Le Bureau de la vérification interne (BVI) de l’Université de Montréal (UdeM) a récemment développé un cadre de référence novateur pour l’évaluation de la gouvernance. La méthodologie, ainsi que le questionnaire qui en résulte, contribue, à mon avis, à l’avancement des connaissances dans le domaine de l’évaluation des caractéristiques et des pratiques de la gouvernance par les auditeurs internes.

Ayant eu l’occasion de collaborer à la conception de cet instrument de mesure de la gouvernance des sociétés, j’ai obtenu du BVI la permission de publier le résultat de cet exercice.

Cette version du cadre se veut « générique » et peut être utilisée pour l’évaluation de la gouvernance d’un projet, d’une activité, d’une unité ou d’une entité.

De ce fait, les termes, les intervenants ainsi que les structures attendues doivent être adaptés au contexte de l’évaluation. Il est à noter que ce cadre de référence correspond à une application optimale recherchée en matière de gouvernance. Certaines pratiques pourraient ne pas s’appliquer ou ne pas être retenues de façon consciente et transparente par l’organisation.

Le questionnaire se décline en dix thèmes, chacun comportant dix items :

Thème 1 — Structure et fonctionnement du Conseil

Thème 2 — Travail du président du Conseil

Thème 3 — Relation entre le Conseil et le directeur général (direction)

Thème 4 — Structure et travail des comités du Conseil

Thème 5 — Performance du Conseil et de ses comités

Thème 6 — Recrutement, rémunération et évaluation du rendement du directeur général

Thème 7 — Planification stratégique

Thème 8 — Performance et reddition de comptes

Thème 9 — Gestion des risques

Thème 10 — Éthique et culture organisationnelle

On retrouvera en Annexe une représentation graphique du cadre conceptuel qui permet d’illustrer les liens entre les thèmes à évaluer dans le présent référentiel.

L’évaluation s’effectue à l’aide d’un questionnaire de type Likert (document distinct du cadre de référence). L’échelle de Likert est une échelle de jugement par laquelle la personne interrogée exprime son degré d’accord ou de désaccord eu égard à une affirmation ou une question.

- Tout à fait d’accord

- D’accord

- Ni en désaccord ni d’accord

- Pas d’accord

- Pas du tout d’accord

- Ne s’applique pas (S.O.)

Une section commentaire est également incluse dans le questionnaire afin que les participants puissent exprimer des informations spécifiques à la question. L’audit interne doit réaliser son évaluation à l’aide de questionnaires ainsi que sur la base de la documentation qui lui sera fournie.

Thème 1 — Structure et fonctionnement du Conseil

(Questions destinées au président du comité de gouvernance [PCG] et/ou au président du Conseil [PC])

| 1. Le Conseil compte-t-il une proportion suffisante de membres indépendants pour lui permettre d’interagir de manière constructive avec la direction ? |

| 2. La taille du Conseil vous semble-t-elle raisonnable compte tenu des objectifs et de la charge de travail actuel ? (dans une fourchette idéale de 9 à 13 membres, avec une moyenne d’environ 10 membres) |

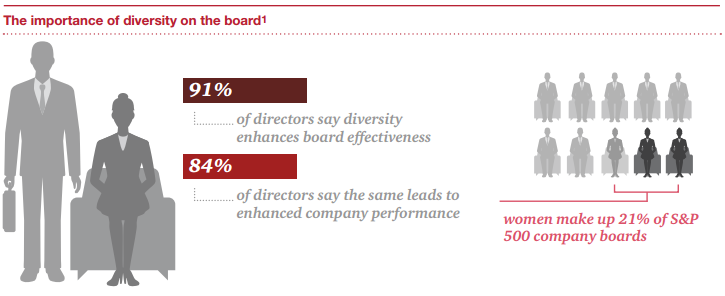

| 3. La composition du Conseil est-elle guidée par une politique sur la diversité des membres ? |

| 4. Le Conseil a-t-il conçu un processus rigoureux de recrutement de ses membres, basé sur une matrice des compétences complémentaires ? |

| 5. Le président et les membres du comité responsable du recrutement (comité de gouvernance) ont-ils clairement exprimé aux candidats potentiels les attentes de l’organisation en matière de temps, d’engagement et de contributions reliés avec leurs compétences ? |

| 6. Les réunions sont-elles bien organisées et structurées ? (durée, PV, taux de présence, documentation pertinente et à temps, etc.) |

| 7. Les échanges portent-ils sur surtout sur des questions stratégiques, sans porter sur les activités courantes (qui sont davantage du ressort de l’équipe de direction) ? |

| 8. Les membres sont-ils à l’aise d’émettre des propos qui vont à contre-courant des idées dominantes ? |

| 9. Une séance à huis clos est-elle systématiquement prévue à la fin de chacune des réunions afin de permettre aux membres indépendants de discuter des sujets sensibles ? |

| 10. Les membres ont-ils accès à la planification des rencontres sur une période idéale de 18 mois en y incluant certains items ou sujets récurrents qui seront abordés lors des réunions du Conseil (plan de travail) ? |

Thème 2 — Travail du président du Conseil

(Questions destinées à un administrateur indépendant, au PC [auto-évaluation] et au président du comité de gouvernance [PCG])

| 1. Le président s’assure-t-il de former un solide tandem avec le directeur général et de partager avec lui une vision commune de l’organisation ? |

| 2. Le président promeut-il de hauts standards d’efficacité et d’intégrité afin de donner le ton à l’ensemble de l’organisation ? |

| 3. Le président, de concert avec le directeur général, prépare-t-il adéquatement les réunions du Conseil ? |

| 4. Le président préside-t-il avec compétence et doigté les réunions du Conseil ? |

| 5. Le président s’assure-t-il que les échanges portent surtout sur des questions stratégiques et que les réunions du Conseil ne versent pas dans la micro gestion ? |

| 6. Le président s’investit-il pleinement dans la sélection des présidents et des membres des comités du Conseil ? |

| 7. Le président s’assure-t-il de l’existence d’une formation et d’une trousse d’accueil destinées aux nouveaux membres afin qu’ils soient opérationnels dans les plus brefs délais ? |

| 8. Le président s’assure-t-il de l’existence d’un processus d’évaluation du rendement du Conseil et de ses membres ? |

| 9. Le président prend-il la peine d’aborder les membres non performants pour les aider à trouver des solutions ? |

| 10. Le président s’assure-t-il que les membres comprennent bien leurs devoirs de fiduciaire, c’est-à-dire qu’ils doivent veiller aux meilleurs intérêts de l’organisation et non aux intérêts de la base dont ils sont issus ? |

Thème 3 — Relation entre le Conseil et le directeur général (direction)

(Questions destinées au PC et au Directeur général [DG])

| 1. Le président du Conseil et le directeur général ont-ils des rencontres régulières et statutaires pour faire le point entre les réunions du Conseil ? |

| 2. Le président du Conseil et le directeur général maintiennent-ils une communication franche et ouverte ? (équilibre entre une saine tension et des relations harmonieuses et efficaces) |

| 3. Le Conseil résiste-t-il à la tentation de faire de la micro gestion lors de ses réunions et s’en tient-il à assumer les responsabilités qui lui incombent ? |

| 4. Le Conseil agit-il de façon respectueuse à l’endroit du directeur général lors des réunions du Conseil et cherche-t-il à l’aider à réussir ? |

| 5. Le Conseil procède-t-il à une évaluation annuelle du rendement du directeur général (par le comité de GRH) basée sur des critères objectifs et mutuellement acceptés ? |

| 6. Les membres du Conseil s’abstiennent-ils de donner des ordres ou des directives aux employés qui relèvent de l’autorité du directeur général ? |

| 7. Le président comprend-il que le directeur général ne relève pas de lui, mais plutôt du Conseil, et agit-il en conséquence ? |

| 8. Le directeur général aide-t-il adéquatement le président dans la préparation des réunions du Conseil, fournit-il aux membres l’information dont ils ont besoin et répond-il à leurs questions de manière satisfaisante ? |

| 9. Le directeur général s’assure-t-il de ne pas embourber les réunions du Conseil de sujets qui relèvent de sa propre compétence ? |

| 10. Le directeur général accepte-t-il de se rallier aux décisions prises par le Conseil, même dans les cas où il a exprimé des réserves ? |

Thème 4 — Structure et travail des comités du Conseil

(Questions destinées au PC et au président d’un des comités)

| 1. Existe-t-il, au sein de votre organisation, les comités du Conseil suivants :

· Audit ? · Gouvernance ? · Ressources humaines ? · Gestion des risques ? · Sinon, a-t-on inclus les responsabilités de ces comités dans le mandat du Conseil ou d’une autre instance indépendante ? · Autres comités reliés à la recherche (ex. éthique, scientifique) ?

|

| 2. Les recommandations des comités du Conseil aident-elles le Conseil à bien s’acquitter de son rôle ? |

| 3. Les comités du Conseil sont-ils actifs et présentent-ils régulièrement des rapports au Conseil ? |

| 4. Estimez-vous que les comités créent de la valeur pour votre organisation ? |

| 5. Les comités du Conseil s’abstiennent-ils de s’immiscer dans la sphère de responsabilité du directeur général ? |

| 6. À l’heure actuelle, la séparation des rôles et responsabilités respectifs du Conseil, des comités et de la direction est-elle officiellement documentée, généralement comprise et mise en pratique ? |

| 7. Les membres qui siègent à un comité opérationnel comprennent-ils qu’ils travaillent sous l’autorité du directeur général ? |

| 8. Le directeur général est-il invité à assister aux réunions des comités du Conseil ? |

| 9. Chacun des comités et des groupes de travail du Conseil dispose-t-il d’un mandat clair et formulé par écrit ? |

| 10. S’il existe un comité exécutif dans votre organisation, son existence est-elle prévue dans le règlement de régie interne et, si oui, son rôle est-il clairement défini ? |

Thème 5 — Performance du Conseil et de ses comités

(Questions destinées au PC et au président du comité de gouvernance [PCG])

| 1. Est-ce que la rémunération des membres du Conseil a été déterminée par le comité de gouvernance ou avec l’aide d’un processus indépendant ? (Jetons de présence ?) |

| 2. Par quels processus s’assure-t-on que le Conseil consacre suffisamment de temps et d’attention aux tendances émergentes et à la prévision des besoins futurs de la collectivité qu’il sert ? |

| 3. Est-ce que l’on procède à l’évaluation de la performance du Conseil, des comités et de ses membres au moins annuellement ? |

| 4. Est-ce que la logique et la démarche d’évaluation ont été expliquées aux membres du Conseil, et ceux-ci ont-ils pu donner leur point de vue avant de procéder à l’évaluation ? |

| 5. A-t-on convenu préalablement de la façon dont les données seront gérées de manière à fournir une garantie sur la confidentialité de l’information recueillie ? |

| 6. Est-ce que le président de Conseil croit que le directeur général et la haute direction font une évaluation positive de l’apport des membres du Conseil ? |

| 7. L’évaluation du Conseil et de ses comités mène-t-elle à un plan d’action réaliste pour prendre les mesures nécessaires selon leur priorité ? |

| 8. L’évaluation du Conseil permet-elle de relever les lacunes en matière de compétences et d’expérience qui pourraient être comblées par l’ajout de nouveaux membres ? |

| 9. Est-ce que les membres sont évalués en fonction des compétences et connaissances qu’ils sont censés apporter au Conseil ? |

| 10. Les membres sont-ils informés par le président du Conseil de leurs résultats d’évaluation dans le but d’aboutir à des mesures de perfectionnement ? |

Thème 6 — Recrutement, rémunération et évaluation du rendement du DG

(Questions destinées au PC, au DG [auto-évaluation] et au président du comité des RH)

| 1. Existe-t-il une description du poste de directeur général ? Cette description a-t-elle servi au moment de l’embauche du titulaire du poste ? |

| 2. Un comité du Conseil (comité de GRH) ou un groupe de membres indépendants est-il responsable de l’évaluation du rendement du directeur général (basé sur des critères objectifs) ? |

| 3. Le président du Conseil s’est-il vu confier un rôle prépondérant au sein du comité responsable de l’évaluation du rendement du directeur général afin qu’il exerce le leadership que l’on attend de lui ? |

| 4. Le comité responsable de l’évaluation du rendement et le directeur général ont-ils convenu d’objectifs de performance sur lesquels ce dernier sera évalué ? |

| 5. Le rendement du directeur général est-il évalué au moins une fois l’an en fonction de ces objectifs ? |

| 6. Les objectifs de rendement du directeur général sont-ils liés au plan stratégique ? |

| 7. Le comité responsable de l’évaluation du rendement s’est-il entretenu avec le directeur général en cours d’année pour lui donner une rétroaction préliminaire ? |

| 8. La rémunération du directeur général est-elle équitable par rapport à l’ensemble des employés et a-t-elle fait l’objet d’une analyse comparative avec le marché des organisations afin d’assurer un certain degré de compétitivité ? |

| 9. Les hausses salariales du directeur général sont-elles uniquement accordées en fonction de l’évaluation de son rendement ? |

| 10. Est-ce que le Conseil consacre l’attention nécessaire à la succession du directeur général et dispose-t-il d’un processus robuste d’identification d’un nouveau premier dirigeant, tant pour les transitions planifiées que non planifiées ? |

Thème 7 — Planification stratégique

(Questions destinées au PC et au DG)

| 1. Votre organisation possède-t-elle un plan stratégique incluant notamment :

· le contexte dans lequel évoluent la société et les principaux enjeux auxquels elle fait face ? · les objectifs et les orientations stratégiques de la société ? · les résultats visés au terme de la période couverte par le plan ? · les indicateurs de performance utilisés pour mesurer l’atteinte des résultats ? |

| 2. Le plan stratégique porte-t-il sur une période cohérente avec la mission et l’environnement dans lequel il œuvre ? |

| 3. La mission, les valeurs et l’énoncé de vision de l’organisation ont-ils été déterminés et réévalués périodiquement ? |

| 4. Est-ce qu’il y a eu une analyse Forces/faiblesses et opportunités/menaces ? |

| 5. L’ensemble des parties prenantes de l’organisation a-t-il été consulté notamment au moyen de sondages et d’entrevues, et lors d’un atelier de planification stratégique ? |

| 6. Les membres ont-ils été engagés dans le processus, notamment par la création d’un comité ad hoc chargé de piloter l’exercice et par des rapports périodiques aux réunions du Conseil ? |

| 7. Le Conseil évalue-t-il la stratégie proposée, notamment les hypothèses clés, les principaux risques, les ressources nécessaires et les résultats cibles, et s’assure-t-il qu’il traite les questions primordiales telles que l’émergence de la concurrence et l’évolution des préférences des clients ? |

| 8. Le président du Conseil s’assure-t-il que le plan stratégique soit débattu lors de réunions spéciales et que le Conseil dispose de suffisamment de temps pour être efficace ? |

| 9. Le Conseil est-il satisfait des plans de la direction pour la mise en œuvre de la stratégie approuvée ? |

| 10. Le Conseil surveille-t-il la viabilité permanente de la stratégie, et est-elle ajustée, si nécessaire, pour répondre aux évolutions de l’environnement ? |

Thème 8 — Performance et reddition de comptes

(Questions destinées au Président du comité d’audit ou au PC, au DG et au secrétaire corporatif)

| 1. S’assure-t-on que les indicateurs de performance utilisés par la direction et présentés au Conseil sont reliés à la stratégie de l’organisation et aux objectifs à atteindre ? |

| 2. S’assure-t-on que les indicateurs de la performance sont équilibrés entre indicateurs financiers et non financiers, qu’ils comprennent des indicateurs prévisionnels et permettent une comparaison des activités similaires ? |

| 3. A-t-on une assurance raisonnable de la fiabilité des indicateurs de performance qui sont soumis au Conseil ? |

| 4. Utilise-t-on des informations de sources externes afin de mieux évaluer la performance de l’organisation ? |

| 5. Le Conseil et les comités réexaminent-ils régulièrement la pertinence de l’information qu’il reçoit ? |

| 6. Le Conseil examine-t-il d’un œil critique les informations à fournir aux parties prenantes ? |

| 7. Le Conseil est-il satisfait du processus de communication de crise de la société et est-il à même de surveiller de près son efficacité si une crise survient ? |

| 8. Le Conseil est-il satisfait de son implication actuelle dans la communication avec les parties prenantes externes et comprend-il les évolutions susceptibles de l’inciter à modifier son degré de participation ? |

| 9. Est-ce que la direction transmet suffisamment d’information opérationnelle au Conseil afin que celui-ci puisse bien s’acquitter de ses responsabilités de surveillance ? |

| 10. Est-ce que le Conseil s’assure que les informations sont fournies aux parties prenantes telles que les organismes réglementaires, les organismes subventionnaires et les partenaires d’affaires ? |

Thème 9 — Gestion des risques

(Questions destinées au PC et au Président du comité de Gestion des risques ou au Président du comité d’audit)

| 1. L’organisation a-t-elle une politique de gestion des risques et obtient-elle l’adhésion de l’ensemble des dirigeants et des employés ? |

| 2. L’organisation a-t-elle identifié et évalué les principaux risques susceptibles de menacer sa réputation, son intégrité, ses programmes et sa pérennité ainsi que les principaux mécanismes d’atténuation ? |

| 3. L’organisation a-t-elle un plan de gestion de la continuité advenant un sinistre ? |

| 4. Est-ce que les risques les plus élevés font l’objet de mandats d’audit interne afin de donner un niveau d’assurance suffisant aux membres du Conseil ? |

| 5. L’organisation se penche-t-elle occasionnellement sur les processus de contrôle des transactions, par exemple l’autorisation des dépenses, l’achat de biens et services, la vérification et l’approbation des factures et des frais de déplacement, l’émission des paiements, etc. ? |

| 6. Existe-t-il une délégation d’autorité documentée et comprise par tous les intervenants ? |

| 7. Le Conseil a-t-il convenu avec la direction de l’appétit pour le risque ? (le niveau de risque que l’organisation est prête à assumer) |

| 8. Le Conseil est-il informé en temps utile lors de la matérialisation d’un risque critique et s’assure-t-il que la direction les gère convenablement ? |

| 9. S’assure-t-on que la direction entretient une culture qui encourage l’identification et la gestion des risques ? |

| 10. Le Conseil s’est-il assuré que la direction a pris les mesures nécessaires pour se prémunir des risques émergents, notamment ceux reliés à la cybersécurité et aux cyberattaques ? |

Thème 10 — Éthique et culture organisationnelle

(Questions destinées au DG et au PC)

| 1. Les politiques de votre organisation visant à favoriser l’éthique sont-elles bien connues et appliquées par ses employés, partenaires et bénévoles ? |

| 2. Le Conseil de votre organisation aborde-t-il régulièrement la question de l’éthique, notamment en recevant des rapports sur les plaintes, les dénonciations ? |

| 3. Le Conseil et l’équipe de direction de votre organisation participent-ils régulièrement à des activités de formation visant à parfaire leurs connaissances et leurs compétences en matière d’éthique ? |

| 4. S’assure-t-on que la direction générale est exemplaire et a développé une culture fondée sur des valeurs qui se déclinent dans l’ensemble de l’organisation ? |

| 5. S’assure-t-on que la direction prend au sérieux les manquements à l’éthique et les gère promptement et de façon cohérente ? |

| 6. S’assure-t-on que la direction a élaboré un code de conduite efficace auquel elle adhère, et veille à ce que tous les membres du personnel en comprennent la teneur, la pertinence et l’importance ? |

| 7. S’assure-t-on de l’existence de canaux de communication efficaces (ligne d’alerte téléphonique dédiée, assistance téléphonique, etc.) pour permettre aux membres du personnel et partenaires de signaler les problèmes ? |

| 8. Le Conseil reconnaît-il l’impact sur la réputation de l’organisation du comportement de ses principaux fournisseurs et autres partenaires ? |

| 9. Est-ce que le président du Conseil donne le ton au même titre que le DG au niveau des opérations sur la culture organisationnelle au nom de ses croyances, son attitude et ses valeurs ? |

| 10. Est-ce que l’organisation a la capacité d’intégrer des changements à même ses processus, outils ou comportements dans un délai raisonnable ? |

Annexe

Présentation du schéma conceptuel

Thème (1) — Structure et fonctionnement du Conseil

Thème (2) — Travail du président du Conseil

Thème (3) — Relation entre le Conseil et le directeur général (direction)

Thème (4) — Structure et travail des comités du Conseil

Thème (5) — Performance du Conseil et de ses comités

Thème (6) — Recrutement, rémunération et évaluation du rendement du directeur général

Thème (7) — Planification stratégique

Thème (8) — Performance et reddition de comptes

Thème (9) — Gestion des risques

Thème (10) — Éthique et culture organisationnelle

L’article donne également l’exemple du comportement de l’entreprise eBay en ce qui a trait à la divulgation détaillée de son approche à la succession des dirigeants dans la circulaire à l’intention des actionnaires.

L’article donne également l’exemple du comportement de l’entreprise eBay en ce qui a trait à la divulgation détaillée de son approche à la succession des dirigeants dans la circulaire à l’intention des actionnaires.