Je suis tout à fait d’accord avec la teneur de l’article de l’IGOPP, publié par Yvan Allaire* intitulé « Six mesures pour améliorer la gouvernance des organismes publics au Québec », lequel dresse un état des lieux qui soulève des défis considérables pour l’amélioration de la gouvernance dans le secteur public et propose des mesures qui pourraient s’avérer utiles. Celui-ci fut a été soumis au journal Le Devoir, pour publication.

L’article soulève plusieurs arguments pour des conseils d’administration responsables, compétents, légitimes et crédibles aux yeux des ministres responsables.

Même si la Loi sur la gouvernance des sociétés d’État a mis en place certaines dispositions qui balisent adéquatement les responsabilités des C.A., celles-ci sont poreuses et n’accordent pas l’autonomie nécessaire au conseil d’administration, et à son président, pour effectuer une véritable veille sur la gestion de ces organismes.

Selon l’auteur, les ministres contournent allègrement les C.A., et ne les consultent pas. La réalité politique amène les ministres responsables à ne prendre principalement avis que du PDG ou du président du conseil : deux postes qui sont sous le contrôle et l’influence du ministère du conseil exécutif ainsi que des ministres responsables des sociétés d’État (qui ont trop souvent des mandats écourtés !).

Rappelons, en toile de fond à l’article, certaines dispositions de la loi :

– Au moins les deux tiers des membres du conseil d’administration, dont le président, doivent, de l’avis du gouvernement, se qualifier comme administrateurs indépendants.

– Le mandat des membres du conseil d’administration peut être renouvelé deux fois

– Le conseil d’administration doit constituer les comités suivants, lesquels ne doivent être composés que de membres indépendants :

1 ° un comité de gouvernance et d’éthique ;

2 ° un comité d’audit ;

3 ° un comité des ressources humaines.

– Les fonctions de président du conseil d’administration et de président-directeur général de la société ne peuvent être cumulées.

– Le ministre peut donner des directives sur l’orientation et les objectifs généraux qu’une société doit poursuivre.

– Les conseils d’administration doivent, pour l’ensemble des sociétés, être constitués à parts égales de femmes et d’hommes.

Yvan a accepté d’agir en tant qu’auteur invité dans mon blogue en gouvernance. Voici donc son article.

Six mesures pour améliorer la gouvernance des organismes publics au Québec

par Yvan Allaire*

La récente controverse à propos de la Société immobilière du Québec a fait constater derechef que, malgré des progrès certains, les espoirs investis dans une meilleure gouvernance des organismes publics se sont dissipés graduellement. Ce n’est pas tellement les crises récurrentes survenant dans des organismes ou sociétés d’État qui font problème. Ces phénomènes sont inévitables même avec une gouvernance exemplaire comme cela fut démontré à maintes reprises dans les sociétés cotées en Bourse. Non, ce qui est remarquable, c’est l’acceptation des limites inhérentes à la gouvernance dans le secteur public selon le modèle actuel.

En fait, propriété de l’État, les organismes publics ne jouissent pas de l’autonomie qui permettrait à leur conseil d’administration d’assumer les responsabilités essentielles qui incombent à un conseil d’administration normal : la nomination du PDG par le conseil (sauf pour la Caisse de dépôt et placement, et même pour celle-ci, la nomination du PDG par le conseil est assujettie au veto du gouvernement), l’établissement de la rémunération des dirigeants par le conseil, l’élection des membres du conseil par les « actionnaires » sur proposition du conseil, le conseil comme interlocuteur auprès des actionnaires.

Ainsi, le C.A. d’un organisme public, dépouillé des responsabilités qui donnent à un conseil sa légitimité auprès de la direction, entouré d’un appareil gouvernemental en communication constante avec le PDG, ne peut que difficilement affirmer son autorité sur la direction et décider vraiment des orientations stratégiques de l’organisme.

Pourtant, l’engouement pour la « bonne » gouvernance, inspirée par les pratiques de gouvernance mises en place dans les sociétés ouvertes cotées en Bourse, s’était vite propagé dans le secteur public. Dans un cas comme dans l’autre, la notion d’indépendance des membres du conseil a pris un caractère mythique, un véritable sine qua non de la « bonne » gouvernance. Or, à l’épreuve, on a vite constaté que l’indépendance qui compte est celle de l’esprit, ce qui ne se mesure pas, et que l’indépendance qui se mesure est sans grand intérêt et peut, en fait, s’accompagner d’une dangereuse ignorance des particularités de l’organisme à gouverner.

Ce constat des limites des conseils d’administration que font les ministres et les ministères devrait les inciter à modifier ce modèle de gouvernance, à procéder à une sélection plus serrée des membres de conseil, à prévoir une formation plus poussée des membres de C.A. sur les aspects substantifs de l’organisme dont ils doivent assumer la gouvernance.

Or, l’État manifeste plutôt une indifférence courtoise, parfois une certaine hostilité, envers les conseils et leurs membres que l’on estime ignorants des vrais enjeux et superflus pour les décisions importantes.

Évidemment, le caractère politique de ces organismes exacerbe ces tendances. Dès qu’un organisme quelconque de l’État met le gouvernement dans l’embarras pour quelque faute ou erreur, les partis d’opposition sautent sur l’occasion, et les médias aidant, le gouvernement est pressé d’agir pour que le « scandale » s’estompe, que la « crise » soit réglée au plus vite. Alors, les ministres concernés deviennent préoccupés surtout de leur contrôle sur ce qui se fait dans tous les organismes sous leur responsabilité, même si cela est au détriment d’une saine gouvernance.

Ce brutal constat fait que le gouvernement, les ministères et ministres responsables contournent les conseils d’administration, les consultent rarement, semblent considérer cette agitation de gouvernance comme une obligation juridique, un mécanisme pro-forma utile qu’en cas de blâme à partager.

Prenant en compte ces réalités qui leur semblent incontournables, les membres des conseils d’organismes publics, bénévoles pour la plupart, se concentrent alors sur les enjeux pour lesquels ils exercent encore une certaine influence, se réjouissent d’avoir cette occasion d’apprentissage et apprécient la notoriété que leur apporte dans leur milieu ce rôle d’administrateur.

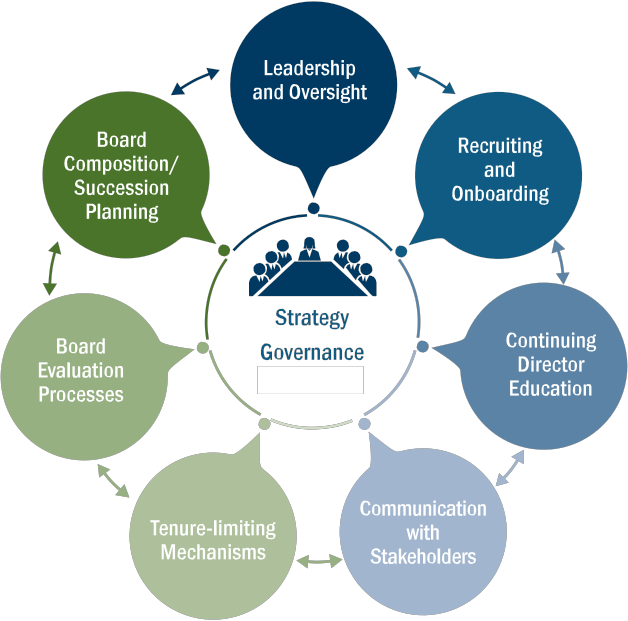

Cet état des lieux, s’il est justement décrit, soulève des défis considérables pour l’amélioration de la gouvernance dans le secteur public. Les mesures suivantes pourraient s’avérer utiles :

- Relever considérablement la formation donnée aux membres de conseil en ce qui concerne les particularités de fonctionnement de l’organisme, ses enjeux, ses défis et critères de succès. Cette formation doit aller bien au-delà des cours en gouvernance qui sont devenus quasi-obligatoires. Sans une formation sur la substance de l’organisme, un nouveau membre de conseil devient une sorte de touriste pendant un temps assez long avant de comprendre suffisamment le caractère de l’organisation et son fonctionnement.

- Accorder aux conseils d’administration un rôle élargi pour la nomination du PDG de l’organisme ; par exemple, le conseil pourrait, après recherche de candidatures et évaluation de celles-ci, recommander au gouvernement deux candidats pour le choix éventuel du gouvernement. Le conseil serait également autorisé à démettre un PDG de ses fonctions, après consultation du gouvernement.

- De même, le gouvernement devrait élargir le bassin de candidats et candidates pour les conseils d’administration, recevoir l’avis du conseil sur le profil recherché.

- Une rémunération adéquate devrait être versée aux membres de conseil ; le bénévolat en ce domaine prive souvent les organismes de l’État du talent essentiel au succès de la gouvernance.

- Rendre publique la grille de compétences pour les membres du conseil dont doivent se doter la plupart des organismes publics ; fournir une information détaillée sur l’expérience des membres du conseil et rapprocher l’expérience/expertise de chacun de la grille de compétences établie. Cette information devrait apparaître sur le site Web de l’organisme.

- Au risque de trahir une incorrigible naïveté, je crois que l’on pourrait en arriver à ce que les problèmes qui surgissent inévitablement dans l’un ou l’autre organisme public soient pris en charge par le conseil d’administration et la direction de l’organisme. En d’autres mots, en réponse aux questions des partis d’opposition et des médias, le ministre responsable indique que le président du conseil de l’organisme en cause et son PDG tiendront incessamment une conférence de presse pour expliquer la situation et présenter les mesures prises pour la corriger. Si leur intervention semble insuffisante, alors le ministre prend en main le dossier et en répond devant l’opinion publique.

_______________________________________________

*Yvan Allaire, Ph. D. (MIT), MSRC Président exécutif du conseil, IGOPP Professeur émérite de stratégie, UQÀM