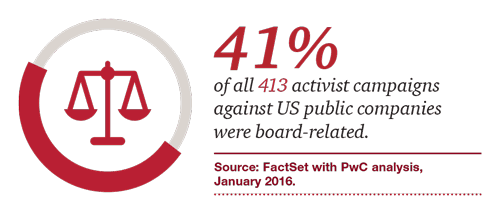

- After ebbing slightly in 2014, activism has made a comeback in Europe: whereas 51 companies were targeted in 2014, 64 were targeted in the first half of 2016 alone. We anticipate that European activists will continue to apply less aggressive and more collaborative tactics than those seen in the US. Additionally, we expect to see US and European institutional investors to be supportive of European activist investors, particularly those who are self-described “constructive activists”, who take a less aggressive approach than their US counterparts.

- The EU is expected to amend its Shareholder Rights Directive in 2017 to include an EU-wide “say on pay” framework that would give shareholders the right to regular votes on prospective and retrospective remuneration. While these votes are not expected to be binding, the directive does require that pay be based on a shareholder-approved policy and that issuers must address failed votes. Germany saw a sharp increase in dissents on “say on pay” proposals this year, jumping from 8% to over 20%. In France, the government is currently debating whether to make “say on pay” votes binding, spurred by the public outcry about the Renault board’s decision to confirm the CEO’s 2015 compensation, despite a rejection by a majority of shareholders.

- The UK government is expected to continue its push for compensation practice reform in 2017, having recently published a series of proposed policies, including mandatory disclosure of the CEO pay ratio, employee representation in executive compensation decisions, and making shareholder votes on executive compensation binding. We also expect continued strong media coverage and related public opposition to large public company pay packages, which could put UK boards in the spotlight.

- In Germany, the ongoing fallout from the Volkswagen scandal is the likely impetus for proposed amendments to the corporate governance code that would underscore boards’ obligations to adhere to ethical business practices. The proposed amendments also acknowledge the increasingly common practice of investor engagement with the supervisory board, and recommend that the supervisory board chair be prepared to discuss relevant topics with investors.

- In the UK, boards will be focused on implementing the recommendations of the recent Financial Reporting Council (FRC) report on corporate culture and the role of boards, which makes the case that long-term value creation is directly linked to company culture and the role of business in society.

India

Indian boards continue to struggle with the implementation of many of the major changes to corporate governance practices required by the 2013 Companies Act, but reform is progressing. While the complete fallout from the recent Tata leadership imbroglio is not yet clear, it will almost certainly reverberate through the Indian corporate governance landscape for years to come.

- Recent regulatory changes have increased the scope of responsibilities for the Nomination and Remuneration Committee, requiring boards to ensure that directors have the right set of skills to deliver on these new responsibilities. Increased emphasis on CEO succession planning and board evaluations have necessitated that Committee members become more fluent in these governance processes and methodologies, particularly as the requirement to report on them annually has increased the spotlight on the board’s role in these processes.

- The introduction in 2013 of a mandatory minimum of at least one female director for most listed companies has increased India’s gender diversity at the board level to one of the highest rates in Asia, with 14% of all directorships currently held by women. However, concerns persist about the potential for “tokenism”, as a sizeable portion of the women appointed come from the controlling families of the company.

- India has also attempted to integrate ESG and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) issues at the board level, having mandated that every board establish a CSR committee and that the company spend 2% of net profits on CSR activities. However, companies will need to ensure that their approach to CSR amounts to more than a box-ticking exercise if they want to attract the support of the growing cadre of ESG-focused investors.

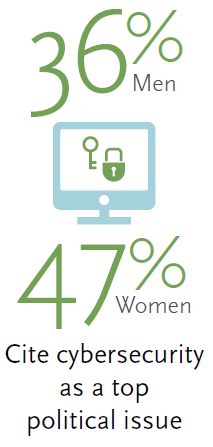

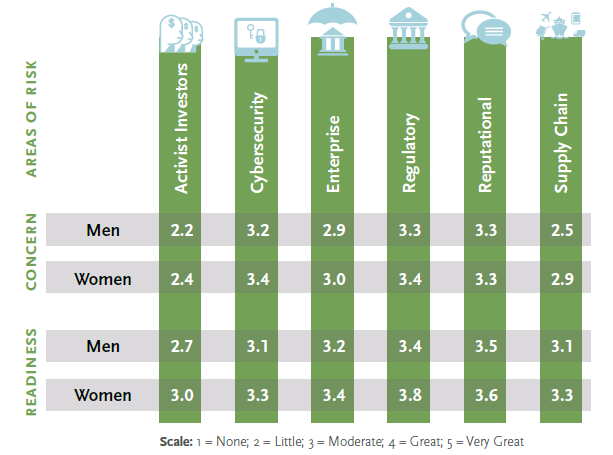

- Boards are increasingly expected to take a more active role in risk management, particularly cybersecurity risks. Boards should also ensure that their companies are adequately anticipating and responding to cybersecurity threats.

- Changes to the 2013 Companies Act have considerably enhanced the duties and liabilities of directors, along with strict penalties for any breach of these duties and the potential for class action lawsuits against individual directors. While potentially helpful in increasing director accountability, these changes also significantly increase the personal risk that a director assumes when joining a board.

Japan

Japan’s Corporate Governance Code was reformulated in 2015, as part of the “Abenomics” push for structural reforms. Japanese companies continue to implement the corporate governance principles resulting from the new regulations, with many hoping that the adoption of more Western norms will help prompt the return of foreign investors.

- The overhaul of Japan’s corporate governance model in 2015 has begun to yield significant results, as 96% of Japanese boards now have at least one outside director and 78% have at least two. However, Japan’s famously deferential corporate culture may make it difficult for boards to unlock the value of these independent perspectives, as seniority and family ownership often still take precedence.

- Increasing investor interest in the Japanese market is likely to increase pressure on boards to adopt more Western norms of corporate governance. CalPERS, the California public pension fund, recently began an explicit program of engagement in Japan, their second-largest equity market, in order to encourage the adoption of more Western norms, including increased board independence and diversity, defining narrower standards of independence, and increasing the disclosure of director qualifications.

- Gender diversity remains a challenge for Japanese boards, with only 3% of directorships held by women. However, women account for 22% of outside directors, suggesting that gender diversity on boards will likely continue to increase as the appointment of independent directors becomes more common. A new law, introduced in April 2016, now requires companies with more than 300 employees to publish data on the number of women they employ and how many hold management positions. We anticipate this increased scrutiny at all levels of the company to have a knock-on effect for boards.

- While other elements of the new Corporate Governance Code have seen near unanimous compliance, only 55% of listed companies have complied with the stipulation to conduct formal board evaluations. Moreover, the quality and format of the evaluations that are occurring vary significantly, with many adopting a self-evaluation process that amounts to little more than a box-ticking exercise.

- The common Japanese practice of former executives and chairs remaining in “advisor” roles beyond the end of their formal tenure is now coming under increasing scrutiny. ISS will now generally vote against amendments to create new advisory positions, unless the advisors will serve on the board and therefore be held accountable to shareholders.

Brazil

Brazil’s corporate governance regime has evolved significantly in the last decade, as various regulatory entities have sought to apply greater protections for minority shareholders and better align standards with other Western models to attract greater foreign investment.

- As Brazil continues to navigate the fallout of the Petrobras scandal, many are questioning how the mechanisms for encouraging and enforcing investor stewardship and corporate governance can be strengthened.

- AMEC, Brazil’s association of institutional investors, recently released the country’s first Investor Stewardship Code, calling on investors to adhere to seven principles, including implementing mechanisms to manage conflicts of interest, taking ESG issues into account, and being active and diligent in the exercise of voting rights.

- In an effort to address the high levels of absenteeism among institutional investors at general meetings, Brazil’s Security and Exchange Commission (CVM) will, beginning in 2017, require that listed companies allow shareholders to vote by mail or email, rather than requiring that they (or their proxy) be physically present to cast their vote. Brazilian companies, and their boards, should be prepared for the increased requests for investor engagement that are likely to result from the more active participation of institutional investors in the voting process.

- New regulations for the country’s Novo Mercado segment of listed companies will be announced in 2017. Highlights of the proposed changes include the required establishment of audit, compensation and appointment committees, a minimum of two independent directors, and more stringent disclosure of directors’ relationships to related companies and other parties.