La considération de l’éthique et des valeurs d’intégrité sont des sujets de grande actualité dans toutes les sphères de la vie organisationnelle*. À ce propos, le Réseau d’éthique organisationnelle du Québec (RÉOQ) tient son colloque annuel les 25 et 26 octobre 2018 à l’hôtel Marriott Courtyard Montréal Centre-Ville et il propose plusieurs conférences qui traitent de l’éthique au quotidien. Je vous invite à consulter le programme du colloque et y participer.

Ne vous méprenez pas, la saine gouvernance des entreprises repose sur l’attention assidue accordée aux questions éthiques par le président du conseil, par le comité de gouvernance et d’éthique, ainsi que par tous les membres du conseil d’administration. Ceux-ci ont un devoir inéluctable de respect de la charte éthique approuvée par le CA.

Les défaillances en ce qui a trait à l’intégrité des personnes et les manquements de nature éthique sont souvent le résultat d’un conseil d’administration qui n’exerce pas un fort leadership éthique et qui n’affiche pas de valeurs transparentes à ce propos. Ainsi, il faut affirmer haut et fort que les comportements des employés sont largement tributaires de la culture de l’entreprise, des pratiques en cours, des contrôles internes… Et que les administrateurs sont les fiduciaires de ces valeurs qui font la réputation de l’entreprise !

Cette affirmation implique que tous les membres d’un conseil d’administration doivent faire preuve de comportements éthiques exemplaires : « Tone at the Top ». Les administrateurs doivent se donner les moyens d’évaluer cette valeur au sein de leur conseil, et au sein de l’organisation.

C’est la responsabilité du conseil de veiller à ce que de solides valeurs d’intégrité soient transmises à l’échelle de toute l’organisation, que la direction et les employés connaissent bien les codes de conduites et que l’on s’assure d’un suivi adéquat à cet égard.

Mais là où les CA achoppent trop souvent dans l’établissement d’une solide conduite éthique, c’est (1) dans la formulation de politiques probantes (2) dans la mise en place de l’instrumentalisation requise (3) dans le recrutement de personnes qui adhèrent aux objectifs énoncés et (4) dans l’évaluation et le suivi du climat organisationnel.

Les administrateurs doivent poser les bonnes questions sur la situation existante et prendre le recul nécessaire pour envisager les divers points de vue des parties prenantes dans le but d’assurer la transmission efficace du code de conduite de l’entreprise.

Les préconceptions et les préjugés sont coriaces, mais ils doivent être confrontés lors des échanges de vues au CA ou lors des huis clos. Les administrateurs doivent aborder les situations avec un esprit ouvert et indépendant.

Vous aurez compris que le président du conseil a un rôle clé à cet égard. C’est lui qui doit incarner le leadership en matière d’éthique et de culture organisationnelle. L’une de ses tâches est de s’assurer qu’il consacre le temps approprié aux questionnements éthiques. Pour ce faire, le président du CA doit poser des gestes concrets (1) en plaçant les considérations éthiques à l’ordre du jour (2) en s’assurant de la formation des administrateurs (3) en renforçant le rôle du comité de gouvernance et (4) en mettant le comportement éthique au cœur de ses préoccupations.

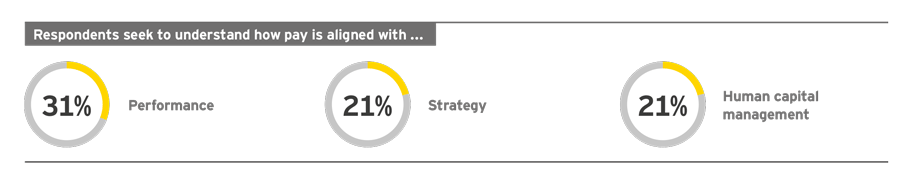

Le choix du premier dirigeant (PDG) est l’une des plus grandes responsabilités des conseils d’administration. Lors du processus de sélection, on doit s’assurer que le PDG incarne les valeurs éthiques qui correspondent aux attentes élevées des administrateurs ainsi qu’aux pratiques en vigueur. L’évaluation annuelle des dirigeants doit tenir compte de leur engagement éthique, et le résultat doit se refléter dans la rémunération variable des dirigeants.

Quels items peut-on utiliser pour évaluer la composante éthique de la gouvernance du conseil d’administration ? Voici un instrument qui peut aider à y voir plus clair. Ce cadre de référence novateur a été conçu par le Bureau de vérification interne de l’Université de Montréal.

| 1. Les politiques de votre organisation visant à favoriser l’éthique sont-elles bien connues et appliquées par ses employés, partenaires et bénévoles ? |

| 2. Le Conseil de votre organisation aborde-t-il régulièrement la question de l’éthique, notamment en recevant des rapports sur les plaintes, les dénonciations ? |

| 3. Le Conseil et l’équipe de direction de votre organisation participent-ils régulièrement à des activités de formation visant à parfaire leurs connaissances et leurs compétences en matière d’éthique ? |

| 4. S’assure-t-on que la direction générale est exemplaire et a développé une culture fondée sur des valeurs qui se déclinent dans l’ensemble de l’organisation ? |

| 5. S’assure-t-on que la direction prend au sérieux les manquements à l’éthique et les gère promptement et de façon cohérente ? |

| 6. S’assure-t-on que la direction a élaboré un code de conduite efficace auquel elle adhère, et veille à ce que tous les membres du personnel en comprennent la teneur, la pertinence et l’importance ? |

| 7. S’assure-t-on de l’existence de canaux de communication efficaces (ligne d’alerte téléphonique dédiée, assistance téléphonique, etc.) pour permettre aux membres du personnel et partenaires de signaler les problèmes ? |

| 8. Le Conseil reconnaît-il l’impact sur la réputation de l’organisation du comportement de ses principaux fournisseurs et autres partenaires ? |

| 9. Est-ce que le président du Conseil donne le ton au même titre que le DG au niveau des opérations sur la culture organisationnelle au nom de ses croyances, son attitude et ses valeurs ? |

|

10. Est-ce que l’organisation a la capacité d’intégrer des changements à même ses processus, outils ou comportements dans un délai raisonnable ? |

*Autres lectures pertinentes :

- Formation en éthique 2.0 pour les conseils d’administration

- Rapport spécial sur l’importance de l’éthique dans l’amélioration de la gouvernance | Knowledge@Wharton

- Rôle du conseil d’administration en matière d’éthique*

- Comment le CA peut-il exercer une veille de l’éthique ?

- Le CA est garant de l’intégrité de l’entreprise

- Cadre de référence pour évaluer la gouvernance des sociétés | Questionnaire de 100 items