The information asymmetry between corporations and investors is particularly severe regarding long-term strategic plans: existing market infrastructure for disclosure is very short-term focused and underserves sources of long-term value creation. The CEO-delivered long-term plan gives corporations an opportunity to reorient disclosures to the long-term. The Strategic Investor Initiative provides comprehensive guidance to CEOs and their Investor Relations teams on the key components of a long-term plan—set out in our Investor Letter to CEOs.

Through feedback from institutional investors we have identified content elements essential to an effective investor-facing CEO-delivered long-term plan:

- Additive to existing disclosures: Add information to the public domain or provide additional context for existing disclosures.

- More than marketing—contextualized disclosures: A strategic plan narrative is not a recitation of good news stories. Initiatives should be contextualized to help investors assess their significance.

- Focused by materiality: A long-term plan should disclose information that is material to the operating performance and financial prospects of the business.

- Integrated discussion of material Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) issues: Part of an integrated discussion—not a silo or presented as a list of “awards.”

- Forward looking information: A long-term plan is an opportunity for a company to meaningfully talk about the future across a broad range of value-relevant topics, accompanied by goals, metrics and milestones.

Emerging Practice in Long-Term Plans—By Key Theme

In this paper we set out key themes that CEOs have addressed in their long-term plan presentations delivered at CEO Investor Forums convened by the Strategic Investor Initiative. We identify why each theme is an enduring subject of investor interest (and identified in our Investor Letter to CEOs) and provide examples from CEO presentations of content that was well-received by institutional investors. We also provide suggestions of key additions that CEOs can make to enhance the utility of disclosures on these key themes:

- Risk factors and mega-trends: Highlights presentations by Delphi and PG&E

- Corporate governance: Highlights presentations by Medtronic and Merck

- Capital allocation: Highlights the presentation by Becton Dickinson

- Human capital management: Highlights the presentation by Aetna

- Shareholder and stakeholder engagement: Highlights the presentations by Merck, Telia, and Prudential

We are delighted to feature Insights from FCLTGlobal in the corporate governance theme.

Introduction: The Long-Term Imperative

A gap exists between a corporation’s knowledge of its practices and prospects and the knowledge of its investors. Periodic disclosures are intended to reduce the level of this information asymmetry. This structural information gap between corporations and investors appears particularly severe regarding forward-looking information about a corporation’s long-term strategic plans—an issue long-term institutional investors are increasingly vocal about wanting companies to address.

Corporations endure, and often plan, over decades through long-term-focused management and strategic planning processes. Although a strategic plan can address periods of 3, 5, or 15 years, corporations tend to communicate in quarters (through the 10-Q and earnings call).

Some corporations do, of course, communicate with investors through a variety of other forums (in addition to the earnings call), including investor days, industry conferences, and, increasingly, common year-round bilateral engagements, in addition to mandatory disclosures such as the 10-K and voluntary disclosures, such as sustainability reports. However, the landscape of corporate communications with shareholders does not include a disclosure venue focused on long-term sustainable value creation. The existing market infrastructure for disclosure remains very short-term focused and the mix of information provided underserves sources of long-term value creation—to the continuing of frustration of long-term institutional investors.

Through our convening of CEO Investor Forums, we provide a venue for a curated conversation between leading CEOs and long-term investors to help plug an unmet need for information with a long-term time horizon and reorient capital markets toward the long term. To date, over 25 companies (representing over $2 trillion in market cap) have presented long-term plans at a CEO-Investor Forum to an investor audience representing in excess of $25 trillion in AUM.

In this paper, we set out examples of emerging practices in CEO-presented long-term plans, identify core investor content expectations, and highlight how CEOs are seeking to tackle key themes for improved corporate disclosure. We hope both investors and corporations find it useful.

Six Reasons Companies Should Share Their Long-Term Thinking

- To demonstrate that there is an effective long-term strategy

- To show that the company can anticipate and capitalize on mega-trends

- To help investors understand ESG issues “through the eyes of management”

- To encourage the C-Suite to reflect on the corporate ecosystem, including a consideration of its stakeholders

- To help inspire—and retain—both employees and investors over the long-term

- To foster leadership in corporate-shareholder communications

Adapted from “Far Beyond the Quarterly Call: CECP’s first CEO Investor Forum” published in the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance

SII’s Investor Letter to CEOs

In the Strategic Investor Initiative’s Investor Letter to CEOs, signed by Bill McNabb and nine leading institutional investors, we ask CEOs to present their long-term plans for sustainable value creation at our CEO Investor Forums.

The letter asks CEOs to: set out a long-term plan with a five-year trajectory accompanied by goals, metrics and milestones; offer commentary on the role of the board in formulating and monitoring strategy; discuss financially material risks and the firm’s framework for identifying material ESG risks; and review the company’s capital allocation strategy.

The Themes of the Seven Questions Every CEO Should Be Able to Answer

How Do These Themes Connect to Long-Term Strategy:

- Risk factors and mega-trends

- Corporate purpose and role in society

- Frameworks for shareholder engagement

- Financially material business issues and frameworks for identifying those issues

- Human capital management

- Board composition

- Role of the board

Investor Feedback: Helping CEOS Meet Investors’ Content Expectations

CEO-delivered long-term plans can help plug a gap in existing market infrastructure and help meet the information needs of long-term investors. To date, we’ve received feedback, both in person and online, from hundreds of institutional investors on the long-term plans presented at CEO Investor Forums. We asked these investors to identify in each CEO presentation the themes that were most useful and the themes that were least useful for informing their investment outlook, voting, and engagement activities.

Building on this investor feedback, we have identified content elements essential to an effective investor-facing long-term plan—in addition to the expectations set out in our Investor Letter to CEOs:

Additive to existing disclosures: A long-term plan should add information to the public domain or provide additional contextualizing commentary to such existing disclosures (e.g., build on disclosures made at the investor day or in other disclosure forums).

More than marketing—Contextualized disclosures: a strategic plan narrative is not a recitation of good news stories. A long-term plan presentation is an opportunity to delineate key risks and challenges facing the business and to help investors see those issues “through the eyes of management,” given management’s “unique perspective on its business that only it can present.” Highlighting key initiatives within the business is useful for expanding investor understanding. However, to avoid being dismissed as marketing, such initiatives should be contextualized to help investors assess their significance within the business.

Focused by materiality—A long-term plan should disclose information that is material to the operating performance and financial prospects of the business over the long term. Material business issues tend to vary systematically by sector, giving management an opportunity to provide a focused presentation on issues of enduring investor interest and relevance for that sector. The disclosure framework provided by the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) gives corporations a method to identify and organize such disclosures in a way relevant to investors.

Integrated discussion of material ESG issues—These issues are widely acknowledged as core to business success over the long term. As a result, ESG issues should be part of an integrated discussion—not be placed in a silo or presented as list of “awards.”

Forward looking information—Corporate disclosure abounds with backward-looking information. A long-term plan is an opportunity for a company to meaningfully talk about the future across a broad range of value-relevant topics, accompanied by goals, metrics, and milestones.

Least Useful CEO Disclosures

- Disclosures unconnected to long-term strategy

- Sustainability presented as a silo or eye-catching initiatives without adequate context

- Extended commentary on the history of the corporation

- Discussions of “corporate purpose” unconnected to operations and strategy

- Extended discussion of issues immaterial to the industry or sector

Emerging Practice in Long-Term Plans: Early Evidence From a Year of CEO Investor Forums

The long-term plan is an experimental form. CEOs who have presented their corporations’ plans to date have been guided by our Investor Letter to CEOs—but they do have broad flexibility to set out their corporations’ authentic long-term narratives.

Set out below are key themes addressed in long-term plans presented at our CEO Investor Forums and examples of how companies have tackled those themes. In each case, we identify the broad market need for such information and why it is relevant to long-term-focused investors.

Risk Factors and Mega-Trends

Leading executives spend much of their time addressing long-term business issues and strategy with their teams—and increasingly with their boards. Such thinking requires a consideration of the mega-trends impacting the operating model, product markets, and geographies in which their company operates. Capitalizing on these long-range trends is a key informing context for the development of a corporation’s strategic plan and the capital allocation decisions that will enable the plan to be implemented.

To date, existing disclosures have not proved effective in enabling corporations to talk about these long-term, forward-looking trends with their investors—and, when disclosures are made on these topics, they tend to be of low utility to investors.

For example, the MD&A section of the 10-K 9 requires disclosures regarding “known trends and uncertainties.” In considering disclosure, the corporation is asked to assess the likelihood of the trend occurring and, if it is reasonably likely to occur, seek to quantify the potential impact of that trend. This gives a corporation an opportunity to reflect on long-range trends—information highly valuable to investors. The wide discretion provided by the two-part materiality determination significantly reduces the extent of such disclosures, which also tend to be static—with only a small percentage of firms making significant changes to MD&A language over time. Risk factor disclosures are also a requirement in the 10-K. Specific risk factor disclosures are decision-relevant to investors.

However, disclosures of risk factors often lack corporation-specific elements, tend toward generic or vague language—best characterized as boilerplate—drafted more as a litigation shield than as a medium through which to inform investors.

As a result, existing disclosures inadequately capture the elements and outcomes of the strategic planning process and often fail to address long-range trends (whether market, environmental or societal) in a manner useful to investors.

| Mega-trends Identified at CEO Investor Forums: |

Investor Letter Question: |

- The transition to a low-carbon economy (PG&E)

- Disruption and democratization of product markets (UPS)

- Aging societies (BD)

- Unsustainable health care systems (Aetna, Medtronic)

- Technology amplifying corporate risk from cybersecurity to reputation (Delphi)

|

Mega-trends“What are the key risk factors and mega-trends (such as climate change) your business faces over the next three to seven years and how have these influenced corporate strategy?” |

Mega-trends represent a formidable set of financial, operational, governance, and policy challenges; these cross-cutting issues vary in intensity by sector.

Kevin Clark of Delphi highlighted how the major disruptions of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, such as AI and drive-train electrification, are changing the nature of the automobile—and, consequently, the nature of the automobile technology business. Clark identified the mega-trends of “Safe, Green, and Connected” that are broadly impacting the automotive sector and sought to identify how trends were having impacts on long-term strategy across the business. One element identified was the extent to which new technology required significant adjustments in workplace skills and recruitment patterns. Delphi had responded to these new requirements through collaborations in “talent rich” recruitment markets among other initiatives.

Anthony Earley and Geisha Williams of PG&E structured their presentations in the context of the transition to a low-carbon economy in both energy generation and transport and highlighted how that trend was driven by regulation, the urgency of climate change, and consumer demand. That overview was contextualized by commentary on PG&E’s science-based emission reduction targets and proportion of renewable energy in its overall energy generation mix. Both presentations set out comparisons of carbon intensity with peer utilities and identified the trajectory of future energy generation and use.

Examples of Key Issues for Discussion in “Mega-Trends and Key Risks”

Climate Change and Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD): In those sectors with large exposures to issues involved in climate change, investors expect a structured discussion on the implications of climate change.

The TCFD provides a four-part framework through which corporations can address climate change:

- Governance

- Strategy

- Risk management

- Metrics and targets

Commentary, structured around the operating model of the business, enables investors to assess whether climate change adaptation is being implemented at an adequate scale and the extent of exposures to related risks, such as regulatory change.

The extent of scenario analysis conducted and the assumptions underlying it gives investors critical visibility into a corporation’s preparedness for climate change under various scenarios. Given the board-centric view of many long-term investors, commentary around the governance arrangements for assessing and responding to climate risk is particularly well received.

Corporate Governance: Long-Term Strategy, Compensation, and Composition

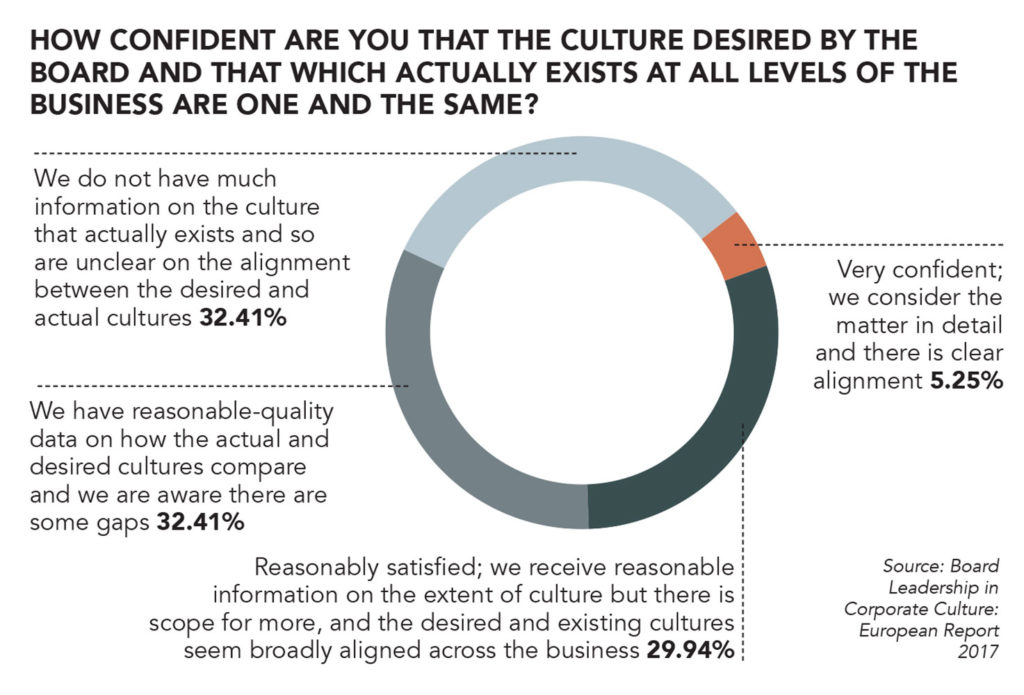

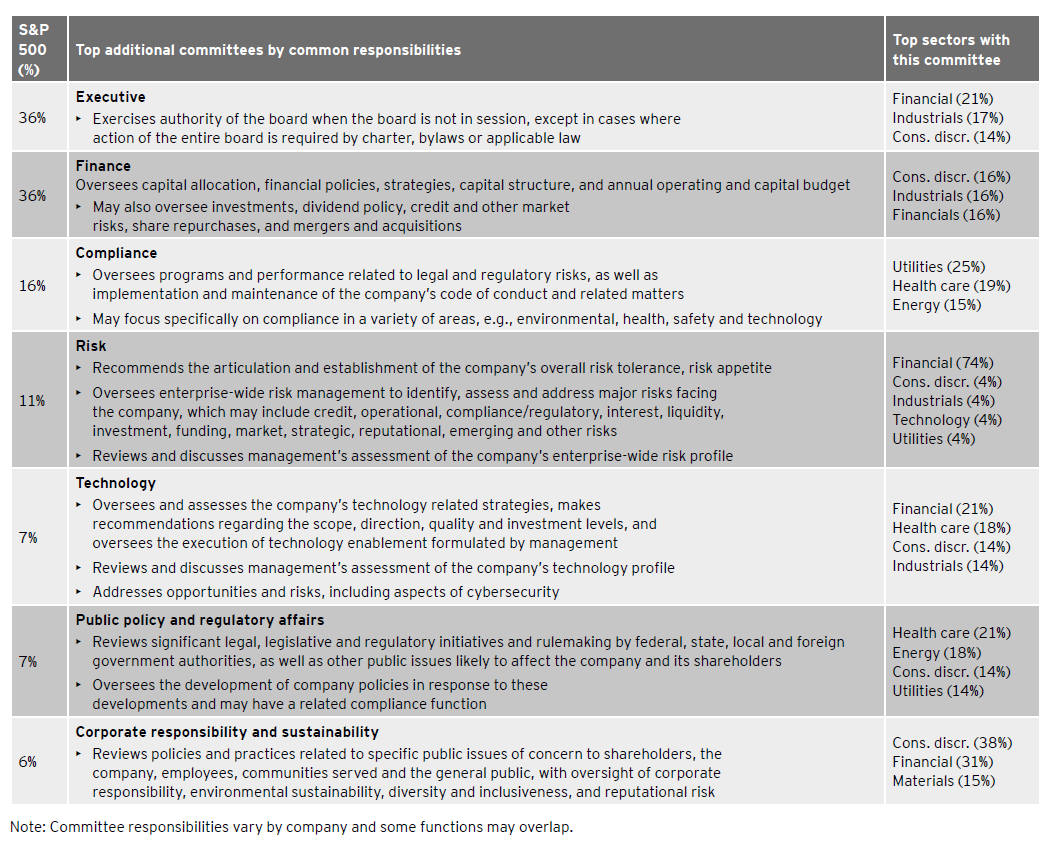

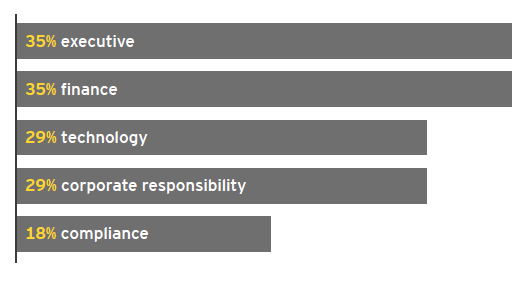

Long-term investors are deeply interested in effective governance and high-quality boards. Shareholders have some agency here as the boards of directors of listed companies are appointed by shareholders. This focus on the board is also a product of the board’s key responsibility as overseer of long-term strategy, although recent work suggests that many public boards neglect this key strategic role and are mired in issues of compliance.

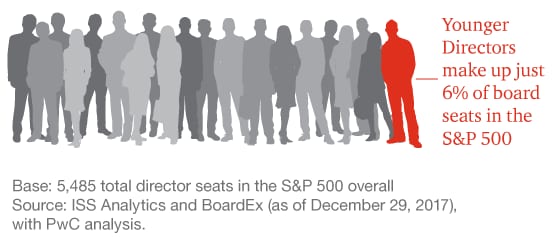

Expectations of the competence and workload of corporate boards have expanded significantly as institutional investors have taken increasingly clear positions on key corporate governance issues such as risk and strategy oversight, entrenchment, pay, tenure, refreshment, and diversity. Investors have also set out broad elements they expect to see in effective corporate governance practices, providing companies with key signals to reflect in their governance arrangements. This more assertive stance is partly driven by a concern that boards have been too passive, unwilling to interrogate the strategy of assertive management teams. Boards have also been identified as a source of short-term performance pressures.

At the CEO Investor Forums, long-term plans are presented by CEOs. Therefore, we ask the CEO to provide commentary on the role of the board (included in our Investor Letter to CEOs). A CEO’s stated understanding of the role expected of the board and its functioning will give investors valuable insights into how effectively a corporation is governed and the extent to which the board is meaningfully involved in strategy formation, oversight and challenge. In a CEO’s discussion of the long-term plan, what is useful is setting out a commentary on the way the board signals for management to take the long-term view—but employ language that isn’t a boilerplate description of formal corporate governance arrangements.

Investor Letter Question: Board’s Involvement in Strategy

How will the composition of your board (today and in the future) help guide the corporation to its long-term strategic goals?

What is the role of the board in setting corporate strategy, setting incentives for and overseeing management?

We note that a useful discussion of the role of the board in corporate strategy, incentives, and oversight could take many forms and that an effective board may have a variety of characteristics beyond a box-tick of observable formal elements.

Omar Ishrak provided an overview of Medtronic’s corporate governance practices. He described a board deeply immersed in the strategy of the business at the business unit level in addition to the overall strategy for the firm (at country-specific and global levels). He indicated that an effort had been made to limit the time spent on compliance issues at the full board level to enable discussion of strategy by business unit and region (which consumed 4-6 hours of every board meeting). Ishrak indicated that these were real, iterative discussions with business unit heads. This is vital commentary as one of the most valuable activities for a board is to debate within itself and with the CEO and senior management the appropriateness and effectiveness of strategy; increasing the likelihood that the board does not take a reflexively subordinate role to CEO and senior management but rather adopts a stance of “constructive support and engaged challenge.”

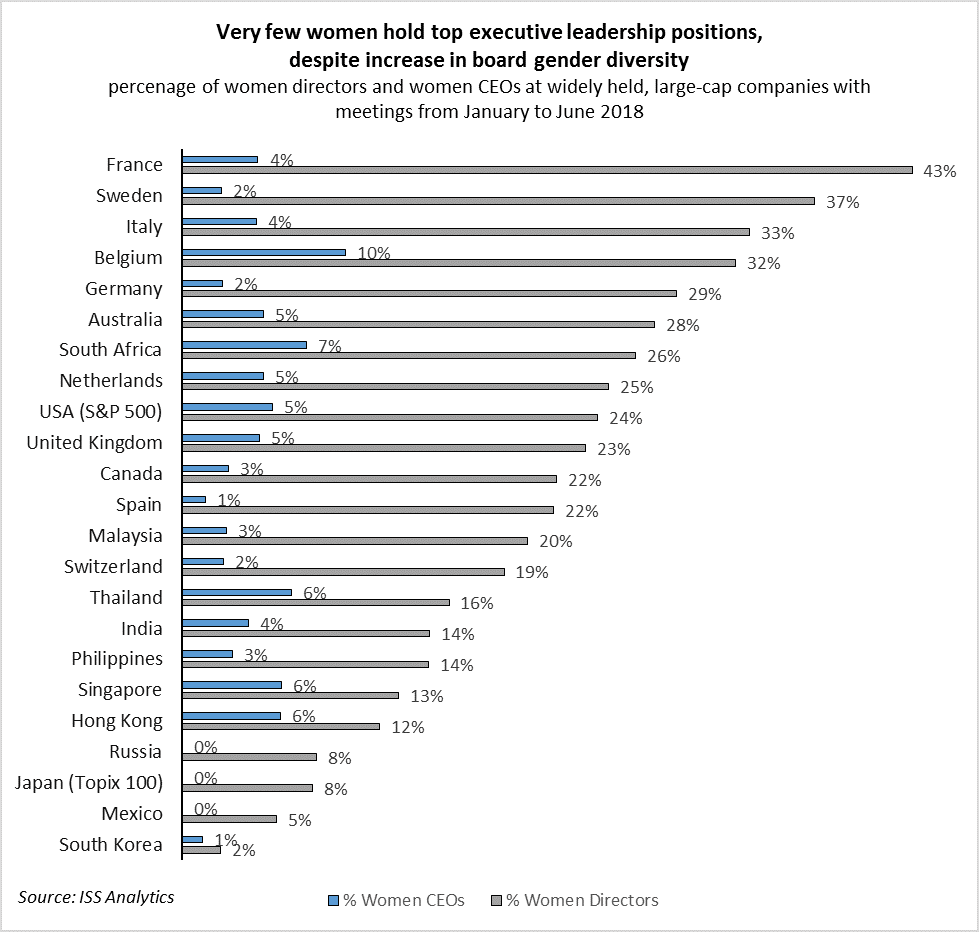

Ishrak talked about the value of diversity within Medtronic’s board and throughout the organization. This complemented similar discussions in the presentations by Ken Frazier (CEO and Chairman of Merck) and Alex Gorsky (CEO and Chairman of Johnson & Johnson) about the need for corporations operating in health care, pharmaceuticals and medical devices to maintain a significant proportion of the board dedicated to professionals with a science background.

Going Further with the Board

Is the board enabled to be effective on long-term strategy:

Investors want to know that boards are performing well and are engaged in meaningful discussions on long-term strategy and related risks. A CEO can spend valuable time explaining the governance structures and procedures the company uses to ensure meaningful strategy discussions:

- Is the full board and relevant board committees structured to facilitate strategy discussion? Is time carved out for strategy discussion?

- Does the board test the assumptions underlying strategy and with what frequency?

- How does the board monitor strategy implementation? Does it seek external views in testing strategy?

- How is the board’s composition, now and in the future, related to long-term strategy?

Insights From FCLTGlobal

FCLTGlobal, a member-supported not-for-profit organization dedicated to developing practical tools that encourage long-term business and investment behaviors, recently published, “Long-term Boards in a Short-term World,” outlining a set of potential tools to aid boards considering taking a longer-term approach.

Directors, as shareholders’ representatives and leaders of the company, typically with average tenures that exceed management, are uniquely positioned to keep a company focused on the distant horizon, setting an appropriate long-term tone for both corporate management and shareholders.

One of the hallmarks of a successful long-term board is direct engagement with long-term shareholders. Companies that have developed board-level relationships with their key shareholders, hearing from them regularly on not just governance topics but also matters related to strategy and investment, benefit from investors’ perspective—lending invaluable insight that serves as a counterpoint to the often short-term views presented by media, the sell-side, and transient or activist investors.

Practical solutions to enable board-level dialogue with shareholders include:

- Appointing a lead independent director or directors as shareholder relationship manager(s),

- Encouraging director attendance and availability for shareholder meetings and at events like investor days, and

- Having a published statement which spells out the Board’s belief of its duty to long-term shareholders.

Capital Allocation

Capital allocation is the fuel that enables strategy implementation—making the investments the strategic plan identifies as key to long-term performance. Corporations strive to maintain enduring capital allocation frameworks. However, these must be adaptable to allow the corporation to make critical long-term investments and capitalize on the competitive landscape, market, and mega-trends it faces.

A long-term plan is an opportunity to highlight those long-term investments that will take time to pay off and perhaps how those investments distinguish the corporation from its industry peers. Investors should be given a working understanding of those investments and be able to track progress against the strategy over time. In Q&A, investors have sought commentary on how CEOs think about capital allocation in the context of the current concerns regarding the extent, timing, and impact of share buy-backs.

Investor Letter Context: Capital Allocation

A corporation should communicate its view of key financially material risks, including long-range mega-trends and the relevant frameworks used to identify ESG factors. The majority of this discussion should focus on the strategy and resources allocated to address future risks.

Investors expect a CEO to outline the corporation’s framework for allocating capital and how that framework enables strategy implementation. CEOs at our Forums have presented such frameworks supplemented by long-range capital distribution goals such as maintaining the historic dividend trajectory.

Vince Forlenza of Becton Dickinson (BD) described how capital allocation and business-relevant stakeholder investments were the keys to the long-term success of his business. Forlenza provided a detailed discussion of the capital allocation framework, with specific dollar allocations to each segment. That set up the discussion of strategy, beginning with BD’s 2020 Sustainability Strategy and Goals—with sustainability discussed as a whole-firm concept. Taking a similar approach, Kevin Clark of Delphi embedded the discussion of capital allocation in the context of the “Safe, Green, and Connected” mega-trends identified earlier. This commentary was well received as it placed the capital allocation framework in the context of core strategy.

Building on These Presentations—The Pozen Framework

Enhancing the discussion of capital allocation through Senior Lecturer, MIT Sloan School of Management Robert Pozen’s capital allocation template:

For the next 3 to 5 years a corporation should outline the target percentage of its annual free cash flow allocated to the following:

Return to shareholders in the form of dividends (and share repurchases); and

Reinvest in the corporation for growth:

How much will be allocated to external growth via acquisitions (or how much will be funded by divestitures), even if this is a qualitative indication?

How much will be allocated to internal growth: i. R&D and innovation? ii. Major capital expenditures? iii. Human capital development? iv. Investments in other capitals or significant stakeholder groups as long-term system-health investments, investments in brand and reputation and in risk mitigation?

Human Capital Management

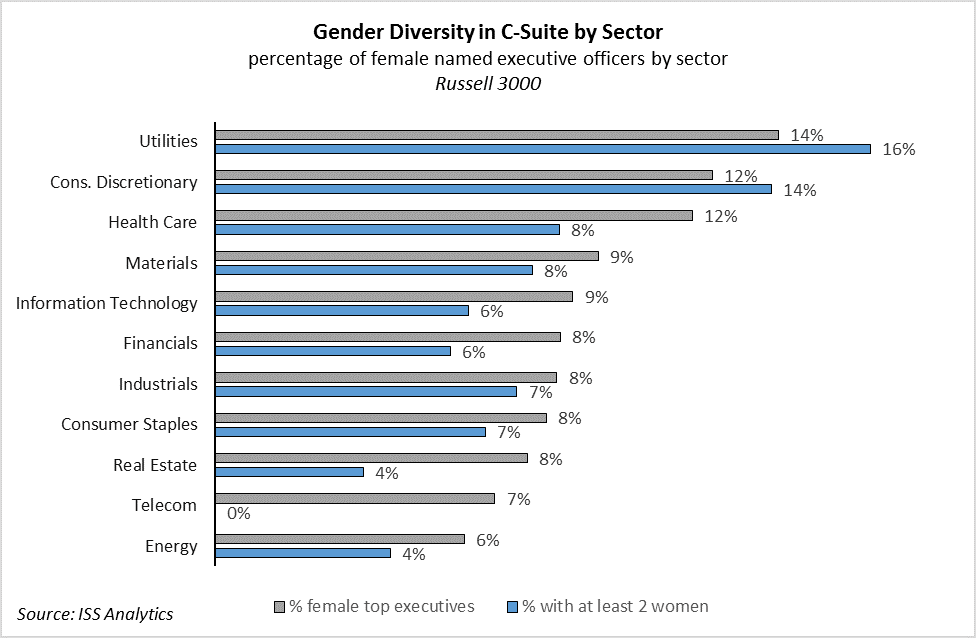

Human capital management is a key source of resilient business performance. As intangibles have become the dominant location of business value, how a business recruits, retains and incentivizes its people has become a value-relevant issue of investor interest.

Human capital management is an extremely broad topic for a CEO to address concisely in a long-term plan as it could include: high-level commentary on establishing and maintaining a strong organizational culture to support the firm’s mission and vision; Occupational Health and Safety compliance; or managing performance on key metrics such as training and development spend, employee turnover and employee engagement survey results. The picture is complicated further by effective human capital management tending not to rely on a single management technique or metric but rather a bundle of supportive practices that work together to drive value.

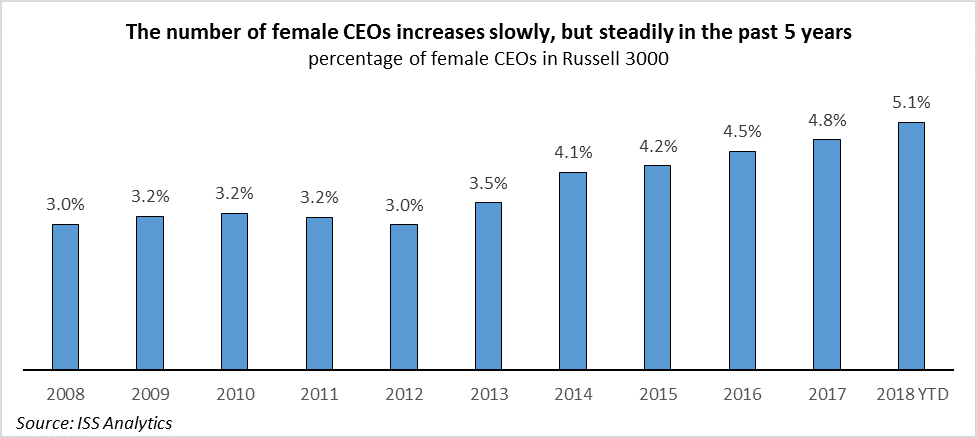

Corporations collect a wealth of human capital metrics for internal management purposes, much of which are not disclosed; regulatory requirements to disclose human capital are very limited.

Investors seek expanded disclosures on human capital. The Human Capital Management Coalition recently submitted a rule-making petition to the SEC to request that the Commission’s required disclosures be extended to include decision-useful information on human capital “policies, practices, and performance”. Investors such as BlackRock and Vanguard have identified human capital as a priority issue in their engagement strategies with investee companies. Index providers, including Thomson Reuters, have developed products (the Diversity & Inclusion Index is one) that acknowledge both the demand for good human capital practices and their value-relevance.

Given the complexity of the issue, a CEO must give priority to telling the corporation’s authentic human capital management story: how is the corporation investing in human capital? how does that relate to long-term strategy? what does the firm expect those investments to achieve in terms of improved performance?

| Human Capital—Financially Material—The Evidence: |

Investor Letter Question: |

- Companies identified as best to work for, outperform

- High-quality human capital management delivers enhanced returns

- Employee engagement correlated with performance

- Human capital analytics enable better performance

|

Human Capital“How do you manage your future human capital requirements over the long term and how do you communicate your future human capital management plans to your investors?” |

A valuable example was provided by Mark Bertolini of Aetna; he spoke about human capital in the context of developing a culture of health for employees, in addition to addressing pay equity, as keys to long-term business performance.

Bertolini identified how employee engagement surveys were uncovering a pattern of employees talking about the difficulties of their working lives. These lower-income employees tended to be on food stamps and Medicaid. Bertolini explained his decision to raise wages and reduce the health care costs of these workers. He then identified key costs and outcomes: $27 million cost in year one, 5,700 workers affected, on average 22% increase in disposable income. This initiative was combined with programs on mindfulness, tuition assistance, and life style practices associated with productivity (e.g., paying employees to get 8 hours of sleep a night). Bertolini indicated that these measures were associated with significant increases in employee engagement scores—but he emphasized that it was vital for management to “get beyond the spreadsheet” to understand the benefits (hard and soft) of such investments in human capital over the long term. This commentary provides investors with an understanding of management’s view of the business and some of its thinking about its people and how that relates to the operating performance and financial prospects of the business.

Meeting Investor Needs on Human Capital

Human capital is a material issue across industries, though the relevance of human capital-related factors can vary by sector. Investors have identified a variety of measures by which corporations can enhance their disclosure of human capital issues.

Nine broad categories of information were deemed fundamental to human capital analysis as a starting point to ongoing dialogue with investors:

| Workforce demographics |

Workforce stability |

Workforce composition |

| Workforce skills and capabilities |

Workforce culture and empowerment |

Workforce health and safety |

| Workforce productivity |

Human rights |

Workforce compensation and incentives |

Shareholder and Stakeholder Engagement

Shareholder expectations of the volume and quality of engagement with investee companies have expanded significantly. The Commonsense Corporate Governance Principles regard effective corporate governance as requiring constructive engagement between a company and its shareholders. This is reflected in companies taking more time to prepare directors for on-going engagements and relationship building with investors and devoting significant time and resources to such engagements. Investors use these year-round engagements to inform their investing outlook, voting, and future engagement activities—and expect companies to be responsive, to some extent, to these engagements.

Shareholders expect investee companies to develop a rigorous process and framework for managing shareholder engagement and responding to the themes on which meaningful investor engagement takes place. Corporations can take several approaches. However, it is key that they enable their shareholders to understand the approach and structure of investor engagement efforts—this allows investors to respond and coordinate their activities accordingly.

A long-term plan also gives a CEO an opportunity to reflect on the company’s relationship with its broader community of stakeholders. As a long-term plan is an investor-facing presentation, it is useful for a CEO to highlight the framework through which the corporation identifies which stakeholder interests are critical to the long-term success of the company and how the corporation seeks to manage those stakeholder relationships.

Investor Letter Question: Shareholder and Stakeholder Engagement

What is the corporation’s framework/strategies for interacting with its shareholders and key stakeholders?

Prudential’s presentation by Marc Grier, Chairman of the Board, outlined a set of leading corporate governance practices that it has adopted, including designating its Lead Independent Director as the primary point of engagement with shareholders. Prudential had also sought to describe its approach to shareholder engagement, quantify such engagement, and account for its outcomes in expanded proxy statement disclosures (identified as an example of best practice by the Council of Institutional Investors).

Corporations have taken different approaches to identifying key stakeholder interests and describing the business, strategy and governance implications of that effort. Merck’s CEO Ken Frazier described a stakeholder matrix in which more than 40 stakeholder issues were analyzed in the context of long-term business performance. Frazier identified how that matrix helped inform board-level strategy considerations—and had proved useful in guiding the long-term direction of the company.

Telia CEO Johan Dennelind explained how its board of directors had adopted a statement of significant audiences and materiality. Through this kind of statement, a board acknowledges a specific set of stakeholders (broader than shareholders) relevant to its future success and key material issues for its business. The statement is a new tool on the corporate reporting landscape. In addition to the benefits it offers a board in thinking through key issues and stakeholders, such a statement may help CEOs provide investors with an overview of how the corporation thinks about and manages material stakeholder interests.

Récemment, un ami qui prépare une conférence sur la gouvernance des coopératives me demanda si je pouvais lui procurer des références sur les spécificités de ce type d’organisation pour les administrateurs d’un CA en relation avec d’autres catégories d’entreprises.

J’ai réalisé que je n’avais pas beaucoup publié sur les coopératives comme mode d’organisation du travail. Le portail du gouvernement du Québec sur les coopératives est une mine d’informations très pertinentes pour toutes les questions concernant les coopératives. Les articles suivants sont importants pour bien définir le contexte :

Définition d’une coopérative

Gouvernance des coopératives

On y note que celles-ci constituent une grande part de l’économie québécoise et qu’elles sont présentes dans de nombreux secteurs d’activité économique.