Le séminaire à la maîtrise de Gouvernance de l’entreprise (DRT-7022) dispensé par Ivan Tchotourian*, professeur en droit des affaires de la Faculté de droit de l’Université Laval, entend apporter aux étudiants une réflexion originale sur les liens entre la sphère économico-juridique, la gouvernance des entreprises et les enjeux sociétaux actuels.

Le séminaire s’interroge sur le contenu des normes de gouvernance et leur pertinence dans un contexte de profonds questionnements des modèles économique et financier. Dans le cadre de ce séminaire, il est proposé aux étudiants depuis l’hiver 2014 d’avoir une expérience originale de publication de leurs travaux de recherche qui ont porté sur des sujets d’actualité de gouvernance d’entreprise.

Ce billet veut contribuer au partage des connaissances en gouvernance à une large échelle. Le présent billet est une fiche de lecture réalisée par messieurs Gabriel Béliveau et Carl Boulé sur le sujet de l’activisme actionnarial.

M. Gabriel Béliveau et M. Carl Boulé ont travaillé sur un article de référence des spécialistes du droit des sociétés que sont Paul Rose et Bernard Sharfman intitulé : « Shareholder Activism as a Corrective Mechanism in Corporate Governance ».

Dans le cadre de ce billet, les auteurs reviennent sur le texte pour le présenter, le mettre en perspective et y apporter un regard critique.

Bonne lecture ! Vos commentaires sont appréciés.

L’activisme actionnarial vu selon un mécanisme correctif de la gouvernance

Retour sur Shareholder Activism as a Corrective Mechanism in Corporate Governance de Paul Rose et Bernard Sharfman

par

Gabriel Béliveau et Carl Boulé

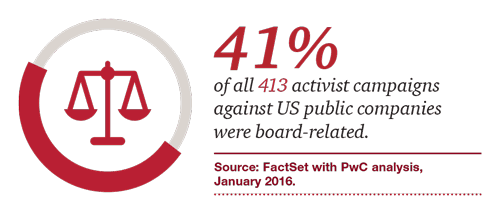

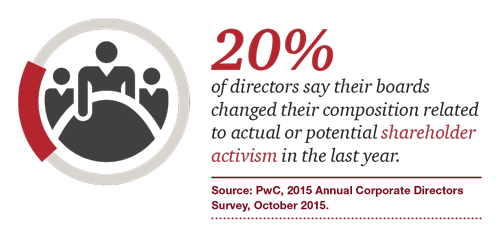

L’article « Shareholder Activism as a Corrective Mechanism in Corporate Governance » [1] rédigé par Rose et Sharfman s’inscrit dans le débat sur l’activisme actionnarial, notion réunissant « (…) toute action d’un actionnaire ou d’un groupe d’actionnaires visant à influencer une compagnie publique, sans pour autant tenter d’en prendre le contrôle » [2]. Plus précisément, les auteurs abordent la question de déterminer comment l’activisme actionnarial peut être employé afin de favoriser une gouvernance plus efficace. À cet égard, ils identifient une forme d’activisme permettant d’atteindre cet objectif : l’« offensive shareholder activism ».

Retour en terre connue

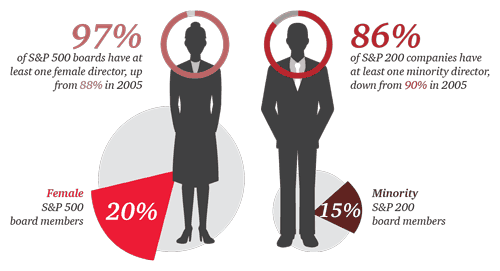

Les professeurs Rose et Sharfman amorcent leur analyse en portant leur attention sur l’encadrement juridique du pouvoir de gestion d’une société. Ils constatent que ce pouvoir est fortement centralisé entre les mains du conseil d’administration (ci-après « CA ») dont les membres sont élus périodiquement par les actionnaires. En raison d’une importante déférence accordée en sa faveur par le droit, le CA bénéficie d’une large marge de manœuvre dans la gestion de la société. Cette déférence a toutefois pour inconvénient de cautionner certaines erreurs que pourraient commettre les administrateurs. Elle laisse également planer un risque d’opportunisme de la part des membres du CA qui pourraient être tentés de faire primer leurs intérêts sur ceux de la société.

Offensive shareholder activism ?

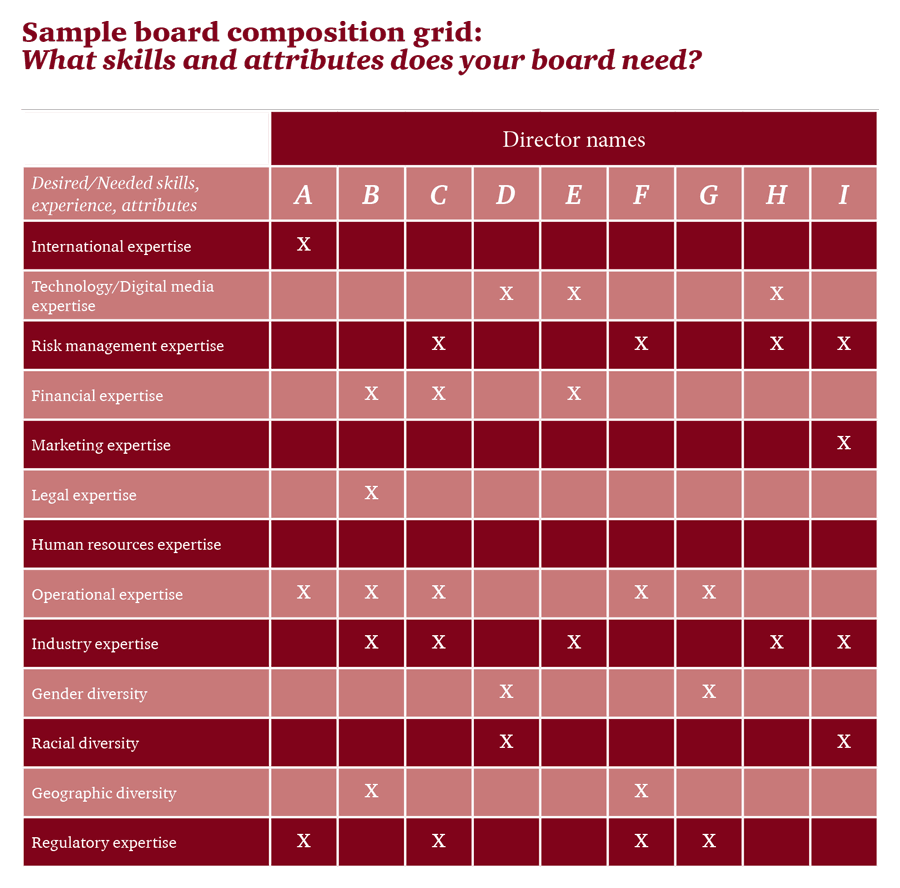

À l’aune de ces constats, les auteurs affirment que l’offensive shareholder activism entraîne un partage temporaire des pouvoirs de gestion qui permettrait de minimiser les inconvénients découlant de la gestion centralisée par le CA. Les auteurs poursuivent en expliquant que les résultats de l’activisme actionnarial dépendent grandement du type d’actionnaire qui est impliqué. Or, ils identifient cinq types d’actionnaires : les « insiders », les « liquidity traders », les « noise traders », les « market makers » et les « information traders ». Les insiders sont impliqués dans la gestion de l’entreprise et ont donc un devoir de réserve, ce qui fait qu’ils ne participent pas à l’activisme actionnarial. Les liguidity traders, les noise traders et les market makers ont tous des approches et des raisons d’investir différentes, mais se rejoignent par leur déficit informationnel à l’égard de certains enjeux pouvant concerner la société dans laquelle ils investissent. Ils ne sont donc habituellement pas impliqués efficacement dans l’activisme actionnarial et, pourtant, constituent souvent le groupe d’actionnaires pouvant faire pencher la balance lors de l’élection des administrateurs. Finalement, les information traders sont les actionnaires qui accordent le plus d’intérêt envers la gestion de l’entreprise. Il s’agit habituellement des investisseurs institutionnels, plus particulièrement, ceux appliquant des principes de gestion alternative (les « Hedge funds »). Ce sont ces derniers qui initient l’offensive shareholder activism.

Utilité de l’offensive shareholder activism

L’offensive shareholder activism résulte de la constatation par les cinq catégories d’actionnaires présentés ci-dessus que certains éléments internes d’une société l’empêchent de maximiser ses profits. Les activistes spécialisés de l’offensive shareholder activism détiennent parfois des informations précises concernant les tendances du marché ou la situation de concurrents, leur permettant de proposer des changements bénéfiques pour la société. Ces recommandations pourront ainsi contribuer à éclairer le CA, lui permettant de prendre des décisions plus éclairées. En effet, il arrive que le CA, trop concentré sur la gestion des affaires courantes et influencé par des considérations internes (gestion des ressources humaines, image de l’entreprise, vision des gestionnaires), ignore des opportunités stratégiques de croissance telles que la délocalisation, l’achat/vente, la restructuration ou l’établissement de mesures de responsabilité sociale de l’entreprise. Des études empiriques ont également démontré que l’offensive shareholder activism s’avère être une forme d’activisme actionnarial ayant un effet positif sur la valeur des actions [3]. Elles démontrent également que l’offensive shareholder activism permet l’accumulation de nouvelles informations utiles dans le processus de prise de décision [4].

Critiques de l’offensive shareholder activism

Les auteurs Rose et Sharfman remarquent que plusieurs spécialistes critiquent le concept général d’activisme actionnarial. En réponse aux voix qui, plus spécifiquement, lui reprochent une attitude fondée uniquement sur une vision à court terme, les auteurs rétorquent néanmoins que l’offensive shareholder activism se pratique selon un modèle d’affaires visant à cibler puis à redresser des éléments empêchant la valeur actionnariale d’une société de fructifier au maximum. Dès lors que l’empêchement a été traité, les actionnaires pratiquant l’offensive shareholder activism n’ont plus aucune raison de conserver leurs parts dans la société. De plus, les auteurs précisent que, contrairement à l’offensive shareholder activism, l’attitude passive des actionnaires ayant une vision à long terme n’amène aucun avantage à la gestion de la société. Qui plus est, des études démontrent la relative pérennité (sur une période de cinq ans) d’une portion des gains générés par l’offensive shareholder activism [5]. Finalement, Rose et Sharfman traitent des critiques voulant que les administrateurs s’avèrent mieux informés que les actionnaires quant aux activités de la société. Les administrateurs seraient a priori en meilleure pour en assurer la gestion de la société en continu. Bien qu’ils reconnaissent cette asymétrie, les auteurs la minimisent en précisant que l’offensive shareholder activism est pratiqué par des acteurs pouvant détenir une plus grande expertise sur certaines matières.

Au final, voici un article qui dans le contexte actuel si intense (et discuté) de l’activisme actionnarial [6] doit être lu avec intérêt !

[1] Paul Rose and Bernard S. Sharfman, « Shareholder Activism as a Corrective Mechanism in Corporate Governance », (2014) 5 BYU Law Review 1015.

[2] La compagnie publique est celle ayant fait « appel public à l’épargne », de façon analogue à ce que prévoient, au Québec, la Loi sur les valeurs mobilières, RLRQ c. V-1.1 et ses règlements.

[3] Alon Brav, Wei Jiang, Frank Partnoy and Randall Thomas, « Hedge Fund Activism, Corporate Governance, and Firm Performance », (2008) 63 J. FIN. 1729 ; Nicole M. Boyson and Robert M. Mooradian, « Experienced Hedge Fund Activists », (2012) AFA Chi. Meetings Paper, http://ssrn.com/abstract=1787649.

[4] Sanford J. Grossman and Joseph E. Stiglitz, « On the Impossibility of Informationally Efficient Markets », (1980) 70 AM. ECON. REV. 393 ; Bernard S. Sharfman, « Why Proxy Access is Harmful to Corporate Governance », (2012) 37 J. CORP. L. 387.

[5] Alon Brav, Wei Jiang, Frank Partnoy and Randall Thomas, préc. note 3, p. 1735 ; Nicole M. Boyson, Linlin Ma and Robert Mooradian, « Are All Hedge Fund Activists Created Equal? The Impact of Experience on Hedge Fund Activism », (2014) Inaugural Financial Market Symposium, School of Business State University of New York ; Lucian A. Bebchuk, Alon Brav and Wei Jiang, « The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism » (2014) Columbia Business School, Research Paper No 13-66, http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2291577.

[6] Pour des illustrations récentes de comportement court-termiste des activistes, voir : Andrew R. Sorkin, « “Shareholder Democracy” Can Mask Abuses », The New York Times (25 février 2013). Pour les discussions récentes sur les objectifs attachés à l’activisme des fonds de couverture aux États-Unis, voir : Martin Lipton, « The Threat to Shareholders and the Economy from Activist Hedge Funds » (14 janvier 2015), The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation, http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/corpgov/2015/01/14/the-threat-to-shareholders-and-the-economy-from-activist-hedge-funds/ ; Lucian A. Bebchuk, Alon Brav and Wei Jiang, préc. note 4 ; Francis Byrd, Drew Hambly and Mark Watson, « Short-Term Shareholder Activists Degrade Creditworthiness of Rated Companies », Commentaire spécial, Moody’s Investors Services, 2007. Au Canada, voir : Yvan Allaire, The case for and against activist hedge funds, IGOPP Policy Paper, IGOPP, Montreal, 2014, http://igopp.org/en/the-case-for-and-against-activist-hedge-funds-2/. En France, voir Laurence Boisseau, « Attaques des fonds activistes : des effets controversés à long terme », Les Échos.fr, (22 janvier 2015), http://www.lesechos.fr/22/01/2015/lesechos.fr/0204102535772_attaques-des-fonds-activistes—des-effets-controverses-a-long-terme.htm.

*Ivan Tchotourian, professeur en droit des affaires, codirecteur du Centre d’Études en Droit Économique (CÉDÉ), membre du Groupe de recherche en droit des services financiers (www.grdsf.ulaval.ca), Faculté de droit, Université Laval.