Board’s Role and Director Duties Remain Durable

While the corporate governance environment is always changing, board responsibilities and the fiduciary duties of directors under state corporate law have proven remarkably durable. Directors must:

Manage or direct the affairs of the company and cannot abdicate that responsibility by deferring to shareholder pressure.

Act with due care, without conflict, in good faith, and in the company’s best interest.

Delegate and oversee management of the company (for example, by selecting the CEO, monitoring the CEO’s performance, and planning for succession), and oversee strategy and risk management.

Ensuring that the day-to-day management of the company is in the right hands, providing management with forward-looking strategic guidance, and monitoring management’s efforts to identify and manage risk, including risks that pose an existential threat, remain at the heart of the board’s role. To accomplish this, boards need to understand and address disruptive risks. Boards should be mindful that adequate time is reserved on the agenda for these matters, with less focus on formal management presentations and more focus on the problems and concerns management is grappling with.

The National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) Blue Ribbon Commission recently provided guidance on oversight of risks that pose an existential threat (NACD, Adaptive Governance: Board Oversight of Disruptive Risks (Oct. 2018), available at nacdonline.org). The Commission recommends that boards prioritize certain actions, including:

Understanding and addressing disruptive risks “in the context of the [company’s] specific circumstances, strategic assumptions, and objectives.”

Allocating oversight of disruptive risks between and among the full board and its committees, and clarifying the allocation of responsibilities in committee charters.

Recognizing that enterprise risk management processes may not capture disruptive risks.

Evaluating board culture regularly for “openness to sharing

concerns, potential problems, or bad news; response to mistakes; and acceptance of nontraditional points of view.”

Assessing “leadership abilities in an environment of disruptive risks” in CEO selection and evaluation processes.

Aligning the company’s “talent strategy” with “the skills and structure needed to navigate disruptive risks.”

Refraining from automatically re-nominating directors as a “default decision.”

Treating board diversity as “a strategic imperative, not a compliance issue.”

Requiring continuing learning of all directors, and assessing that factor in the board’s evaluation process.

Ensuring risk reports provide “forward-looking information about changing business conditions and potential risks in a format that enables productive dialogue and decision making.”

Holding a substantive discussion, at least annually, of the company’s vulnerability to disruptive risks, “using approaches such as scenario planning, simulation exercises, and stress testing to inform these discussions.”

Shareholder Primacy and Shareholder Influence Under Scrutiny

While it is prudent for directors to listen to and engage with shareholders and understand their interests, directors must apply their own business judgment and determine what course is in the best interests of the company. This means that they cannot merely succumb to pressures from activist investors and other shareholders (see, for example, In re PLX Tech., Inc. Stockholders Litig., 2018 WL 5018535, at *45 (Oct. 16, 2018) (an activist “succeeded in influencing the directors to favor a sale when they otherwise would have decided to remain independent” and the incumbent directors improperly deferred to the activist and allowed him “to take control of the sale process when it mattered most”)).

However, shareholders have gained considerable power relative to boards over the last 20 years, making it difficult to resolve shareholder pressures that conflict with director viewpoints regarding the best course for the company. The forces that have strengthened shareholder influence include:

Concentration of shareholding in the hands of powerful institutional investors (with institutions owning 70% of US public company shares in 2018).

The activation of institutional investors regarding proxy voting (with institutional voting participation at 91% compared to retail shareholder participation at 28%).

The rise of proxy advisory firms that serve to coordinate proxy voting.

The dismantling of classic corporate defenses, such as classified boards and poison pills.

The rise in shareholder engagement and negotiation (or “private ordering”) of governance processes. (Broadridge, 2018 Proxy Season Review (Oct. 2, 2018), available at broadridge.com.)

While there is no sign that shareholder influence will dissipate, recent legislative developments suggest that shareholder primacy (the premise that a company is run for the benefit of its shareholders in the first instance) is under some pressure. For example, in August 2018, US Senator Elizabeth Warren proposed the Accountable Capitalism Act, which among other things would require directors of US companies with $1 billion or more in annual revenues to obtain a charter as a “United States Corporation” and consider the interests of all corporate stakeholders, including employees, customers, and communities, in their decision-making, in addition to the interests of shareholders. (S. 3348, 115th Cong. § 5(c)(1)(B) (2017–2018); for more information, search Looking Ahead: Key Trends in Corporate Governance on Practical Law.)

In addition, there are increasing calls for the responsible use of power by large institutional investors, which have a considerable and growing influence on the companies in which they invest. The underlying concern is the responsible use of significant economic power, given the substantial impact on society that large institutional investors and companies have. For example, in January 2018, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink wrote to the CEOs of BlackRock portfolio companies that “society increasingly is turning to the private sector and asking that companies respond to broader societal challenges. … To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society. Companies must benefit all of their stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate” (Annual Letter to CEOs from Larry Fink, Chairman and CEO, BlackRock, available at blackrock.com).

This broader view of a company’s purpose recognizes that, while social interests and shareholder interests are often viewed as in tension, outside of a short-term perspective social interests and shareholder interests tend to align. For pension funds and many other institutional investors, the interests of their beneficiaries are aligned with the successful performance of healthy companies over a period of years.

Given the size of institutional investors’ portfolios, they face challenges in applying their influence on a company-specific basis. While some of the largest institutional investors are investing in the human resources and technology needed to make informed voting decisions on a case-by-case, company-specific basis, with respect to a large number of companies in their portfolios, many institutional investors still apply set policies on a one-size-fits-all basis, without nuanced analysis of the circumstances, in voting their shares. Institutional investors should assess whether they:

Are well positioned to vote their shares on an informed basis.

Have designed screens that consider company performance and other factors that may support a change from standard policy, if relying on the application of pre-set policies.

When institutional investors turn to proxy advisory firms to make voting decisions, they should evaluate how the proxy advisor is positioned to make sophisticated and nuanced case-by-case determinations, and whether resource constraints require the proxy advisor to rely heavily on the use of set policies (see below Convergence of Ideas on Corporate Governance Practices Continues).

In January 2017, a group of institutional investors launched the Investor Stewardship Group (ISG) and issued Stewardship Principles and Corporate Governance Principles that took effect on January 1, 2018 (available at isgframework.org). The Stewardship Principles set forth a stewardship framework for institutional investors that includes the following principles:

Principle A: Institutional investors are accountable to those whose money they invest.

Principle B: Institutional investors should demonstrate how they evaluate corporate governance factors with respect to the companies in which they invest.

Principle C: Institutional investors should disclose, in general terms, how they manage potential conflicts of interest that may arise in their proxy voting and engagement activities.

Principle D: Institutional investors are responsible for proxy voting decisions and should monitor the relevant activities and policies of third parties that advise them on those decisions.

Principle E: Institutional investors should address and attempt to resolve differences with companies in a constructive and pragmatic manner.

Principle F: Institutional investors should work together, where appropriate, to encourage the adoption and implementation of the Corporate Governance Principles and Stewardship Principles.

Reform of Proxy Voting and Regulation of Proxy Advisors Under Consideration

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) staff recently held a roundtable to assess whether the SEC should update its rules governing proxy voting mechanics and the shareholder proposal process, and strengthen the regulation of proxy advisory firms. These issues have been under consideration since the SEC solicited public comment on the proxy system in 2010. (SEC, November 15, 2018: Roundtable on the Proxy Process, available at sec.gov; Concept Release on the U.S. Proxy System, 75 Fed. Reg. 42982-01, 2010 WL 2851569 (July 22, 2010).)

Topics discussed at the roundtable included:

Proxy voting mechanics and technology. Panelists agreed that the current proxy voting system needs to be modernized and simplified, for example, by:

implementing a vote confirmation process so that shareholders may verify, before the vote deadline, that voting instructions were followed and their votes were counted;

using technology to encourage wider participation and reduce costs and delays in the voting process;

studying why retail shareholder participation has fallen and whether more direct communication channels would improve information flow and participation; and

mandating use of universal proxy cards in proxy contests.

The shareholder proposal process. Some panelists asserted that the current shareholder proposal process functions well, while others identified areas for reform, including:

revisiting the ownership thresholds and holding period required to submit a shareholder proposal (currently, the lesser of $2,000 or 1%, and one year);

increasing resubmission thresholds to address reappearance of a proposal even though a majority of shareholders voted it down year after year;

providing more SEC guidance on no-action decisions and rationales;

requiring proxy disclosure of the name of the shareholder proponent (and its proxy, if any) and its level of holdings; and

requiring disclosure of preliminary vote tallies.

The role and regulation of proxy advisory firms. While no significant consensus emerged regarding whether proxy advisory firms should be subject to further SEC regulation, areas under discussion included:

improving accuracy of proxy advisor reports and affording all companies opportunities to review and verify information in advance of publication; and

improving procedures to monitor and manage, and enhancing disclosure of, conflicts of interest.

The Corporate Governance Reform and Transparency Act

The Corporate Governance Reform and Transparency Act, H.R. 4015, would require proxy advisory firms to register with the SEC, which would require:

Sufficient staffing to provide voting recommendations based on current and accurate information.

The establishment of procedures to permit companies reasonable time to review and provide meaningful comment on draft proxy advisory firm recommendations, including the opportunity to present (in person or telephonically) to the person responsible for the recommendation.

The employment of an ombudsman to receive and timely resolve complaints about the accuracy of voting information used in making recommendations.

Policies and procedures to manage conflicts of interest.

Disclosure of procedures and methodologies used in developing proxy recommendations and analyses.

Designation of a compliance officer responsible for administering the required policies and procedures.

Annual reporting to the SEC on the proxy advisory firm’s recommendations, including the number of companies that are also consulting division clients, as well as the number of proxy advisory firm staff who reviewed and made recommendations.

The bill would also direct the SEC staff to withdraw two no-action letters issued by the SEC in 2004, which the fact sheet suggests “have led to overreliance on proxy advisory firm recommendations.” (The SEC rescinded those two no-action letters in September 2018.)

The bill is supported by both Nasdaq and the New York Stock Exchange, as well as leading business groups and the Society for Corporate Governance. It is opposed by the Council of Institutional Investors, the Consumer Federation of America, and many public pension fund managers.

(See, for example, Nelson Griggs, Nasdaq, U.S. House of Representatives Passes Proxy Advisory Firm Reform Legislation (Dec. 16, 2017), available at nasdaq.com; Council of Institutional Investors, CII Urges Members to Contact Congressional Reps, Opposing Proxy Advisors Bill (Jan. 13, 2018), available at cii.org.) The bill is unlikely to be passed into law before the current congressional term ends, but may be reintroduced during the following congressional term.

It remains to be seen whether the SEC will incorporate input from the roundtable into future rulemaking or new SEC staff guidance or practice. The SEC is more likely to focus on proxy reform as a priority than on regulation of proxy advisory firms absent pressure from Congress.

Two bills seeking SEC regulation of proxy advisory firms were introduced in the 115th Congress:

The Corporate Governance Reform and Transparency Act, H.R. 4015. In June 2018, the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs held a hearing on this bill, which was sent by the House of Representatives to the Senate in December 2017 for consideration. (See Box, The Corporate Governance Reform and Transparency Act.)

The Corporate Governance Fairness Act, S. 3614. In November 2018, this bill was introduced in the Senate to amend the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (Advisers Act) to expressly require proxy advisory firms to register as investment advisers under the Advisers Act, thereby subjecting them to enhanced fiduciary duties and SEC oversight, including regular SEC staff examinations into their conflict of interest policies and programs, and whether they knowingly have made false statements to clients or have omitted to state material facts that would be necessary to make statements to clients not misleading.

Both bills would subject proxy advisory firms to SEC regulation, and focus on policies and procedures regarding conflicts of interest and accuracy. H.R. 4015 goes further by mandating

maintenance of certain staffing levels and annual reporting relating to recommendations. Neither bill is likely to be passed into law by the end of the current session of Congress.

Convergence of Ideas on Corporate Governance Practices Continues

Proxy advisory firms are often criticized for imposing a one-size-fits-all view of corporate governance on public companies in the US. However, the divide is narrowing between what investors and their proxy advisors, on the one hand, and corporate directors and CEOs, on the other hand, think are good corporate governance practices.

Recently, a high-profile group of senior executives from major public companies and institutional investors issued the Commonsense Principles 2.0 to revise corporate governance principles that the group published in 2016 (available at governanceprinciples.org). The Commonsense Principles 2.0 describe corporate governance practices that have become widely accepted among leading companies and their institutional investors, including in previously controversial areas such as majority voting in uncontested director elections and proxy access. A majority of S&P 500 companies already practice most of the recommendations, and many of the recommendations are requirements for publicly traded companies under SEC regulations or stock exchange listing rules. For example, the Commonsense Principles 2.0 provide that:

One-year terms for directors are generally preferable, but if a board is classified, the reason for that structure should be explained.

The independent directors should decide whether to have combined or separate chair and CEO roles based on the circumstances. If they combine the chair and CEO roles, they should designate a strong lead independent director. In any event, the reasons for combining or separating the roles should be explained clearly.

A director who fails to receive a majority of votes in uncontested elections should resign and the board should accept the resignation or explain to shareholders why it is not accepted.

These recommendations are in line with evolving practices.

The Commonsense Principles 2.0 address some recommendations to institutional investors and asset managers, and call on them to use their influence transparently and responsibly. Among other things, they urge asset managers to disclose their proxy voting guidelines and reliance on proxy advisory firms, and be satisfied that the information that they are relying on is accurate and relevant.

Notably, the Commonsense Principles 2.0 reflect the convergence of viewpoints through agreement among a coalition of high-profile leaders of well-known public companies, institutional investors, and one activist hedge fund. Signatories include Mary Barra of General Motors, Ed Breen of DowDupont, Warren Buffet of Berkshire Hathaway, Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase, Larry Fink of BlackRock, Bill McNabb of Vanguard, Ronald O’Hanley of State Street, and Jeff Ubben of ValueAct Capital. The Council of Institutional Investors and the Business Roundtable have expressed support for or endorsed the Commonsense Principles 2.0.

Shifting Focus of Private Ordering to ESG Issues

The convergence of views among corporate leaders and large institutional investors on corporate governance practices reflects to a significant degree the success shareholders have had in influencing corporate governance reforms through engagement with boards, or private ordering. Shareholders are continuing to engage companies and press for reforms in the areas of shareholder rights and board composition and quality, but they are also increasing their focus on ESG issues, such as climate change, diversity, and board effectiveness, and the impact of ESG issues on companies’ financial performance. ESG is no longer a fringe issue of interest only to special issue investors. Mainstream institutional investors are recognizing that attention to ESG and corporate social responsibility impacts portfolio company financial performance.

The rising interest in ESG among investors is apparent in the sharp rise in US-domiciled assets under management using ESG strategies ($12.0 trillion at the start of 2018, up 38% since 2016 and an 18-fold increase since 1995, as reported by the US SIF Foundation), increasing support for shareholder proposals relating to ESG issues, as well as in the focus of engagement efforts. According to Broadridge, institutional investor support for social and environmental proposals increased from 19% in 2014 to 29% in 2018 (Broadridge, 2018 Proxy Season Review (Oct. 2, 2018), available at broadridge.com).

Continuing Demand for Shareholder Engagement and Attention to Activist Investors

In this era of enhanced shareholder influence, directors need to be especially attuned to the interests and concerns of significant shareholders, while continuing to apply their own judgment about the best interests of the company. This requires active outreach and engagement with the company’s core shareholders and, in particular, the persons responsible for voting proxies and setting the governance policies that often drive voting decisions. Caution, balance, and effective communication are also necessary to ensure that director judgment is not replaced with shareholder appeasement.

In the first half of 2018, record numbers of hedge fund activist campaigns were launched, backed by record levels of capital. Activist investors are having greater success in negotiating board seats and in winning seats in contested elections. The general level of vote support for directors is falling. For example, 416 directors failed to receive majority shareholder support in the 2018 proxy season (an 11% increase over 2017) and 1,408 directors failed to attain at least 70% shareholder support (a 14% increase over 2017) (Broadridge, 2018 Proxy Season Review (Oct. 2, 2018), available at broadridge.com).

Understanding key shareholders’ interests and developing relationships with long-term shareholders can help position the company to address calls by activist investors for short-term actions that may impair long-term value. However, boards also should view the input they receive from activist investors as valuable, because it could help identify potential areas of vulnerability. Moreover, establishing an open and positive dialogue with activist investors, and engaging with them in meaningful discussions, can assist boards in avoiding a public shareholder activist campaign in the future. This requires:

Identifying the company’s key shareholders and the issues about which they care the most.

Objectively assessing strategy and performance from the perspective of an activist investor, including proactively identifying areas in which the company may be subject to activism.

Monitoring corporate governance benchmarks and trends in shareholder activism to keep abreast of “hot topic” issues.

Comparing the company’s corporate governance practices to evolving best practice.

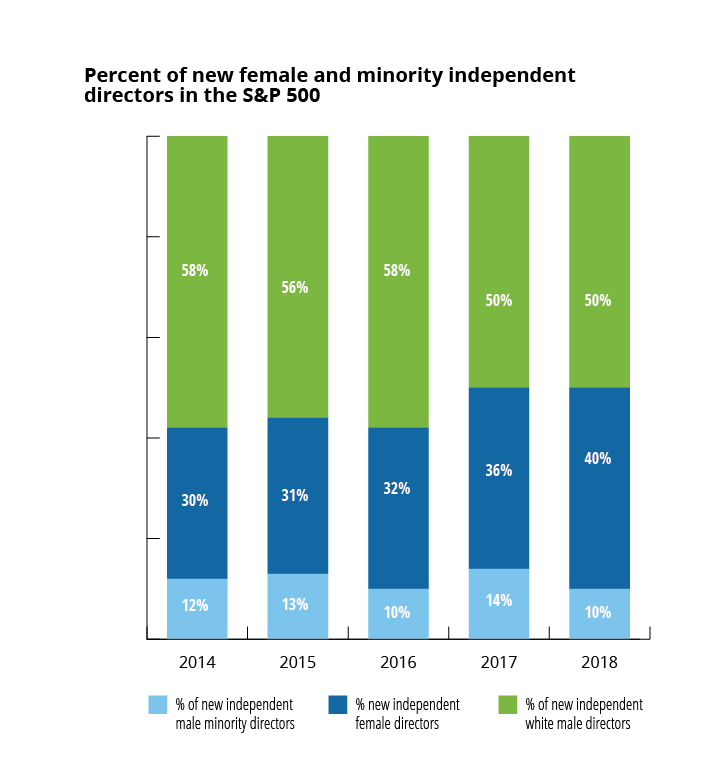

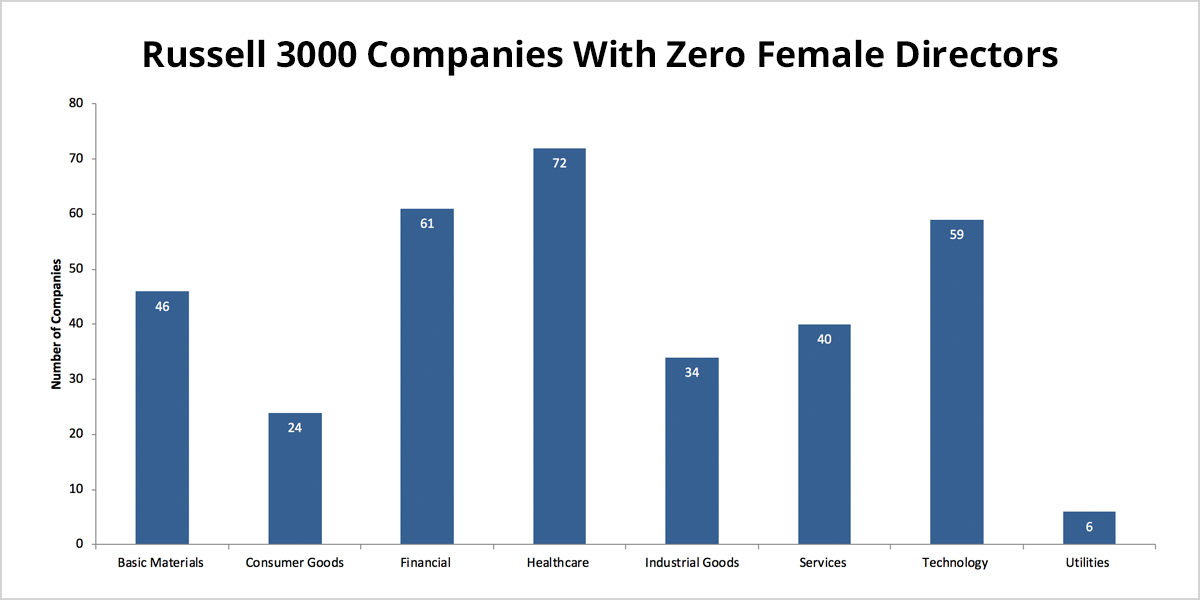

Attending to potential vulnerabilities in board composition. Activist investors scrutinize the tenure, age, demographics, and experience of each director. They will target directors whose expertise is arguably outdated, who have poor track records as officers or directors of other companies, or who have served on the board for long tenures. They will also look for gaps in the expertise needed by the board given the current dynamic business environment, and for a lack of gender or ethnic diversity. Boards should monitor developments in these areas (see, for example, Institutional Shareholder Services Inc. (ISS), 2019 ISS Americas Policy Updates (Nov. 19, 2018), available at issgovernance.com (announcing that, beginning in 2020, ISS will oppose the nominating committee chair at Russell 3000 or S&P 1500 companies when there are no women on the board); 2018 Cal. Legis. Serv. ch. 954 (S.B. 826) (to be codified at Cal. Corp. Code §§ 301.3, 2115.5) (mandating gender quotas for boards of US public companies that are headquartered in California)).

Addressing potential vulnerabilities in CEO compensation, including disparity with respect to peer companies and other named executive officers. Activist investors could claim that this signals a culture in which too much deference is given to the CEO and there is a lack of team emphasis in the compensation of management.

Reviewing structural defenses with the assistance of seasoned proxy fight and corporate governance counsel. Many companies have not reviewed their charter and bylaws recently, and in a proxy contest the language of many bylaw provisions can take on a different meaning. Boards should be aware that proxy advisory firm ISS recently announced that it will generally oppose management proposals to ratify a company’s existing charter or bylaw provisions, unless the provisions align with best practice (2019 ISS Americas Policy Updates, at 11).

Effectively communicating long-term plans with respect to strategy and performance pressures, defending past performance, and addressing calls for an exploration of strategic alternatives.

Preparing a response plan for engaging with activist investors to ensure that the board and management convey a measured and unified position.

Furthermore, the pay can be decent, judging from the NACD and Pearl Meyer & Partners

Furthermore, the pay can be decent, judging from the NACD and Pearl Meyer & Partners