Investors, regulators and other stakeholders are seeking greater board effectiveness and accountability and are increasingly interested in board evaluation processes and results. Boards are also seeking to enhance their own effectiveness and to more clearly address stakeholder interest by enhancing their board evaluation processes and disclosures.

The focus on board effectiveness and evaluation reflects factors that have shaped public company governance in recent years, including:

Recent high-profile examples of board oversight failures

Increased complexity, uncertainty, opportunity and risk in business environments globally

Pressure from stakeholders for companies to better explain and achieve current and long-term corporate performance

Board evaluation requirements outside the US, in particular the UK

Increased focus on board composition by institutional investors

Activist investors

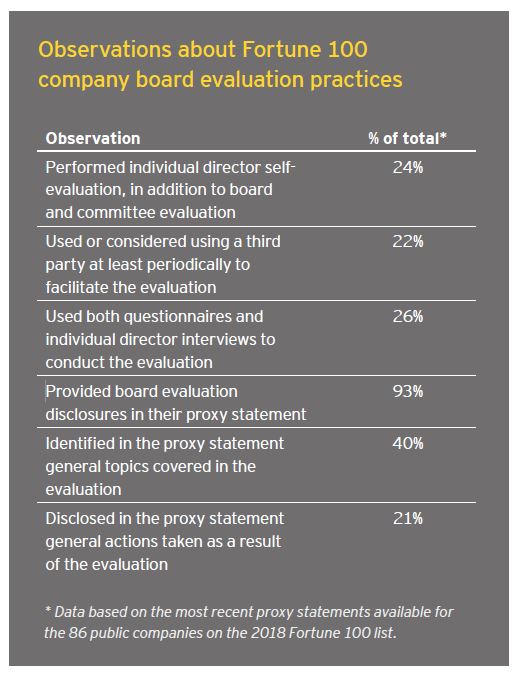

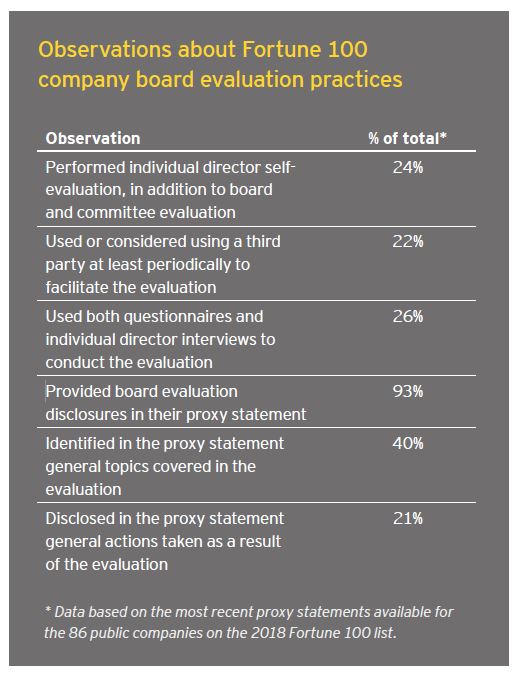

In view of these developments, we reviewed the most recent proxy statements filed by companies in the 2018 Fortune 100 to identify notable board evaluation practices, trends and disclosures. Our first observation is that 93% of proxy filers in the Fortune 100 provided at least some disclosures about their board evaluation process. This publication outlines elements that can be considered in designing an effective evaluation process and notes related observations from our proxy statement review.

Planning and designing an effective evaluation process

Prior to designing and implementing an evaluation process, boards should determine the substantive and specific goals and objectives they want to achieve through evaluation.

The evaluation process should not be used simply as a way to assess whether the board, its committees and its members have satisfactorily performed their required duties and responsibilities. Instead, the evaluation process should be designed to rigorously test whether the board’s composition, dynamics, operations and structure are effective for the company and its business environment, both in the short- and long-term, by:

Focusing director introspection on actual board, committee and director performance compared to agreed-upon board, committee and director performance goals, objectives and requirements

Eliciting valuable and candid feedback from each board member, without attribution if appropriate, about board dynamics, operations, structure, performance and composition

Reaching board agreement on action items and corresponding timelines to address issues observed in the evaluation process

Holding the board accountable for regularly reviewing the implementation of evaluation-related action items, measuring results against agreed-upon goals and expectations, and adjusting actions in real-time to meet evaluation goals and objectives

In determining the most effective approach to evaluation, boards should determine who should lead the evaluation process, who and what should be evaluated, and how and when the evaluation process should be conducted and communicated.

Leading the evaluation process

Leadership is key in designing and implementing an effective evaluation process that will objectively elicit valuable and candid director feedback about board dynamics, operations, structure, performance and composition.

A majority (69%) of Fortune 100 proxy filers disclosed that their corporate governance and nominating committee performed the evaluation process either alone or together with the lead independent director or chair. These companies also disclosed that evaluation leaders did or could involve others in the evaluation process, including third parties, internal advisors and external legal counsel. Twenty-two percent of Fortune 100 proxy filers disclosed using or considering the use of an independent third party to facilitate the evaluation at least periodically.

Determining who to evaluate

Board and committee evaluations have long been required of all public companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Today, board and committee evaluations are best practice for all public companies.

Approximately one-quarter (24%) of Fortune 100 proxy filers disclosed that they included individual director self-evaluation along with board and committee evaluation. Ten percent of Fortune 100 proxy filers disclosed that they conducted peer evaluations. Individual director self and peer evaluations are discussed below.

Prioritizing evaluation topics

Board, committee and individual director evaluation topics should be customized and prioritized to elicit valuable, candid and useful feedback on board dynamics, operations, structure, performance and composition. Relevant evaluation topics and areas of focus should be drawn from:

Analysis of board and committee minutes and meeting materials

Board governance documents, such as corporate governance guidelines, committee charters, director qualification standards, as well as company codes of conduct and ethics

Observations relevant to board dynamics, operations, structure, performance and composition

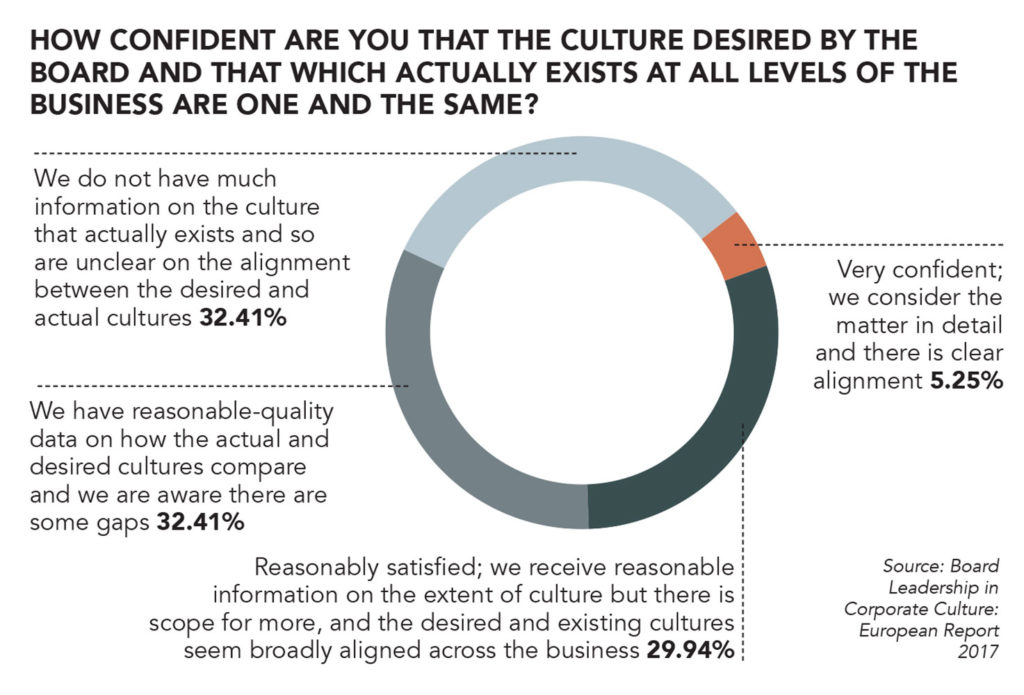

Company culture, performance, business environment conditions and strategy

Investor and stakeholder engagement on board composition, performance and oversight

Forty percent of Fortune 100 proxy filers disclosed the general topics covered by the evaluation. These disclosures typically focus on core board duties and responsibilities and oversight functions, such as:

Strategy, risk and financial performance

Board composition and structure

Company integrity, reputation and culture

Management performance and succession planning

Asking focused evaluation questions to elicit valuable feedback

About 40% of Fortune 100 proxy filers disclosed use of questionnaires in their evaluation process, with 15% disclosing use of only questionnaires and 25% disclosing use of both questionnaires and interviews. Questionnaires are a key tool in the evaluation process, but must be thoughtfully and carefully drafted to be effective. Questionnaire responses can be provided without attribution, which can promote candid and more detailed feedback.

Questionnaires are helpful because each director receives the same question set—even if there are separate questionnaires for the board, its committees and individual directors. This approach facilitates comparison of director responses and can help indicate the magnitude of any actual or potential issues as well as variances in director perspective and perception.

Evaluation questionnaires often put questions in the form of a statement, such as “The board is the right size,” which calls for a response along a numerical scale. The larger the numerical scale, the more variance, which allows for a relatively more nuanced response. More specific and candid feedback can be obtained by prompting directors to provide detailed freestyle commentary to explain a response on a numerical scale or to a “yes” or “no” question.

Well-drafted, targeted questions—or questions in the form of a statement—should be written specifically for the board, its committees and individual directors, as applicable, with the goal of eliciting valuable and practical feedback about board dynamics, operations, structure, performance and composition. High-quality feedback is what enables boards and directors to see how they can better perform and communicate, with the result that the company itself better performs and communicates.

Template evaluation questionnaires often do not demonstrate the strong potential of a well-drafted questionnaire. Many template questionnaires seem overlong and include unnecessarily hard- to-answer or unclear questions, such as “Does the board ensure superb operational execution by management?” These types of questions don’t seem to lend themselves to eliciting practical feedback. Complicated or unclear questions should be revised to be more practical or omitted from the questionnaire. Overlong questionnaires should be streamlined to be more relevant and effective in eliciting valuable and useful information.

Template evaluation questionnaires also often include numerous questions about clearly observable or known board and director attributes, practices and requirements. A short set of common examples includes:

I attend board meetings regularly

Advance meeting materials provide sufficient information to prepare for meetings, are clear and well-organized, and highlight the most critical issues for consideration

I come to board meetings well-prepared, having thoroughly studied all pre-meeting materials

The board can clearly articulate and communicate the company’s strategic plan

The board discusses director succession and has implemented a plan based upon individual skill sets and overall board composition

When evaluation questionnaires include numerous questions on observable practices or required duties and responsibilities, the evaluation becomes more of a checklist exercise than a serious effort to elicit valuable and useful information about how to improve board dynamics, operations, performance and composition. Overlong, vaguely worded, generic, checklist-type questionnaires can lead to director inattention and inferior feedback results, further impairing the evaluation process.

More effective questionnaires are purposefully and carefully drafted to focus director attention on matters that cut to the core of board and director performance. This may be facilitated when the questions focus succinctly on agreed-upon board goals and objectives or requirements and director qualifications considered together with the company’s performance and short- and long- term strategy.

For example, a written evaluation questionnaire need not ask whether the board and its directors have discussed and made a plan for director succession because the directors already know the answer. A better approach might be to recognize that such action did not take place and to ask each director, during a confidential interview process, “What factors or events distracted or prevented the board from discussing and implementing a plan for director succession?” Candid responses to that interview question should provide feedback that can uncover practices or leadership that should change in order to improve board performance.

Conducting confidential one‑on‑one interviews to elicit more candid feedback

Conducting well-planned, skillful interviews as part of the evaluation process can elicit more valuable, detailed, sensitive and candid director feedback as compared to questionnaires. The combined use of questionnaires and interviews may be most effective and, as noted above, was the approach disclosed by about one-quarter of Fortune 100 proxy filers. Fifteen percent of Fortune 100 proxy filers disclosed use of interviews only.

Interviews are particularly effective when there is an actual or potential issue of some sensitivity to address, as directors may prefer to discuss rather than write about sensitive topics. If boards believe interviews will be helpful, they should carefully consider who should conduct them—with the key criteria being that the interviewer is:

Well-informed about the company and its business environment as well as board practices

Highly trusted—even if not well-known—by the interviewees

Skilled at managing probing and candid conversations

Special considerations may arise when the interviewer is also part of the evaluation process. Where sensitivities like this are perceived, using an experienced and independent third-party interviewer can be effective.

While interviews do not enable anonymity, a trusted and skilled interviewer may still confidentially elicit valuable and sensitive feedback. Interviewer observations and interviewee feedback can be presented to the board without attribution.

Individual director self and peer evaluations

Individual self and peer evaluations—whether through questionnaires or interviews—can improve an evaluation process, especially one that is already generally successful as applied to the board as a whole and its committees. When directors understand and see value in evaluations at a collective level, they often perceive enhanced value in individual evaluations—both of themselves and of their peers.

Self-evaluations call for directors to be introspective about themselves and their performance and qualifications. Interestingly, simply being asked relevant questions about performance can lead directors to strive harder. The goal of self-evaluation is to enable directors to consider and determine for themselves during the evaluation process—and every other day—what they can proactively do to improve personal performance and better contribute to optimal board performance. Approximately one-quarter of Fortune 100 proxy filer boards included individual director self-evaluation in their evaluation process.

Peer evaluations increasingly are seen as critical tools to develop director skills and performance and promote more authentic board collaboration. A successful peer evaluation can also help improve director perspective. While some suggest that peer evaluations, even if provided anonymously, can be uncomfortable to provide and receive, a key characteristic of an effective board is that the board’s culture inspires and requires active, candid, relevant and useful participation from all members, as well as healthy debate and rigorous and independent yet collaborative decision-making. Where the board culture and dynamic are healthy, directors should see peer evaluation as important and beneficial guidance and coaching from esteemed colleagues. Ten percent of Fortune 100 proxy filer boards included peer evaluations in their evaluation process.

Using a third party

Use of third-party experts, such as governance advisory firms or external counsel, to facilitate the evaluation process is increasing. Twenty-two percent of Fortune 100 proxy filers disclosed having a third party facilitate their evaluation at least periodically, typically stated as every two or three years.

A third party can perform a range of evaluation services, from leading the evaluation process to conducting interviews to providing evaluation questions and reviewing questionnaire responses. Third parties can also help oversee implementation of evaluation action items.

Where the third party is independent of the company and the board, its participation in the evaluation process can meaningfully enhance the objectivity and rigor of the process and results. Third-party experts can provide new and different perspectives, both gained from work with other companies as well as simply being from outside the company, which can lead to improved action-item development and evaluation results.

The use of a third party may be especially helpful when:

The board wants to test or improve its existing evaluation process

Directors may not be forthcoming and candid with an internal evaluator

The board believes an independent third party can objectively bring new perspectives and issues to the board’s attention

The board is new or has undergone a significant change in composition and its directors are not yet poised to conduct an effective evaluation

The board has not seen significant change in composition over a period of time and new perspective is desired on board composition and performance

The company and its board are facing and addressing a crisis

Intra‑year evaluations and feedback

Board evaluations generally are performed annually. Common evaluation topics, however, relate to board practices and director attributes that are observable either in real-time, over a three- or six-month period, or with reference to board agendas and minutes. In such cases, boards should formally encourage real-time or prompt feedback to constructively address actual or potential issues. Indeed, doing so allows directors themselves to embody the “see something, say something” culture needed to promote long-term corporate value.

The concept of real-time or intra-year evaluation of board and director composition and performance is not new, even if not now widely practiced. A few (just under 10%) of proxy filers in the Fortune 100 disclosed that they carry out phases of the evaluation process on an ongoing basis, at every in-person meeting, quarterly, biannually or otherwise during the year.

Disclosing the evaluation process and evaluation results

A vast majority, 93%, of Fortune 100 proxy filers provide at least some disclosure about their evaluation process, but we observed wide variances in the scope and details of the disclosures.

Given the attention to board effectiveness, we expect companies will expand their disclosures relating to board evaluation and effectiveness.

About 20% of Fortune 100 proxy filers disclosed, at a high level, actions taken as a result of their board evaluation. Some examples include:

Enhanced director orientation programs

Changes to board structure and composition

Changes to director tenure or retirement age limits

Expanded director search and recruitment practices

Improvements to the format and timing of board materials

More time to review key issues like strategy and cybersecurity

Changes to company and board governance documents

Improved evaluation process

Conclusion

Investors, regulators, other company stakeholders and governance experts are challenging boards to examine and explain board performance and composition. Boards should address this challenge—first and foremost through a tailored and effective evaluation process. In doing this, boards can work to identify areas for growth and change to improve performance and optimize composition in ways that can enhance long-term value. Boards can also describe evaluation processes and high- level results to investors and other stakeholders in ways that can enhance understanding and trust.